Early last week, as is sometimes the case, as the day started, my iPhone had already received several text messages. One caught my attention.

“Dick Bagnall will be Man of the Year” — sent by Dream Game player/coach liaison Jerry Preschutti.

It brought a huge smile to my face.

Each summer the Scranton Lions Club remembers and honors people for their commitment to local high school football with this prestigious award at halftime of the annual summer all-star classic that will be played this season on July 17 at 7 p.m. at John Henzes/Veterans Memorial Stadium.

Today in The Times-Tribune, we have the obligatory recap of Bagnall’s Hall of Fame career.

PLEASE CLICK LINK TO READ:

HS FOOTBALL: Dick Bagnall to be honored as Man of the Year; Media Day is Monday

Honestly, though, this tells only a small part of the man, Dick Bagnall is and what he means to the Susquehanna Community, and to this sports writer.

In 1994, when getting a job in the industry was as difficult as scaling Mount Everest, I penned stories for a now defunct weekly all-sports newspaper. Bagnall had just guided his Sabers to their historic victory over Lakeland, a team I served as an assistant coach, in the District 2-12 Class 1A subregional playoffs, and followed that up with a wild win over Schuylkill Haven where Jake Reed ran for 334 yards and four touchdowns in the first round of the PIAA playoffs.

Before cell phones and text messages, landing an interview with the high-flying coach took some effort. My father, who was station commander for the Pennsylvania State Police barracks in Gibson, helped arrange a sit-down interview with coach Bagnall and Reed at Duchnik’s Gas Station off Interstate 81.

Coach Bagnall and Reed couldn’t have been more gracious. And while my writing chops were still very raw, I did a wonderful insight into their relationship and what their victories meant to the tiny community in Susquehanna County.

He never forgot.

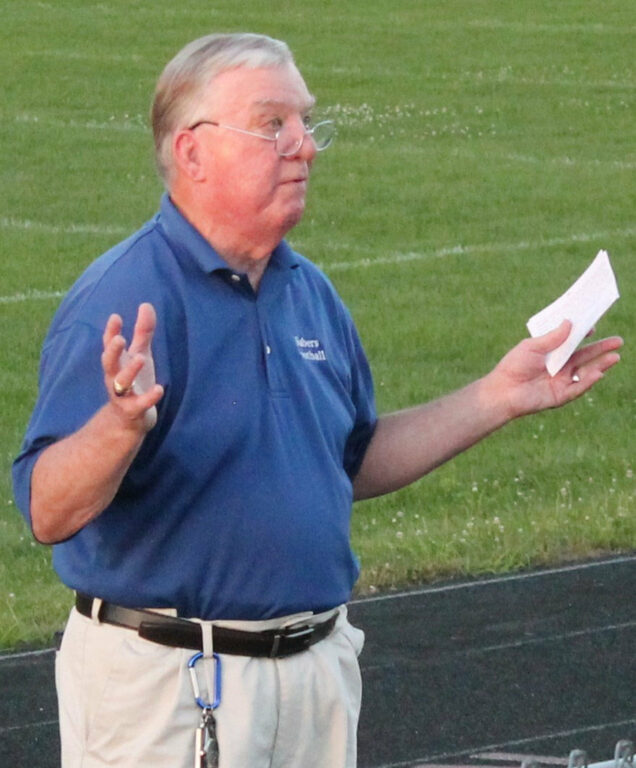

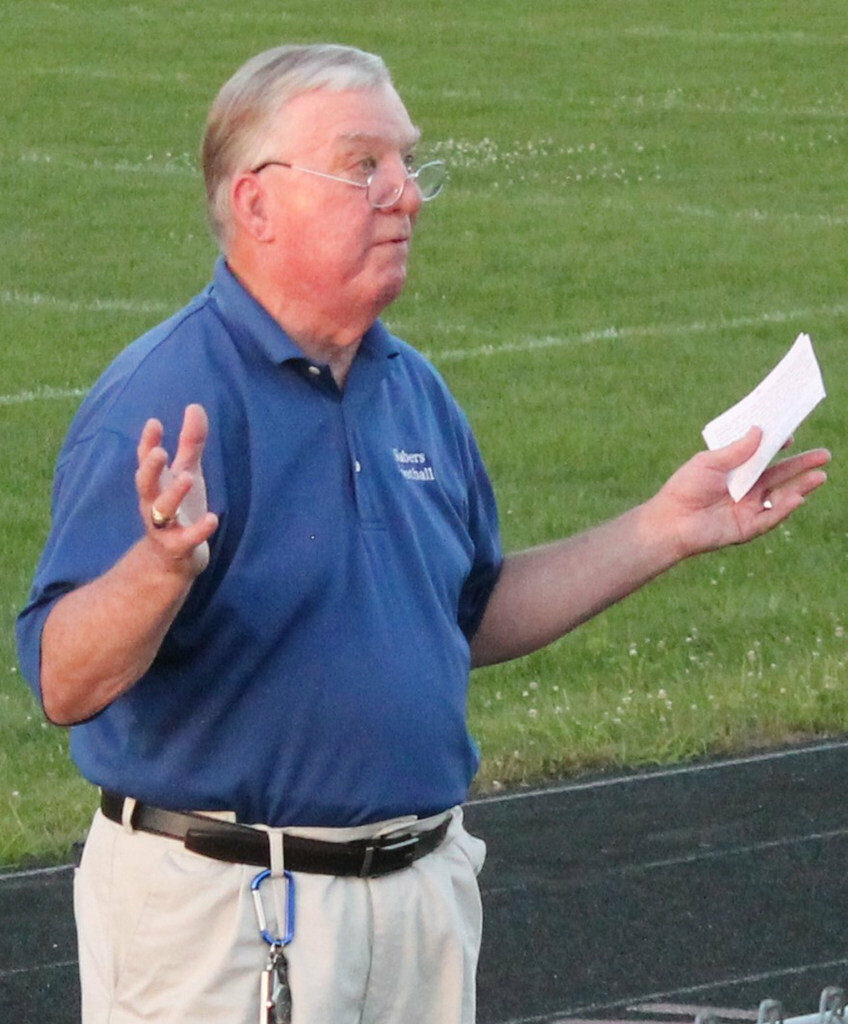

Dick Bagnall

Five years later, I started my career as the high school football writer at The Times-Tribune. I had very little experience in budgeting and the logistics of the position, and kind of got thrown into a boiling cauldron. On my first assignment covering the Sabers, Bagnall, who was no longer the coach but a dominating figure at games as athletic director, extended his arm, shook my hand, and said, “I’ll never forget that story you wrote about me and Reed.”

From that day forward, coach and I have had a really engaging relationship. I’d like to say that it’s exclusive, but when one of my best friends, Bob Goodrich, became a teacher and assistant coach at Susquehanna, it became abundantly clear Bagnall’s warm demeanor was genuine, and his personality overly endearing.

Without fail, after making the trip to Susquehanna to cover his team on a Saturday afternoon, Bagnall would seek me out, thank me for taking the time to cover the Sabers, then reminded me of my open invitation to the Moose Lodge. I never had the opportunity to sit side-by-side with him at the King’s palace (the job and all), but he would say each time, “I’m going to get you there someday.”

Susquehanna quarterback Anthony Dorunda, shown here against Scranton Prep, scored the game-winning touchdown in the Sabers’ 7-6 victory over rival Montrose in 2005.

HARD TIMES

Susquehanna, like many small rural schools, saw participation and interest start to wane in the late 1990s. Excitement about playing for the Sabers, which had once been a rite of passage at the school because of the tradition Bagnall built, became tempered.

When the Big 11 and Suburban Conferences merged, a move fueled heavily by Susquehanna’s win over then Big 11 power Lakeland in 1994, the tiny outlying programs found out just how daunting a task it would be to field a competitive team on a consistent basis while playing a more physically demanding schedule.

The Sabers went into a tailspin and dark days were ahead.

Beginning late in 2001 and running through 2004, Susquehanna played and lost 26 straight times. A coaching change came in Week 4 of the 2004 season. Bagnall came out of retirement to save what he built. He brought with him his veer-option offense, a scheme he became famous for implementing that kept defenses off balance and gave his sometimes overmatched players a chance.

His first game back, interestingly, came against Lakeland, which was in the middle of steamrolling teams locally, and did so in a 54-13 win.

An eternal optimist, Bagnall, who knew that when it worked and was executed properly, his multi-option veer attack would eventually give teams migraines, and he looked into the future:

“This was a learning experience. (Anthony) Dorunda started to learn how to run the offense. It’s the first game against a very, very good football team. We put the ball on the ground, yes, but I look at the positives. “We did some good things. We are young.”

Susquehanna’s losing streak reached 34 games before Bagnall turned things around. The Sabers ended the drought with an emotional win over rival Montrose in 2005, part of a masterful 4-6 turnaround.

But, again, despite his best efforts, Susquehanna went 5-25 in its next three seasons. He never gave in. And in 2010, Susquehanna returned to a championship level. The Sabers rolled to a 9-2 record, pulled off an upset at home on the final day of the regular season by beating Old Forge, and captured the Lackawanna Football Conference Division III title.

But, even Bagnall knew, he needed to hand over the program and after the 2011 season and a remarkable career he walked away with a record of 169-129-3.

“He had a great influence on me. He loved football. He showed a belief in his system and nobody in the state ran the veer. He knew it could work if it was run the right way. “He was always giving life advice. He was always offering help. He was a father-figure and an approachable guy.”

— ANTHONY DORUNDA, Susquehanna QB, 2004-05

Dick Bagnall

BLOOD BROTHERS

While calling upon Bagnall to reflect on his coaching career in the spring of 2011, Bagnall mentioned that he couldn’t immediately answer my call because he was on the phone with a dear friend. He went on to describe his long distance bond with Dr. Kim Murphy, who resided in San Antonio, Texas. It was like nothing I had ever heard before and I begged him to let me tell their story.

After some hesitation, because of his enormous humility, he agreed, understanding that the message was too important to keep to himself. It turned out to be the most important story of my career, and one, that I am most proud of writing.

Facing an uncertain future and battling the fear of mortality, Dr. Kim Murphy wanted only a chance to see his 8-year-old daughter graduate high school.

Diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia in 1997, his chances of being in the audience, he admitted, weren’t great. And being a pathologist, the San Antonio, Texas, resident knew the odds were indeed against him.

Then, he received a gift from a guardian angel. Thousands of miles away in the northern reaches of Pennsylvania, longtime Susquehanna High School football coach Dick Bagnall was donating blood, hoping to help friend Tony Aliano, who was also suffering from leukemia and desperately needed a bone marrow transplant.

Bagnall — and many others — did not match. Aliano died in 1999.

After making the donation, the veteran coach’s results went on the national registry, and through a search, he did match — almost perfectly — with someone he only knew as a 43-year-old man with a wife and daughter.

Eager to help, Bagnall endured the process of having his marrow harvested. Murphy received that marrow and had his dream come true, seeing his daughter Marybeth graduate from Texas Military Institute in 2008.

Thirteen years after his transplant, Murphy is cancer-free and is getting ready to see his daughter begin her senior year at the University of Oklahoma.

And he is a miracle of life through the power of bone marrow donation.

“We are blood brothers,” Murphy said recently from his home in Texas. “Dick has been a real champ. Every time I speak with him he tells me, ‘anything I ever need, he’s there for me.’ Knowing that he is there if I need it, is a tremendous source of security and a feeling safety. “There is someone there who has already saved my life and someone who is willing to go to bat for me again. I am so, so appreciative.”

PLEASE CLICK LINK TO READ FULL STORY

BLOOD BROTHERS: Susquehanna football coach Bagnall saved a life by donating his bone marrow

That is Dick Bagnall, the man.

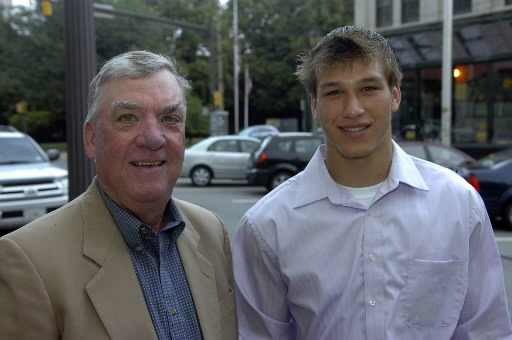

Susquehanna coach Dick Bagnall with former quarterback Dan Kempa.

HALL OF FAME AND BEYOND

As he did for most of his career, Bagnall slipped into retirement and spent his time outside the spotlight. He spent more time with his family, but never changed.

On a rainy night in Susquehanna, on a rare night game at William Emminger Memorial Field, as the hours drew late, Bagnall offered staffer Herb Smith a warm kitchen to write and file his story from rather than the cold of his car.

In 2018, when I called Bagnall to congratulate him on his well-deserved induction into the Pennsylvania Scholastic Football Coaches Association Hall of Fame, he finally, after all the years, broke down. His emotion could be felt through the phone as he struggled to explain what this meant to him. …

“It’s just ‘Wow.’ What an honor for an old coach from Susquehanna High School. It’s just wonderful.”

He is a commanding presence in the Susquehanna Community. He is a Hall of Famer and he is beloved.

And I can’t think of anyone who better defines the award, “Man of the Year.”

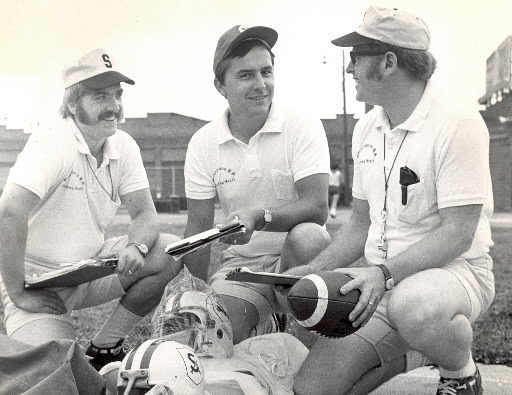

City Head Coach Mike Hemak from Susquehanna is flanked by his assistants, Dan Wolfe, left, and Dick Bagnall.

Joby Fawcett has covered high school sports — including football, girls and boys volleyball, girls and boys tennis, girls and boys swimming, boys basketball, girls and boys track and field, and girls and boys lacrosse — for 22 years. The High School Sports Blog offers deeper insights plus statistical and historical information for fans and features photos, videos and graphics along with Top 5 polls for tennis and volleyball. Contact: jbfawcett@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5367; @sportsTT

Then, he received a gift from a guardian angel. Thousands of miles away in the northern reaches of Pennsylvania, longtime Susquehanna High School football coach Dick Bagnall was donating blood, hoping to help friend Tony Aliano, who was also suffering from leukemia and desperately needed a bone marrow transplant.

Then, he received a gift from a guardian angel. Thousands of miles away in the northern reaches of Pennsylvania, longtime Susquehanna High School football coach Dick Bagnall was donating blood, hoping to help friend Tony Aliano, who was also suffering from leukemia and desperately needed a bone marrow transplant.