Ron Rumford has a shuttered school and a forward-thinking teacher to thank for changing the direction of his life.

The Carbondale native and art gallery director had planned to move to Pittsburgh after graduating from high school in 1980, but in late May, he learned the small commercial art school he was to attend was folding. The school told its students they’d attend classes at a similar school in Pittsburgh instead, but Rumford decided to give his plans another look.

Some teachers recommended other art schools, and a music teacher at Carbondale Area offered to take him along on a trip to Philadelphia. She pointed out that the Philadelphia College of Art would be near where she was stopping, and she suggested that Rumford try to get an interview there.

“In retrospect, I realize she got me she understood me probably more than I understood myself,” Rumford recalled.

He quickly put his portfolio together, met with school officials and was offered a place in the incoming class on the spot.

“It was that serendipitous,” said Rumford, who earned a bachelor’s degree in painting and drawing there.

“I came here to go to college and then forget to ever leave,” he joked. “And it’s been a very good thing for me, a good setup.”

Rumford, 58, was born in Fort Meade, Maryland, while his dad was serving in the Army. The family later moved back to Carbondale, where his parents, Robert and the late Shirley, had grown up. He knew from around sixth grade that he wanted to pursue a career in the arts.

For Rumford, the second of six children, he saw art as a chance to make “something that was kind of completely my own.” He loved doing school art projects, and as he grew older, he found other opportunities to develop his skills, including evening classes and private lessons.

In college, Rumford took what he described as a rigorous course of painting and drawing along with art history and more. Studying with “really remarkable artists” made for a fantastic experience, he said.

“To meet someone that was that kind of mentor and role model — it was sort of a golden moment at the college where all the professors were really interesting artists,” Rumford said.

After graduating, Rumford took a job cooking in a Philadelphia restaurant but also kept his eyes on the art world.

“I enjoyed learning about food, which I did, and I worked in a very nice restaurant, but it was not a very satisfying or sustaining experience,” he said. “And so I used to visit this gallery, Dolan/Maxwell.”

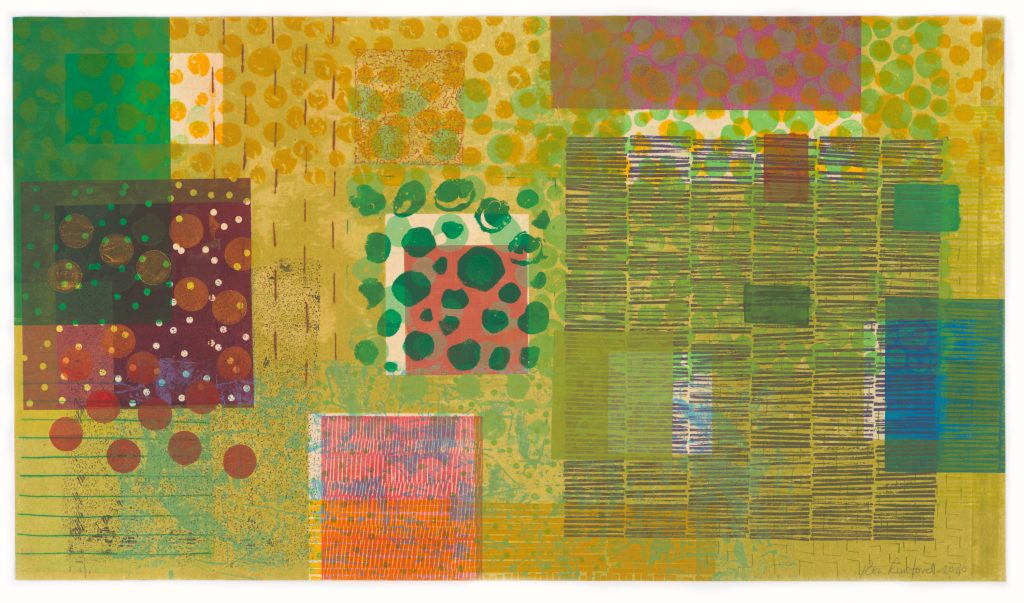

SUBMITTED PHOTO

Ron Rumford’s piece, “Confusion of Pleasure.”

A college acquaintance was working at the gallery at the time, and told Rumford they needed some part-time help. He started there in 1985 and worked his way up to director, a position he’s held since 1991.

Rumford had entered the art scene during a period of boom. Dolan/Maxwell had a large gallery on Philadelphia’s Walnut Street, where they’d host exhibits every few weeks, and it later added a gallery in New York City.

But around 1990, Rumford said, the art market collapsed. The owners of Dolan/Maxwell closed their New York gallery and decided to take some time off, heading to Ireland to focus on a project there. They wanted to continue working with Rumford, though, and see their namesake gallery continue, so he took charge to make that happen in their absence.

“They went to Ireland, and I was here on my own,” he recalled. “We went from having a public gallery to being what is called a private dealer. So we still have a collection of art and we still work with artists and the estates of artists, but we don’t do shows. We don’t hang shows and have people who come in.”

Instead, the gallery works with private clients, such as art collectors and professionals in the field, by appointment. Based in a former carriage house near Rittenhouse Square, Dolan/Maxwell focuses on work from the 1930s to today, mostly prints and other works on paper but also paintings and sculptures that complement its other pieces.

When he took charge in the early ‘90s, Rumford had a shoestring budget to work with. He started doing art fairs and brought in new artists, and eventually, the market grew again, letting Rumford hire a bookkeeper and some temporary help.

Art fairs keep Rumford busy and takes him to spots such as Chicago, New York and Cleveland.

“The idea is that you create this sort of mini mall of art with the idea that (you bring) everything together in one place, and then you invite a big audience,” he said.

While a gallery show might only draw 50 to 100 people at its opening and then a few dozen more over the following month, art markets bring in thousands of people. It involves a lot of hard work and preparation to get pieces there safely and set it all up like a small gallery.

“You have to be on an ready to talk to people,” Rumford said. “But they’re lots of fun, and they’re a way to constantly meet new clients.”

No two days are alike in his job.

“The artists have kind of become friends; the clients become friends,” Rumford said. “The art changes. The market changes. I’m constantly learning new things.”

The nature of the art he works with — pieces by living artists but also older works — holds his interest, too.

“I always liked history, so that became something that I really, really enjoyed — that you could go back and find out about the artist and what he or she made in the ‘30s or ‘40s,” Rumford said. “So it’s kind of like a great big research project. … It’s never static.”

Throughout his gallery career, Rumford has continued to make his own works, the focus of which changed thanks to what he handled in his day job.

“The focus is art on paper, so a lot of limited-edition prints by artists, in some cases, of international renown. … I went through college, and I was ignorant, honestly,” he said. “I didn’t know what a fine art print was. So I didn’t study it, and then I ended up in this gallery and I was surrounded by it. So I was sort of converted by osmosis.”

Rumford had continued to paint, but working with oils proved problematic since they can take days to dry. He’d paint for a bit, get busy with life, then come back to his painting only to find he’d lost his connection to the piece. So he decided to take a printmaking class and found his niche, and over time he’s developed his own style of printmaking.

“What was interesting to me was that I could make the plate, and I could change the color, and I could wipe the ink or leave some on, and you could change it and layer it,” Rumford said.

He sees printmaking as a matrix, and once he sees that matrix, he said, “they’re kind of toys you can just play with.”

“I can take plate and ink (it) in a certain way and pair it on a piece of paper with plate. … So I have this sort of system or language of different matrices.”

Rumford, who keeps a studio at his home in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, never knows what a piece will end up as. He’ll come at it with a few ideas, and over the following months, the pieces evolves.

“I have an idea about what it’s going to do, but I don’t really know about how dense the ink is going to be. … It’s sort of ‘call and response,’ Rumford said. “I’m always trying to take it in a different direction. I’m trying to surprise myself.”

Several times, Rumford also has participated in the Ireland-based product the Dolan/Maxwell founders started all those years ago: a residency program in County Mayo. The Ballinglen Arts Foundation invited artists for fellowships and provides housing and studio space.

“I’ve been really really lucky. … It’s a place that people don’t know about, and it’s unspoiled. And there’s more sheep than people and cows, so it’s wonderfully remote.”

The village of just a few hundred people sits on Ireland’s west coast, where Rumford has watched the constantly changing Atlantic sky, with its “wonderful light and lots of rain.”

“I definitely feel like it kind of resets things when I’m there,” Rumford said. “And as life became more complicated with telephones and devices and email and these kind of hyper-connected lives that we lead right now, you kind of go there and you feel like you’re far, far away from it, and you’re back to being your own self.”

SUBMITTED PHOTO

Ron Rumford’s piece, “Excellent Spirits.”

Rumford recently showed some of his work in Ireland at the inaugural exhibition at the Ballinglen Museum of Art. He’s also exhibited in galleries in Philadelphia and New York City, and more than 50 collections around the world contain his work, including the Boston Public Library and the Cleveland Museum of Art. His work was included in Pennsylvania’s annual Art of the State exhibit in 2010, and he has served on the art advisory board of Penn State University’s Palmer Museum of Art since 2012, a group he has chaired since 2017.

He takes the occasional break from the studio but eventually he starts itching to get back to work.

“(Art is) still a place that I kind of need to go to,” Rumford said. “It’s still where I can be in my own headspace. So I need it.”

In August, Rumford gave a Zoom-based presentation for the Print Club of Cleveland, which had commissioned him to make a print. While he couldn’t attend in person because of the pandemic, it nevertheless made for a “prestigious honor” of which he’s proud.

And this fall, Rumford, who has a second home in rural Susquehanna County with his partner, Steven Ford, put his art before a local audience with an exhibit at Waverly Community House. He spent the summer preparing for ”Shelter in Place: New Works by Ron Rumford.” Rumford expected the Comm would have to cancel the show because of the coronavirus, but it went on, and Rumford said they had a great turnout.

“Lots of friends from high school were there, and people that I hadn’t seen in like 40 years turned up, so it was a really, really kind of wonderful homecoming celebration,” he said.

Rumford encourages aspiring artists to pursue their passion — and for their parents to support them. He recently met a set of parents who, despite their own creative career as architects, were worried about their son wanting to go to art school. One of Rumford’s own brothers studied cartography in college, and while he didn’t end up in that career, Rumford said, the studies fed his curiosity. And Rumford asks himself a similar question in creating his own art: does it nourish him?

“What’s important is, certainly, if you have a kid who has an idea about what they want, maybe they don’t become a successful artists, but they’ve chased their passions,” he said. “They’ve chased their love. And that’s going to tell them who they are, and that’s going to set their standard for hard work and excellence, so that’s going to serve them no matter what. That’s going to be OK.”

Caitlin Heaney West is the content editor for Access NEPA and oversees the Early Access blog in addition to working as a copy editor and staff writer for The Times-Tribune. An award-winning journalist, she is a summa cum laude graduate of Shippensburg University and also earned a master’s degree from Marywood University. Caitlin joined the Times-Shamrock family in 2009 and lives in Scranton. Contact: cwest@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5107; or @cheaneywest