For 50 years, Irving Schild proudly belonged to a “usual gang of idiots” who reveled in skewering sacred cows and poking proverbial fingers in the eyes of the powerful.

Schild, 88, who has a summer house at Lake Wallenpaupack, was a photographer for MAD Magazine from 1965 to 2017.

Symbolized by gap-toothed, jug-eared mascot Alfred E. Neuman and his “What — me worry?” slogan, the legendary satire magazine recently announced it would cease publication of new material after its August issue, ending a 67-year run.

Schild’s last photo for the magazine appeared in a parody ad on the back cover of the June 2017 issue. In an interview last week at his lake house, Schild reflected on being part of a cultural institution that influenced generations of Americans, ranging from National Lampoon and “Saturday Night Live” to “Weird Al” Yankovic and “The Simpsons” writers.

“It’s the end of a great club,” Schild said of the artists and contributors self-mockingly labeled in the magazine’s table of contents as the usual gang of idiots. “It was a great club. The beauty to be with these people, all geniuses, the best in America. Unbelievable.”

America via Belgium

His journey to becoming a MAD man is an improbable, “only in America” tale, he said.

His story began in Belgium, where he was born in 1931. Schild was a young boy when his Jewish family fled Nazi Germany during the beginning of World War II. Kristallnacht, the night of Nov. 9 and 10, 1938, when Nazis attacked Jewish people and property in Germany, really scared Schild’s father.

“Anti-Semitism was rampant in Belgium,” Schild recalled. “(My father) said as soon as the first bomb falls in Belgium, we are going to go to France.”

When the Nazis hit Brussels, the Schilds fled on a train to France. They were interned in France until they paid off a guard to let them escape. They fled to the Italian Alps, where they hid out in the mountains, eventually making their way to Rome.

Schild’s grandparents perished at Auschwitz.

The Schilds were in Rome when the war in Europe ended.

“When we got liberated in Rome, my father stood at the Colosseum and drew the liberators — the GIs, the British, the Americans, the Australians — for a buck. A drawing with the Colosseum in the back,” Schild said. “I inherited his (artistic) talent.”

JASON FARMER / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Irving Schild, 88, who was photographer for MAD Magazine for 50 years, digs through samples of his work.

Post-war years

His family then became part of a group of more than 900 Holocaust and war refugees accepted by the Roosevelt administration for resettling in the United States, in Oswego, New York.

Wanting to be an artist, Schild was accepted to study at New York’s celebrated Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

But while enrolled there, Schild was drafted into the Marine Corps. The Marines sent him to a military photography school, where he learned the artform from the ground up. He served two years of active duty and six years of inactive duty and became an American citizen during his service.

Schild returned to Cooper to finish his studies. Afterward, he became an artist in New York City, working first in art design and advertising and later as a photographer. Schild taught photography at Fashion Institute of Technology and served as chairman of its photography department, while also working as a freelance photographer. His work has appeared in Life, Glamour and Esquire magazines, among others.

MAD men

During the ’60s, while frequenting a coffee shop in Manhattan near his studio, Schild struck up a rapport with another patron there, a gregarious Spaniard with a handlebar mustache.

Sergio Aragones was an artist for MAD Magazine, which also had offices nearby. Famed for his microscopic, wordless “Marginal Thinking” cartoon vignettes appearing sporadically in the margins of the pages of MAD, Aragones suggested that Schild come work for the magazine, Schild recalled.

MAD was founded in 1952 by Brooklyn-born comics publisher William Gaines, whose father ranked among earlier pioneers of the comics industry. A rumpled, outsized character in his own right, Gaines, who died in 1992, fostered an unorthodox environment at MAD for staff to create and control the magazine’s biting content.

Gaines also was loyal to his staff, and vice versa. He used to take the MAD crew on annual trips, for a week at a time, to locales all over the globe. The jaunts were part reward and part enrichment.

“He wanted the magazine to be worldly,” Schild said of the annual trips. “He wanted his artists that never traveled — most of them did travel, some did not — he wanted them to see the world: Japan, China, Rome, Paris, London,” to name a few destinations.

One of MAD’s early editors, Albert Feldstein, also had a big impact on Schild and his work. Feldstein insisted Schild use a large, heavy camera that required a tripod for producing images akin to those in Life magazine.

Schild loved working for MAD and viewed each assignment as a problem to solve. He had to figure out how to create a photographic image that would illustrate the joke at hand.

“MAD was a real challenge. They considered me also an artist, and I came from art. That’s why I was able to answer their challenges,” Schild said. “I love challenges. I love (solving) problems.”

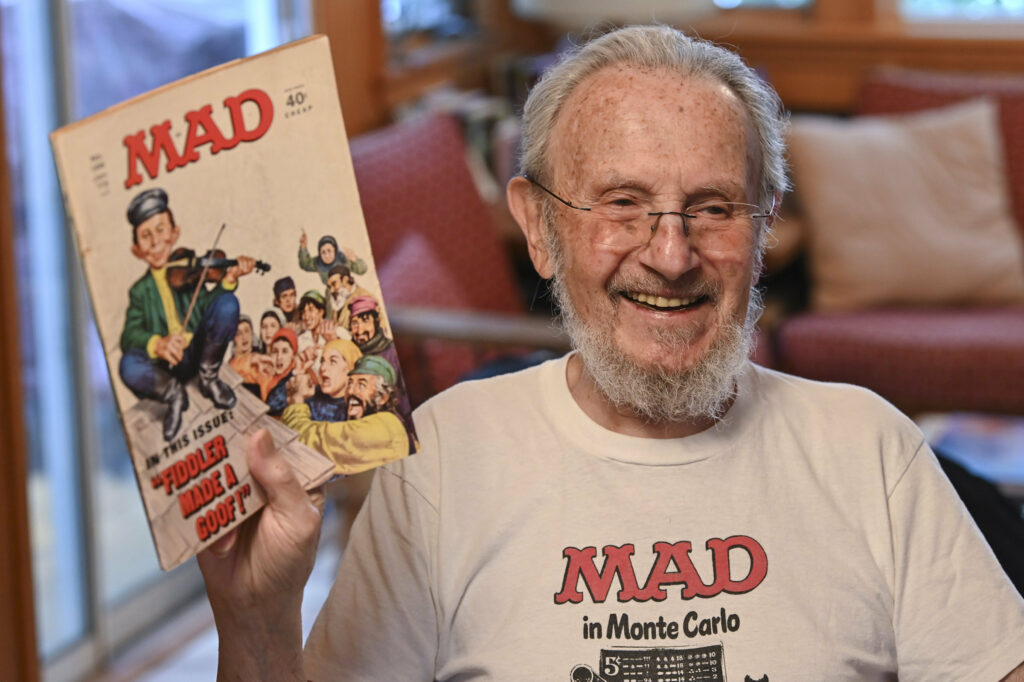

JASON FARMER / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Irving Schild, 88, was photographer for MAD Magazine for 50 years as he holds one of his favorite pieces of work.

Friends join in the fun

Schild also preferred, if possible, to feature friends and fellow MAD staffers as subjects in his photo shoots.

Members of the Roos family of Honesdale, longtime friends of Schild, were featured several times over the years, said Paula Roos.

“We posed for a lot of things,” Roos said. “They needed a takeoff on ‘The Brady Brunch’ for an annual special. We were the Brady Bunch. I was Mrs. Brady. We used to have a lot of fun” during the shoots.

For a parody ad poking fun at the National Rifle Association, Schild photographed a whitetail deer in the woods at Lake Wallenpaupack. The image then was doctored to put fluorescent orange hunting clothing on the deer, standing upright and holding a rifle under the words “I’m the NRA,” — except in this case, NRA stood for Nature’s Revenge Association.

Schild’s favorite of his MAD photos was published as a glossy color mini-poster that dumped on Nazism — a roll of toilet paper with a swastika pattern under the words, “Wipe Out Hate!”

“This stands up much more today than even then,” Schild said, referring to the photo as a statement against anti-Semitism, which he sees as on the rise again.

Another favorite photo of Schild’s featured on a back cover of MAD after the Nixon pardon featured a man posing as Der Führer and the words, “… So Why Not … Pardon Hitler!”

What — him worry?

In recent years, Schild could see MAD’s end on the horizon, presaged by declining circulation and various changes that had been afoot.

“I didn’t think the magazine was going to continue the way they were doing it,” he said.

Schild still enjoys taking photos and solving problems to compose images. He marvels at how modern digital and computer technology have transformed the craft and art. He has replaced the darkroom and developing process with modern computers and Photoshop, which he taught himself to use. He recently sold off thousands of dollars of obsolete cameras and equipment.

Schild also occasionally speaks to groups and organizations about his life story of surviving the war and living the American dream.

“Lucky to be here,” Schild said.

Contact the writer: jlockwood@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5185; @jlockwoodTT on Twitter

Caitlin Heaney West is the content editor for Access NEPA and oversees the Early Access blog in addition to working as a copy editor and staff writer for The Times-Tribune. An award-winning journalist, she is a summa cum laude graduate of Shippensburg University and also earned a master’s degree from Marywood University. Caitlin joined the Times-Shamrock family in 2009 and lives in Scranton. Contact: cwest@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5107; or @cheaneywest