BY LEAH ZERBE

When you check the map, Schuylkill County is as red as it gets.

But this isn’t a political map or even a coronavirus map we’re talking about.

It’s a radon map.

Schuylkill County is part of the “radon belt,” locations that run a high risk of harboring dangerous levels of the radioactive gas. It quietly seeps from the ground and builds up in homes, schools and businesses.

Radon starts out as uranium, something that naturally occurs in soil and rocks. But as it breaks down, it becomes highly mobile and weasels its way into all types of structures, old and new, and even those without basements.

No matter where you live, the only way to know if radon poses a threat is to test on a regular basis, since radon is tasteless, invisible and odorless.

And for my family, it’s personal. In 2015, I lost my father, who never smoked, to lung cancer. He was only 61. My grandfather, who lived in the same home, also died in his early 60s. It’s quite possible radon played a role in both of their deaths.

Radon causes an estimated 21,000 lung cancer deaths in America annually. Behind smoking, it’s the most common cause of lung cancer and kills more people than other household threats like falls, fires and drownings. Researchers are even investigating a link between radon exposure and COPD.

When the hospice nurse asked if my father smoked, I said no … never. She nodded her head in disappointment and said, “Yeah, we see a lot of this in the area.”

Radon gas is especially common in Pennsylvania; an estimated 40% of homes contain radon levels above the Environmental Protection Agency’s action guideline of four picocuries per liter.

But here’s the thing: I vividly recall my father performing a radon test when I was little.

“Keep the windows closed. Don’t leave the door hanging open,” he instructed. When the results came back, they were just below the EPA’s action level.

The need to retest

After my father’s death — more than 20 years after that original test — we performed another radon test. Levels were six times higher than the EPA’s action level. Shifting foundations, household projects and even water can create new avenues for the gas to enter a home. Because of that, the National Health Advisory on Radon suggests radon testing every two years, with a retest if you make structural changes to your home or if you occupy a previously unused level of your house.

New threat: “Fracked” natural gas

A 2019 study found living near natural gas wells using hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” to extract the gas increases a household’s exposure to radon. Other research suggests you could get small exposures in the home from cooking with natural gas. (So be sure to use ventilation if you cook with natural gas.)

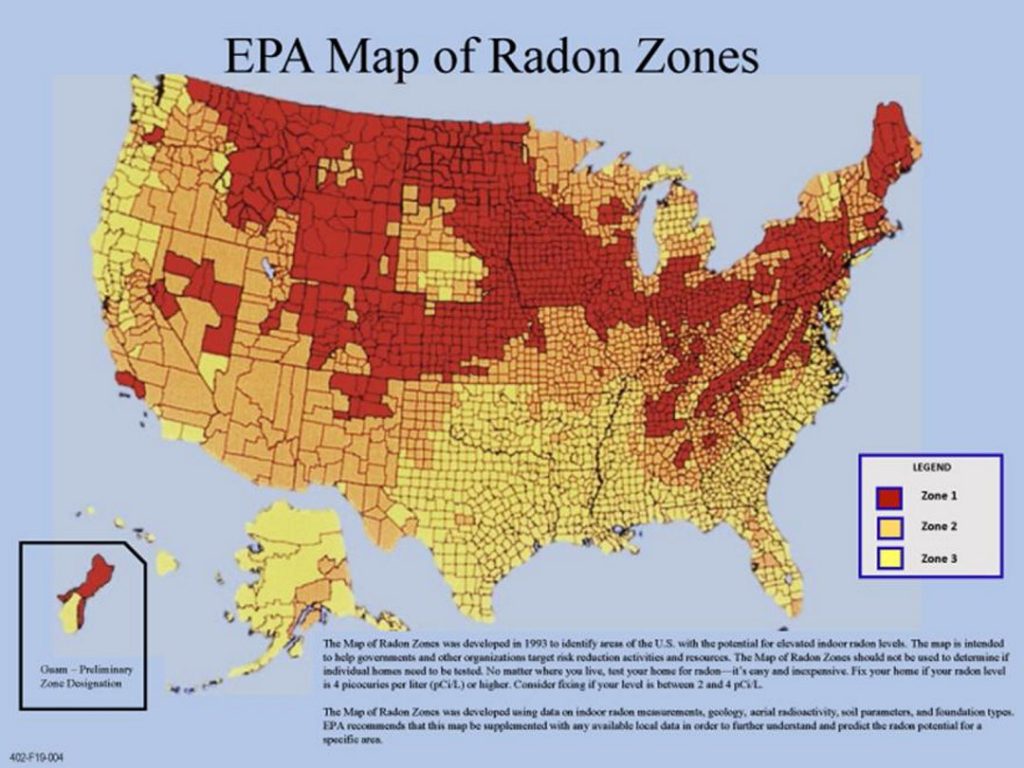

SUBMITTED PHOTO

EPA map of radon zones

We need the medical field to step up

Visiting the doctor’s office, we typically answer a number of standard questions.

“Do you smoke? If yes, how many cigarettes (or packs) a day?”

“Do you drink? If yes, how many drinks per week?”

“Any recreational drug use?”

And even, “How have you recently traveled outside of the United States?”

But there’s one crucial question doctors and nurses generally aren’t asking, and it’s crucial to this area: “When was the last time you tested your home for radon?”

This needs to become a standard part of every visit if we want to truly save lives.

A pretty easy fix

If your levels are high, don’t panic. Most radon systems run about $1,200 and can be installed in a day by a certified radon mitigation contractor. Just note: many new homes are equipped with radon piping but aren’t complete until a certified radon fan is installed properly to suck the gas out.

For more information, and to see if you qualify for a free or inexpensive test kit, call PA Department of Environmental Protection’s radon hotline at 800-237-2366. You can also call 717-783-3594 for help, or email ra-epbrpenvprt@pa.gov.

The EPA’s Consumer’s Guide to Radon Reduction: How to Fix Your Home is another robust resource for more information.

Zerbe can be reached at leah.zerbe@gmail.com.