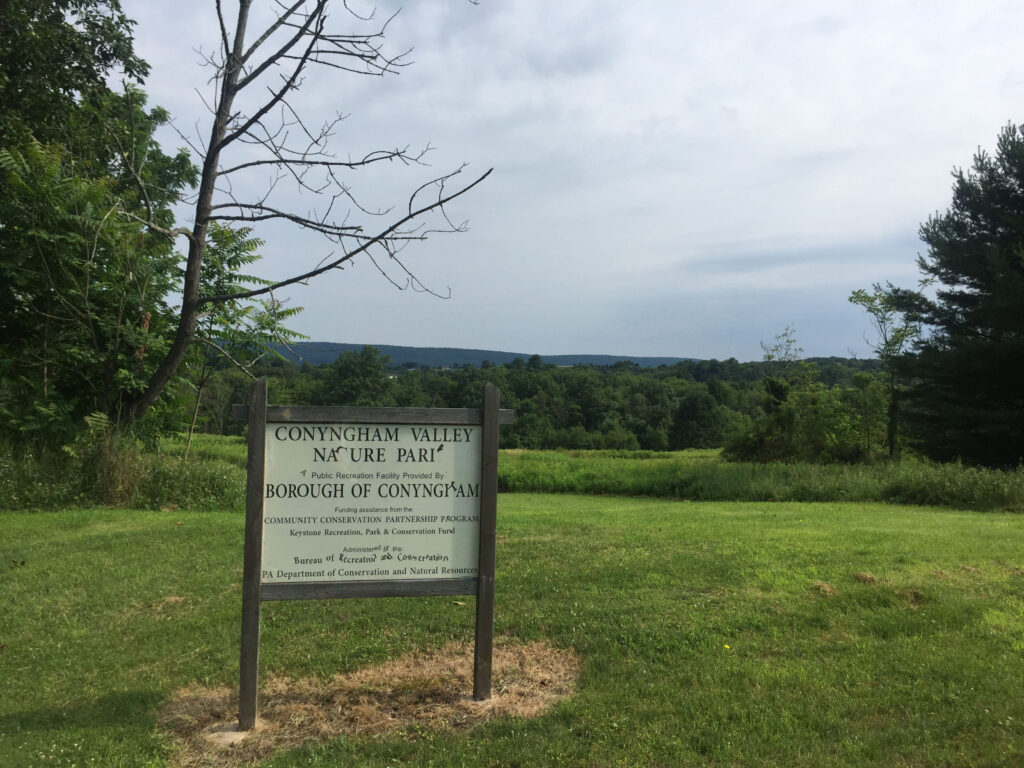

Conyngham Nature Park is one-quarter mile from Main Street, but when I’m on the bottom of the trail looking up the tree-covered hillside toward Conyngham Mountain I can trick myself into thinking it’s still wilderness.

At least until a tractor-trailer, toy-sized in the long-distance perspective, inches up Route 93 too far away to hear.

Smart planning eight years years ago kept much of the land intact.

Elsewhere nearby, walkers take to trails at Freedom and Butler Twp. Community parks and Hazle Twp. Community Park and the region’s network of rail trails. Hazleton Mayor Jeff Cusat is interested in repairing trails around the city’s Sky View Park, and trails are in the design stage at storm water parks that the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority envisions.

Parks don’t always need swings, ballfields or pavilions.

Sometimes, a place to walk and something to see will suffice.

Krista Schneider, a landscape architect who worked on the Conyngham Nature Park, said views haven’t changed a lot since before settlers arrived more than two centuries ago. In addition to looking up toward Conyngham Mountain, walkers can peer downhill from the main trail past a stream, a pond that is silting into a marsh and see farmlands.

Plans call for adding rights-of-way so walkers can travel downstream to Conyngham’s other park, Whispering Willows.

When Schneider explored the nature park’s land, she noticed a foundation of a barn built in the 1840s when a family named Bishop farmed there. Their farmhouse along School Lane dates to then, although it was damaged by fire in 1987 and remodeled.

Schneider thought Conyngham might someday add signs marking the barn site and explaining more about the land.

“I was interested from a kind of historical perspective, just using it as a way of interpreting the Conyngham Valley from an agricultural perspective,” she said.

Before farmers arrived in Conyngham Valley, a Revolutionary War episode put the area on the map. On Sept. 11, 1780, Native Americans and their Tory allies decimated a detachment of colonial militia in what is now called the Sugarloaf Massacre.

A historical marker for the massacre stands along Walnut Avenue south of and parallel to the nature park.

In the park, landscapers mow a wide border on either side of the walking trails.

Otherwise, the land is meadow — waist-high grassland and young forest — something that land stewards seek to create more of at Nescopeck State Park and other natural areas.

“There’s just a lot of diversity in that little area,” Schneider said. “The stream, flood plain, the grass, the viewshed is pretty well preserved.”

In the past few weeks while walking dogs, I’ve seen robins, sparrows, crows, but also flashes of color. Bright yellow goldfinch and a blur of blue:

In the past few weeks while walking dogs, I’ve seen robins, sparrows, crows, but also flashes of color. Bright yellow goldfinch and a blur of blue:

Jay?

Bluebird?

No, the deep hue of an indigo bunting.

Dragonflies and beetles emerge from the meadow.

I saw a brown butterfly with an orange eyespot on its wings that I didn’t recognize.

Checking the “Family Butterfly Book” by Hazleton’s Rick Mikula, I found out it is a buckeye, the only butterfly on the continent with such a bold eye.

There also are rabbits, woodchucks and squirrels.

Often I see deer, either in the park or yards nearby.

The other day, a deer reached its head above the meadow. A triangle of ears and nose was all I saw.

The dogs, nosing the ground, didn’t notice was we rounded a turn and climbed.

I paused and looked down.

The deer, bent to graze again, nearly vanished into the thicket.

Even after three decades as a reporter at the Standard-Speaker, Kent Jackson still enjoys meeting people, learning more about the community and sharing stories with readers. He currently covers schools but has reported on local government, health, police and the environment. Regularly, he writes about outdoor sports, wildlife and conservation for the Wildlife page on Sundays. Contact: 570-455-3636; kjackson@standardspeaker.com