BY WES CIPOLLA

GIRARDVILLE — In the 1930s, the folklorist George Korson was interviewing the inhabitants of Pennsylvania coal fields.

He asked an old miner’s widow if she remembered June 21, 1877.

“Indade I do, sir,” she said in an Irish brogue. “Will I ever forget it! A sad day it was in the hard coalfields, sir.”

What happened was burned into the community’s collective memory forever.

“When the hour of the hangings arrived for them poor Irish lads,” the miner’s widow remembered, “the world suddenly became dark and we had to burn our lamps. It’s Black Thursday it was, sir.”

On June 21, 1877, forever to be known as “The Day of the Rope,” six Irishmen were hanged at the Schuylkill County Jail in Pottsville, and four were hanged at the Carbon County Jail in Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe). Those 10 men were accused of being Molly Maguires, members of a secret society of Irish-American coal miners who believed violent rebellion was the only way to obtain justice from their cruel and greedy bosses.

John “Black Jack” Kehoe, who newspapers called “King of the Mollies,” was spared the Day of the Rope. But he was hanged for the 1862 murder of mine foreman Frank W. Langdon one week before Christmas 1878, leaving behind his wife, five daughters and his bar, the Hibernian House in Girardville.

Joe Wayne, Kehoe’s great-grandson and fourth-generation owner of the Hibernian House, recently discussed another “black day” in history: March 13, 2020. That day, he bought plenty of food and liquor to restock his bar in time for the annual Girardville St. Patrick’s Day Parade, of which Wayne is founder and chairman. The event draws thousands every year, and was attended by former President Bill Clinton in 2008. However, last year, all his preparation was for naught when COVID-19 forced the Hibernian House to close and the parade to be canceled.

“We were always taught that everyone had to entertain,” he said about growing up around the bar.

As a child, his weekends were filled with singing, music and jokes at the Hibernian House. Despite its Irish roots, all were welcome, and Wayne continues that welcoming tradition with the bands and crowds that choke the streets of Girardville for every St. Patrick’s Day parade.

“It’s so crowded in here every parade day that if you died then you couldn’t fall over,” Wayne said.

The bar has a collection of neon beer signs broken by lovers who pushed each other up against them.

JACQUELINE DORMER / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

A mural inside the stairwell of the Hibernian House in Girardville shows John “Black Jack” Kehoe, right, in a coal mine.

A Mollies theme

Even though the parade has been postponed again this year, shamrocks still adorn doors and windows throughout Girardville.

Behind the Hibernian House’s Killarney-green doors is a wood-paneled diamond in the rough. Wayne has the Irish gift of gab and a flair for mile-a-minute folk wisdom. He is prone to using his own colorful expressions (he calls using the Hibernian House’s bathroom “shedding a tear for the Queen.”) He tends bar just like his great-grandfather did, and stores his beer on the same 150-year-old wooden bar. Wayne says the exquisitely carved bar has been in the family “since Adam and Eve were runnin’ around.”

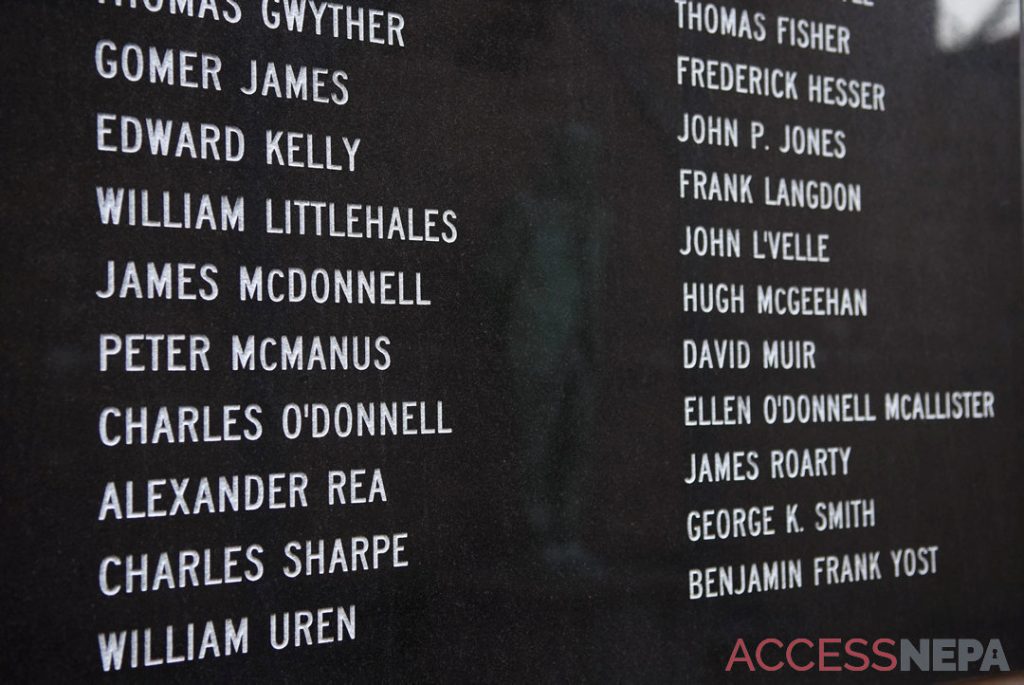

Above the bar are the names of the 20 men who were executed for crimes connected to the Molly Maguires.

“Let’s face it,” Wayne said. “Twenty men went to the gallows. Not one of them apprehended in the commission of a crime. Twenty men danced on the end of a rope.”

Wayne denies that there was a group calling themselves the Molly Maguires. He says its existence “was put on by the coal companies” to discredit the labor movement. “He wasn’t King of the Mollies no more than myself,” Wayne said.

The account found in most history books states the Molly Maguires were an offshoot of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, a longstanding Irish-American organization. Wayne is the president of AOH John Kehoe Division No. 1.

Although Wayne claims that “there was no such organization,” the Hibernian House honors the men who were called Molly Maguires. Portraits of Kehoe are flanked by the ornate candles used at his funeral Mass. What was once the door to his cell now leads to the women’s room. Portraits of Wayne’s ancestors, and the major players in the Molly Maguire drama, hang on the walls.

A large mural depicts the 20 hanged men standing at the bar with Wayne and his friends. There’s Gene Salay, of Doylestown, who was a prisoner of war in Korea (“they tortured him something fierce.”) There’s also Wayne’s lifelong friend, John M. Elliott, the attorney who helped clear Kehoe’s name by securing a posthumous pardon from Gov. Milton J. Shapp in 1979.

Wayne points out that his own likeness in the mural is thinner than he is, and missing his bald spot. That, he says, is what you pay painters for.

“There were a lot of discriminatory remarks being made about my great-grandfather,” Wayne said.

His uncle, Jack Kehoe’s grandson, was taunted for being “the grandson of a murderer.”

“That didn’t sit well with me, and that didn’t sit well with the family,” Wayne said.

Even when his mother was a little girl, she was tainted with the stigma of being descended from a Molly. The popular image of the Molly Maguires was one of violent outlaws – there were wild rumors of them throwing people on hot stoves, and cutting off the ears of those who crossed them. People joked that the survivors of the Molly Maguires looked like bighorn sheep, because they had to use ear trumpets to hear out of their surviving ears.

Starting when he was in college, Wayne researched his great-grandfather, but as he tried to clear his family name, some of his relatives said, “Let sleeping dogs lie.”

“Don’t stir up the stuff,” he remembered them saying. “I wasn’t the most popular guy in the family because of it. But I was gonna see it through.”

After years of lobbying, Shapp pardoned Kehoe 101 years after he was hanged. The framed pardon hangs in the Hibernian House.

“I was elated,” Wayne said. “I had an open house here and it lasted for three days. We had every TV station in the area. We had one heck of a party here.”

JACQUELINE DORMER / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

The Molly Maguire Historical Park off of West Centre Street in Mahanoy City photographed Tuesday, October 10, 2017. The monument is by sculptor Zenos Frudakis. Above the names read this: “From 1862 until 1879, The anthracite mining districts in Eastern Pennsylvania experienced a wave of violence attributed to the conflict between the Molly Maguires, the coal mine owners, the Catholic church, the Pinkerton Agency, the courty system and the residents of the region over that perio, scores of men and women lost their lives in the midst of that conflict. Some of the victims met their fate from the bullet of a gun, while others at the end of a rope. Many of those victims are named here:

First Irish here ‘weren’t saints’

John Kehoe was born in 1837 in County Wicklow, Ireland. He was among the thousands of Irish who fled the potato famine for America, and found work in the coal towns of Schuylkill County. He tried his hand as a miner, but found the most success when he opened the Hibernian House. The place became a popular hangout for Irish miners. These men who crossed the Atlantic brought with them a spirit of resistance against discrimination. In the 1840s, Irish peasants rose up in the face of economic hardship and mistreatment from the English elite. They would sometimes dress in women’s clothing, imitating a woman named Molly Maguire who may or may not have existed. The followers of this “Mistress Molly Maguire” delivered a form of vigilante violence that they called “midnight legislation,” targeting local authorities and rent collectors.

“When the Irish first came here,” Wayne said, “they weren’t saints.”

When these sons and daughters of Molly Maguire came to the coal region, the widows of mining accidents became the new Mistress Mollies. People like Kehoe wanted to fight for them. In time, Irish immigrants had built a Democratic political machine in Schuylkill County.

“Contrary to the papers that made them sound like ignorant Irish and so forth,” Wayne said, “they were school directors, they were tax collectors, they served on councils. They were very active in the community.”

At the heart of it was Kehoe. An educated man, he explained to the miners how they were being exploited. In those days, Schuylkill County was a Wild West of dangerous mines, unscrupulous owners and discontented workers. It was the kind of place where revolution was bound to break out sooner or later, it just needed a spark. That spark was the Civil War, which the Irish Democrats saw as “a rich man’s war, but a poor man’s fight.”

In June 1862, Frank Langdon, a mine foreman accused of ripping off miners when it came time to pay them, gave a speech in preparation for the Fourth of July. Kehoe was in the audience that day, and allegedly stepped on the American flag, spit on it and said, “I’ll do worse than that before this night’s over.” Shortly after Langdon finished his speech, an angry mob beat him to death. Witnesses claimed to have heard Kehoe say, “You son of a bitch, I’ll kill you!” Kehoe was hanged on this evidence.

Every ethnic group had its own interpretation of what happened, shared in each of their saloons.

Meanwhile, miners were becoming angrier about their poor wages and even poorer working conditions. They wanted to band together and fight for their rights — and the Ancient Order of Hibernians was the way to do it.