So many movies on this list got there because I take sports far too seriously. The Mighty Ducks was a fine movie when I first saw it as a 15-year-old in 1992, and it got two installments on this list after years of hanging around locker rooms and talking to managers and coaches and players and understanding how success happens; You can’t be a bad, do-nothing coach who gets great results. Field of Dreams is on it because in sports, the small details filmmakers ignored actually do matter, and that feeling developed over time too. The Natural is on it, because I’ve learned in my career to root for good people, not necessarily for great accomplishments.

So many movies on this list got there because I take sports far too seriously. The Mighty Ducks was a fine movie when I first saw it as a 15-year-old in 1992, and it got two installments on this list after years of hanging around locker rooms and talking to managers and coaches and players and understanding how success happens; You can’t be a bad, do-nothing coach who gets great results. Field of Dreams is on it because in sports, the small details filmmakers ignored actually do matter, and that feeling developed over time too. The Natural is on it, because I’ve learned in my career to root for good people, not necessarily for great accomplishments.

I was a junior in high school when Rudy hit theaters. A senior in my English class said it was the feel-good movie of the year. I couldn’t wait to see it. I was, after all, as big a Notre Dame fan as you’d find at my high school. And I’m sure many people reading this are going to think that’s a lie. It’s absolutely, 100 percent — I swear, on the soul of George Gipp — the truth.

If I have a pet peeve that has developed during my career working as a sports writer for The Times-Tribune, it’s this: Some of you just kind of assume I grew up enthralled with Penn State football, because I cover it for a living now. I don’t blame anyone for thinking that, honestly. I went to Penn State, after all. Had a great time there. Met many of my best friends there. But I assure you, if I wrote about something that happened on the football field at Penn State before the fall of 1995, chances are I had to research it. But man, I could tell you everything about Tim Brown and Ricky Watters and Mike Stonebreaker and Chris Zordich. Whenever someone asks who the best college quarterback ever was, I make an impassioned plea for Tony Rice running the option. Ask me today who my favorite college player ever is, and it’s still the Raghib Ismail. Growing up in Avoca, a largely Irish-American town in the 1980s, The Rocket made Notre Dame feel like the home team. In my hometown, it was.

I was the only Notre Dame fan in my family, really. Thrilled as I was after the national championship in the 1989 Fiesta Bowl, I knew everyone around me was rooting for Major Harris and West Virginia to pull the upset. I died a little when Craig Fayak’s field goal soared through the uprights in 1990 to give Penn State a season-ending win over my No. 1, unbeaten Irish, but that may have been the most satisfied I’ve ever seen my Dad, who is not a sports fan by an means, at the result of a sporting event. The Irish’s lost to Boston College on a last-second, 41-yard field goal might be the hardest one I ever suffered as a fan to that point.

For a time, I’d record Notre Dame games on my VHS in Happy Valley, to watch them after my friends and I got back from Beaver Stadium on Saturday afternoons. To this day, I still have great respect for Notre Dame’s program and hold the utmost reverence for the university. If any of my sons come to me someday and show me an acceptance letter from Notre Dame, it will bring tears of joy.

But the foundation of my die-hard fandom began to crack the day I saw Rudy.

I think we all know the story of the film, so there’s no reason to go into great detail rehashing it. Basically, Daniel Ruettiger grows up a couple of hours outside of South Bend in Joliet, Ind., dreaming of playing football for the Fighting Irish. He’s a hard-nosed player, a kid who never gives up — all of that is established early — but he’s a defensive and who is really, really small. Like, 5-foot-6. And his academic work is barely at a community college level.

With no shot to get into Notre Dame, he takes a few years off. In real life, he joined the Navy and worked at an electrical plant. In the film, while working at the plant, he watches his close friend — the only one who really believes in him — die in a fiery workplace accident. That steels Rudy’s resolve to live his dream; to get into Notre Dame and play football for coach Ara Parseghian (played wonderfully in the film by Scranton legend Jason Miller).

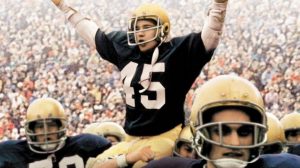

Rudy Ruettiger was the first player in Notre Dame history — and the only one until the mid-90s — who was carried off the field by teammates.

There’s still an issue: Rudy can’t get into Notre Dame as a student. He’s not even close. A priest sees his passion and helps him enroll at nearby Holy Cross College, insisting that if his grades are good enough, he can perhaps transfer in. Rudy, in the meantime, is homeless and struggling and gets a job working on the grounds crew at Notre Dame Stadium. He gets a tutor who helps him learn that he has dyslexia, and once he realizes his learning disability and can deal with it, Rudy’s grades improve.

Still, his parents and family members don’t just doubt his ability to accomplish his dream, they outright mock his pursuit. His brother has stolen his ex-fiancee, but the joke is on him. On his fourth attempt to get into Notre Dame, Rudy is accepted.

He attends walk-on tryouts, and he is told what all who go to walk-on tryouts are told: Essentially, they’re tackling dummies. Nobody is guaranteed anything as far as making the team or even suiting up, never mind playing time. That’s what the scholarship players are for, and the scout team guys are there to get the scholarship kids ready, and that’s that. But Rudy’s determination shines through, and he indeed makes the scout team, where he impresses the staff with his can-do attitude, if nothing else. Whether it be because he had absolutely nothing to lose or simply through unmitigated gall, Rudy marches into Parseghian’s office and asks Ara if he will suit him up for one game as a senior. Ara readily agrees.

Dan Devine, who did as much as anybody in real life to get Rudy on the field, was his biggest detractor in the film.

Ara then retires. In comes Dan Devine, who treats Rudy more as a mascot than a serious competitor for playing time. The weeks pass, and Rudy’s name is not on the dress list. Clearly, Ara Parseghian didn’t call Dan Devine on his way out the door and relay the promise he made to that 27-year-old walk-on kid from Joliet. Dress list for the final game of the season comes out and, of course, no Rudy.

So, Rudy — who built his reputation on never quitting — quits.

You then get the two really famous scenes in the movie. In the first, Fortune, the head groundskeeper who took Rudy under his wing, encounters Rudy brooding in the tunnel and drops truth bombs about what’s really important. It’s easily my favorite scene in the movie.

Then, we move to Devine’s office, where Notre Dame players are staging a quiet revolt. They’ve come to respect Rudy over the years, and they think he deserves to dress for a game. So, they all hand their jerseys in to Devine, symbolically forfeiting their chances to dress so Rudy can have his.

Devine reluctantly lets Rudy dress for the finale against Georgia Tech, and he even more reluctantly lets him play once the game is decided because fans and players are chanting his name. On the final play of the game, Rudy sacks the quarterback and is carried off the field in triumph.

Great story. And some of it is actually true. Rudy Ruettiger did live his dream of playing at Notre Dame. He did graduate from Notre Dame. He did get carried off the field. He did work his backside off to accomplish all of that. And even before the movie, most Notre Dame fans knew that story.

This movie made that story more widely known, but the ultimately truth was largely clouded by an attempt to dramatize an already dramatic story.

The jersey scene was clearly fictional, and anyone who knew the Rudy story would know that, because anyone who knew the story would realize there’d be no reason for it to ever happen. Suiting Rudy up for the last game, after all, was totally Dan Devine’s idea.

So, in the movie, the villain who didn’t understand the value of hard work and dedication and dreams was actually, in real life, the guy who understood all of it so much, he made Rudy’s dream come true. Ruettiger himself said the movie was about 90 percent true, and I’m sure that’s right. He also has said in several interviews, including this one with USA Today, that the message is more important than the facts.

But you can get the message through without bastardizing the facts. I had the pleasure once of interviewing Bill Yoast, the legendary Virginia high school coach who was Herman Boone’s assistant on the 1971 T.C. Williams High School team immortalized in Remember The Titans. He had some fun talking about how different the movie was than the real life experience. For instance, the dramatic finish of the movie’s state championship game — Rev’s Fake 23 Blast with a Backside George Reverse “like your life depended on it” — actually happened. It just happened in the fourth or fifth game of the regular season; there was little actual drama on the field that season, because that defense only allowed points in a handful of games. But, “You know Disney,” as Yoast told me that day. Remember The Titans dramatized some stories, but to certain degrees, those stories actually happened.

In other words, I’m OK with a little bending of the truth. I’m not OK with rewriting history. What if someone wrote a movie about Derek Jeter’s rookie season and included several scenes about how his manager, Joe Torre, never believed in him. What if Torre pouted when Tony Fernandez got hurt heading into ’96? What if Torre, in the film, pitched to have him traded to Seattle for Felix Fermin? Would have made the story more dramatic, for sure, right? It also would have been absolutely ridiculous.

Always wondered whether Notre Dame’s reverence for Ara Parseghian (played here by Scranton’s Jason Miller), who guaranteed Rudy a chance to play before retiring, contributed to movie’s depiction of his successor, Devine.

The Rudy story is great. At its core, it’s what college athletics are all about. But I’ve seen Rudy try to defend the treatment of Devine in the film over the years as necessary to taking the spirit of his own story mainstream, and frankly it’s nauseating. Devine won a national championship with the Irish in 1977, coached Joe Montana in the chicken soup game against Houston in the ’79 Cotton Bowl, and won 76 percent of his games overall as Notre Dame’s coach. But he was never embraced as much as he should have been — Notre Dame fans were constantly looking to run him out of town, almost from the start; the price of following a legend — and I do wonder if that fact kind of made him an easy fall guy to make the Rudy story an even bigger legend for Notre Dame.

Regardless, this wasn’t the feel-good sports movie of that year, as my old classmate said. It was a movie that took such liberties with the truth that it spoiled the real story on me. It was a wonderful story that didn’t have to sully a reputation to be wonderful. But, it did anyway.

Donnie Collins has been a member of The Times-Tribune sports staff for nearly 20 years and has been the Penn State football beat writer for Times-Shamrock Newspapers since 2004. The Penn State Football Blog covers Nittany Lions, Big Ten and big-time college football news from Beaver Stadium to the practice field, the bowl game to National Letter of Intent Signing Day. Contact: dcollins@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5368; @DonnieCollinsTT