I’m going to paraphrase part of Jerry Seinfeld’s speech at the Baseball Writers Association of America banquet in New York City from last week, because I used to think it was a great quote and now I think it’s the truest thing I’ve ever heard: In this world, we have two things, real life and sports. And, one helps you get through the other.

Honestly, I don’t know where Kobe Bryant falls on that spectrum, and God knows I’ve had enough time to think about it. It takes a lot to stun those of us who’ve been in the sports reporting business for a long-enough time. You expect the unexpected. You see the worst in people you were convinced were good, and you see the best in people you were convinced fell short of good. All the time.

And then a day like Sunday comes along. My wife and I took our morning walk. We cleared some brush that fell into the yard after a bit of a windstorm the night before. We went inside and made BLTs for lunch. We sat down to watch a show. Typical Sunday, until I got a text message from my good friend Darren Headrick, the talented play by play voice of the Kentucky women’s basketball and baseball teams who became close as a brother during his handful of years behind the mic for the RailRiders. “Kobe Bryant has died in a helicopter crash,” the text said, followed by a link to the story. “What?? Is this real?”

I don’t know if I’ve totally come to grips with the fact that it is, almost 24 hours after the helicopter he and eight others were flying in crashed into the hills just outside of Los Angeles. I don’t know if I ever will, or if I want to, and trust me, I’m not even a guy who had the Kobe Bryant posters or sneakers or even rooted for him throughout a basketball career in Los Angeles that put him firmly — and conservatively — among the top 20 players who ever dribbled a ball.

We see too much tragedy in life, of course. Maybe my earliest memory is of tragedy: I was 3. I walked out of my bedroom one night. My grandfather was babysitting my younger brother and me — my sister was born two nights earlier, and my parents must’ve been at the hospital — and he was just hanging up the phone with my aunt, who I could tell was upset. “She’s really sad,” my grandfather said, “because John Lennon was killed.” I remember feeling confused, because I don’t know if I knew what killed meant, never mind who John Lennon was.

I remember feeling profoundly afraid when, as a third grader simply excited to be taking a break from memorizing the multiplication tables for an hour, my classmates and I watched the Challenger explode. I remember feeling unabashed anger in 1995, watching coverage of the Murrow federal building bombing in Oklahoma City. I felt, more than anything else, frustration on Sept. 11, 2001, when I watched the World Trade Center fall, thinking this wasn’t going away, that pain from Oklahoma City was back, that we’d be leaving what I considered, naively, a mostly great world and entering an unknown one.

Sunday, for the first time after one of these tragic happenings, I felt sadness. Just…sadness.

“Why are you still watching the news, dad? Why is everyone still talking about Kobe Bryant?” my 7-year-old son said late yesterday afternoon.

And man, is that a long story.

Was he “one of us?”

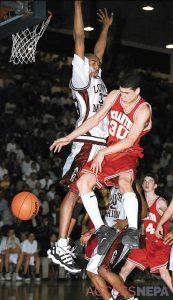

Kobe Bryant starred in a second-round PIAA playoff game against Scranton High School on March 13, 1996. “Obviously, that is the greatest high school team and the greatest high school player I’ve ever seen,” then-Scranton High head coach Jack Lyons, a Scranton-area basketball legend, said that night. (Times-Tribune file photo)

For those of us who came of age in the 1990s, Kobe Bryant will always mark our times. He was just a little more than a year younger than me, and he was easily the best basketball player in Pennsylvania when I was a high school student. I remember in 1996, Kobe’s Lower Merion juggernaut played Scranton High School in a second-round game in the PIAA playoffs. A friend called me the night before and said, “Hey, want to go watch Kobe run Scranton out of the gym tomorrow night? I’ll drive.” It was my 19th birthday, or I’d have gone. Kobe was an icon in Pennsylvania before he ever got drafted, and there probably haven’t been two high school players I’d have paid to see play before or since. (My esteemed colleague Marty Myers covered that game and wrote a really terrific story remembering it.)

I’ve seen a few friends on Facebook post that Bryant’s death hit them hard, because “he was one of us.” I kind of disagree. He was so unlike us. He was completely different. That’s what made him alluring back then. Mere weeks after that game against Scranton (he scored something like 25 points and called it a below-average performance, and for him, it probably was), he entered the NBA Draft, which is something high school players didn’t do with any kind of regularity back then. I actually watched the Draft that year, hoping my New Jersey Nets didn’t take him — I got my wish: they took Kerry Kittles. — because I just couldn’t picture a high school guard, as good as this one happened to be, going to the NBA and competing with those athletes as barely an 18-year-old, making an immediate impact in a league where Michael Jordan was still averaging 30, and Scottie Pippen and Charles Barkley and Clyde Drexler and Karl Malone and Hakeem Olajuwon and Patrick Ewing were larger-than-life, dominant figures.

Kobe wasn’t like us. He was the best of us. He did things on a basketball court that were better than I could do washing cars at the rental car company I worked at in the summers. He was a better basketball player than you are an accountant, or your buddy is a lab tech, or I am a sports writer. Greatness, when we recognize it, is something we root unabashedly for or, sometimes, hard against. But we gravitate toward it. We can’t look away from it. We try to understand it, to quantify it statistically and qualify it historically and apply it realistically, but we can’t. We don’t have the frame of reference. We’re mortals. Kobe was immortal.

Here’s what I couldn’t tell my son, because it’s too much to understand and, selfishly, too painful to say. It wasn’t just Kobe on that helicopter. It was his 13-year-old daughter Gianna, who was going to change the world. It was John Altobelli, the legendary junior college baseball coach in California who managed the former RailRiders outfielder Aaron Judge in the Cape Cod League (and Judge always spoke well of him), and his wife and daughter. This is a loss of young life, of talented life, of meaningful life that is so deep and steep and severe…

…It’s just hard to grasp it. How do you explain that to a kid?

Kobe Bryant was admired in his younger years because he wasn’t like us, but he should have been admired for many, many more years, because he became like us. He became a doting father. He wanted what was best for his children. He spoke of them glowingly and often; he shared stories of Gianna’s development on the basketball court more than he did his own successes in recent years. His daughters amazed him in ways he never amazed himself, and he could do some amazing things. He learned about himself what those of us who grew up in his time learned about ourselves, that we could love like we never knew we could, that what mattered in the past goes away when we stare into the eyes of our children, and all that matters is what we can do for them, what we can be for them.

How do you explain to a child who thinks you’re Superman that we’re affixed to our televisions on a Sunday afternoon because none of us are Superman? That life is a great adventure all too often punctuated by cruel reality? That there are things you just can’t understand and won’t ever understand and, maybe, aren’t supposed to understand?

How do you reconcile the idea that, in sports, you learn to be resilient and that you see so many examples of that resilience — that Magic Johnson got a death sentence in 1991 and is still impacting, that Kirk Gibson came to the plate on one leg in 1988 and hit a home run, that Tiger tore his ACL and won the US Open in ’08, that Jack Youngblood played in Super Bowl XIV with a broken leg, that Michael Jordan scored 38 in the playoffs with the flu — but a perfectly healthy Kobe leaves home to take his little girl to her basketball game and never got to the gym?

How do you explain that’s part of life?

Saying goodbye

I realize this is a Penn State football blog, and that this has nothing to do with Penn State football. But, it also has everything to do with football and baseball and soccer and tennis and hockey, because so many of today’s young stars idolized Kobe, respected his mentality and tried to incorporate that into their games, no matter their sport.

But we were lucky. We saw Kobe as a kid, watched him grow into a man, watched him dominate a league, watched him make pretty big mistakes, watched him overcome those mistakes and grow, watched him hoist the NBA championship trophy four times, watched him become his generation’s Jordan, watched him get old, watched him fade, watched him leave, watched him score 60 on the way out the door, shooting 50 times in his final game, trying to give us one more winter night on the hardwoods, striving to empty his own tank.

We saw the Kobe we were going to get. What we lost Sunday was what Kobe was going to give. We lost three young women who were part of his Mamba Sports Academy youth program. They were maybe among the most gifted players in their state, and perhaps the country. We lost the daughter of an NBA icon who had dreams of carrying on his legacy on the basketball court, of playing at UConn and in the WNBA. Gifted as she was, who knows what Gianna could have done for women’s basketball as she got older.

We can only guess.

But here’s what I do know: Kobe Bryant and the other parents on board died doing something they loved, spending time with their daughters, excited about a basketball game. Kobe died doing what a lot of people like you and me love doing. And we can relate to that. He’s just like us, in that regard.

“Why are you still watching the news, dad? Why is everyone still talking about Kobe Bryant?”

I did the best I could. I tried to explain it to him the way my grandfather explained John Lennon to me that night. “Because, he was great at what he did, and a lot of people really admired him for how he played basketball, and the person he was,” I told him.

I didn’t have the heart, maybe not even the words, to discuss what it means to be a father and to adequately explain the promise of youth and the fragility of life and the unfairness of fate, the cruelty of good lives taken at their apex, and others before they even got the chance to really start. We didn’t really lose a professional basketball player, because No. 8 and No. 24 will live forever in some form. We lost a good, loving father, and a few other good, loving parents, who had so much more to give, to teach, so much more of an example to provide. And we lost kids, which is where all our hopes live.

He’s only 7. He wouldn’t understand all that, and I should know.

I’m 42. And I can’t understand it, either.

Donnie Collins has been a member of The Times-Tribune sports staff for nearly 20 years and has been the Penn State football beat writer for Times-Shamrock Newspapers since 2004. The Penn State Football Blog covers Nittany Lions, Big Ten and big-time college football news from Beaver Stadium to the practice field, the bowl game to National Letter of Intent Signing Day. Contact: dcollins@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5368; @DonnieCollinsTT