Editor’s note: This column discusses mental health and suicide to shed light on how it feels to attempt suicide and to help others understand the recovery process.

If you are contemplating suicide, find help by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, a free, confidential hotline available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. For more information and resources, visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

One of the most amazing things in my life occurred when I started hormone therapy with estrogen. Before then, I felt so numb to any emotion that I honestly thought I didn’t have any.

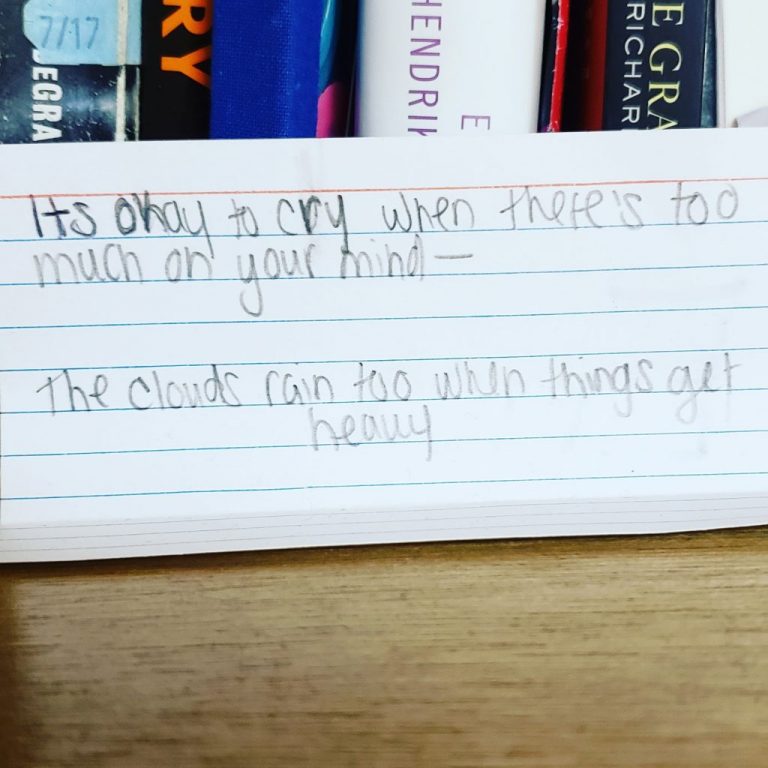

Yet when I started the process, I also began feeling new things: sadness, pain, happiness, love, joy — I had to process and understand all of them. I found myself actually smiling and feeling happy when with people, but then came the downside, where these feelings started unearthing old, hurtful emotions I had buried away for good reason. These overtook me the day I told a mental health delegate I didn’t deserve to live.

A few hours after my delegate took down my story, she came back and asked whether I wanted to voluntarily admit myself to the hospital or have a doctor force admission. I took the voluntary admittance, and my counselor suggested that I stay in a local facility to be close to my school and friends.

That sounded good to me. Seventy-two hours later, I finally was admitted, accompanied by fear and numerous questions. What kind of room would I get? Would they put me in the men’s rooms or the women’s rooms? Would they use my preferred name or my legal name? Would they disagree with me being transgender since “biology said” I was male?

One of the main reasons I ended up in the hospital was because I hated being transgender, and my gender dysphoria — the pain you feel when you recognize that your outside body does not match who you feel you are — was overly sensitive. So every slipped pronoun, use of the wrong name or disregard of my gender compounded the pain and mental frustration. It fed back into the negative, critical voice that had convinced me suicide was the answer.

When I got admitted to Geisinger Community Medical Center in Scranton, it seemed exactly like it does in the movies. Escorted by two big security officers, I felt like I was going to jail as I came to the locked-down mental health ward, terrified out of my mind.

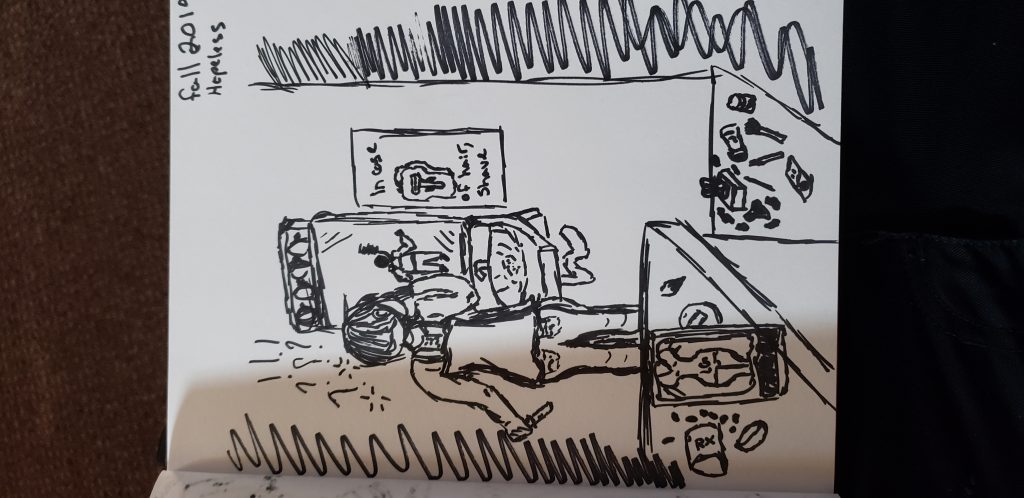

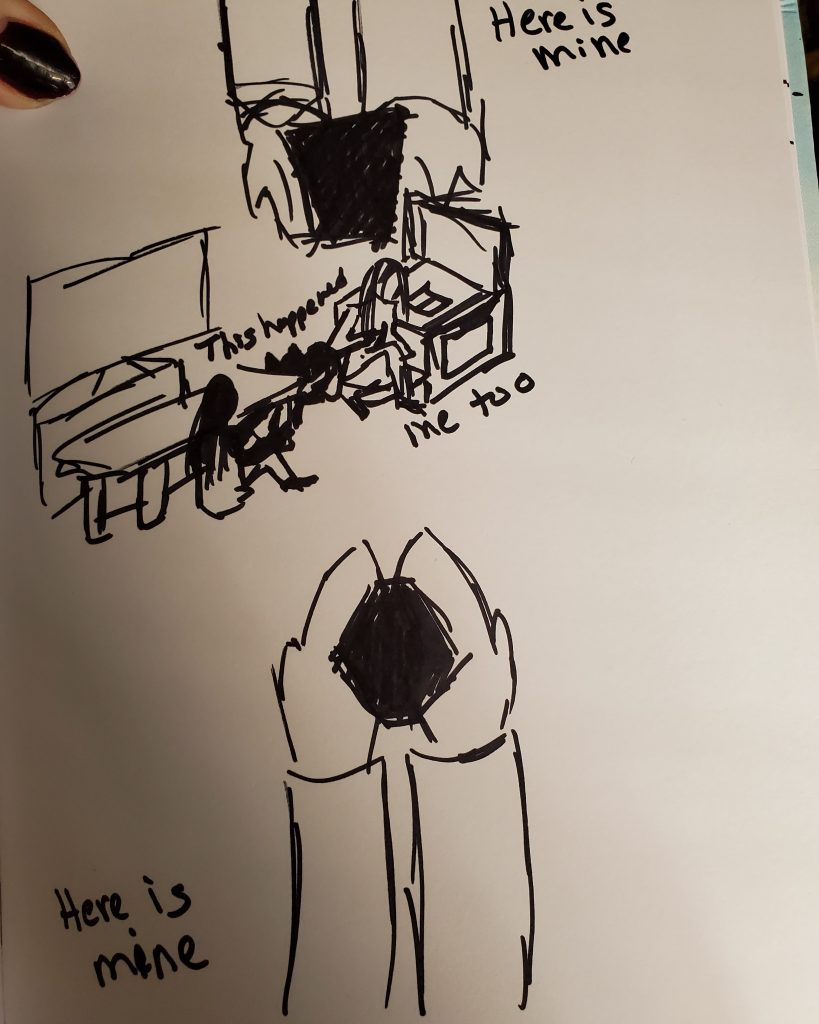

More people are sexually assaulted and abused than we think. Sometimes all we need is someone who understands so we can show them our pain…we dont give it to them because it is ours…but we can show it

Because I was in emotional crisis, my autism symptoms also caused havoc. For autistic people, new places can be terrifying because all the new things can over-stimulate them. I didn’t like being touched or having people around me or crowding me, I rocked back and forth and banged my head, I refused to eat anything but two or three foods, and I didn’t want to talk because I didn’t trust anyone. I took medication, but barely slept. Here I was, a decorated Army sergeant and college graduate reduced to staring off into the distance as others saw me as someone mentally slow and not cognizant.

I met with doctors, counselors and social workers who asked me things I had already discussed, like why I wanted to kill myself, and I didn’t want to relive that feeling. At one point, a doctor thought I was just overly stressed from school, but my “stressed look” actually had resulted from reliving years of emotional and sexual abuse. Thankfully, another medical professional understood the importance of my gender identity and made sure that my name and pronouns were changed and that staff accommodated me.

Every person who poses a suicide risk gets one-on-one help, someone the hospital mandates to sit with you and make sure you don’t hurt yourself. Me being me, I made friends. Many were kind, understanding and curious about me being transgender. Some of the nurses were good about my pronouns — they messed up a few times, but I can’t blame them — and were incredibly kind. They made sure the next shift knew my preferred name and pronouns.

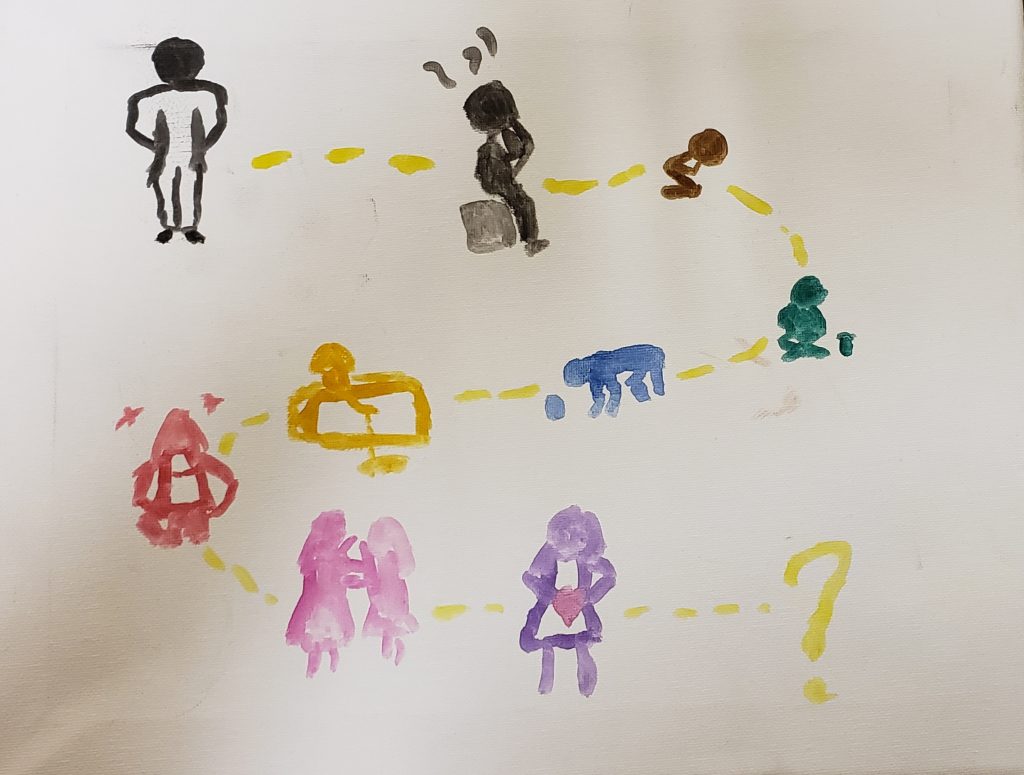

This is my map to finding myself. My art therapist asked me to draw a map to my femininity. So I drew a map!

One nurse, Julie, was a one-on-one person who always had a smile and was incredibly kind to me. No longer on my hormones, I grew facial hair pretty quickly, which brought up feelings of dysphoria and anxiety, and she understood. She let me shave and then she did something that probably seems small, but when your world feels like it’s coming to an end, those small things bring you out of the pain. I only had the lotion and soap the hospital had given me, and Julie grabbed body wash, shampoo and lotion from her gym bag and gave it to me. It not only smelled fresh but more importantly gave me a small link to my feminine identity, which offered a huge sense of comfort.

Of course, there were stumbles. At one point, a mental health tech scolded me for bringing food into my room, a rule violation. I had been allowed to eat in private, however, because my autism makes it impossible for me to do so in front of others. I tried explaining, but she dismissed it. A charge nurse eventually talked with the tech about it, but when she came back to my room later, she brought up how I must have eaten with others in the military. “Are you sure you need this?” she asked. “Are you just making this up?”

This encounter made my anxiety and self-shame skyrocket after I had started to get better over the preceding days. If you work in the mental health field, remember that just because we are patients and are struggling, we aren’t incompetent. And the situation gave no one any right to judge what my own limits and issues were.

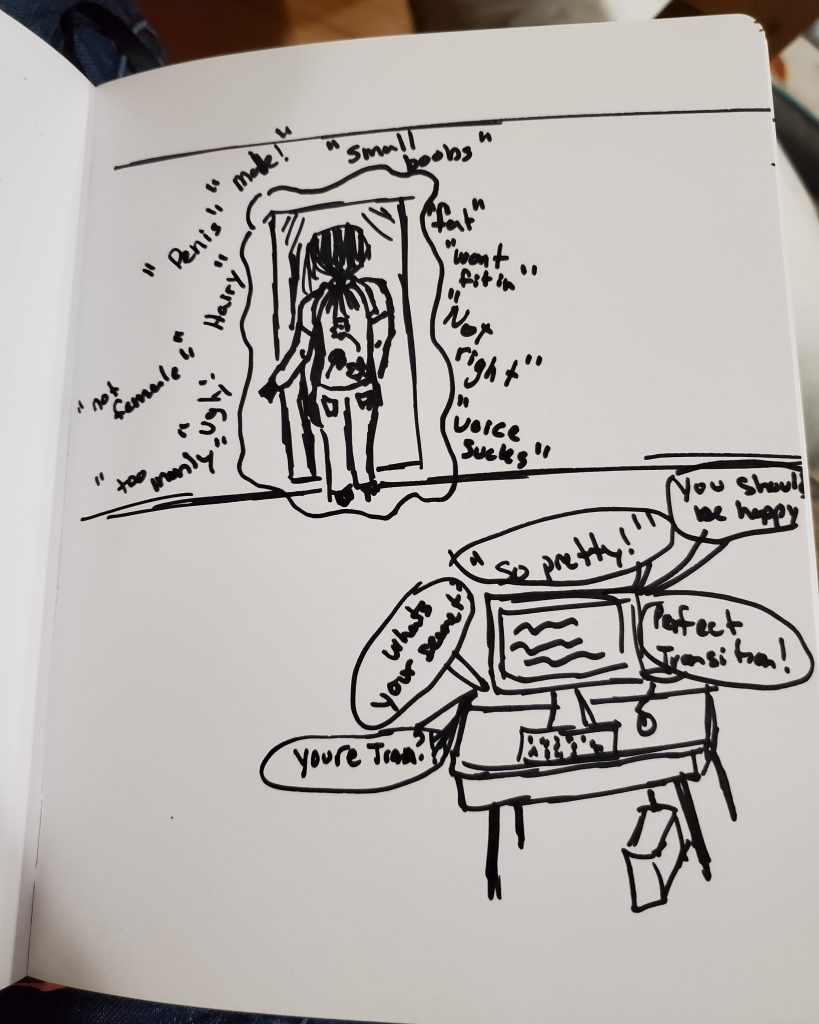

This is now…5 months later. It is strange…I went from being afraid of being too manly to now being asked “what my secret is.” Therapy. That’s my secret.

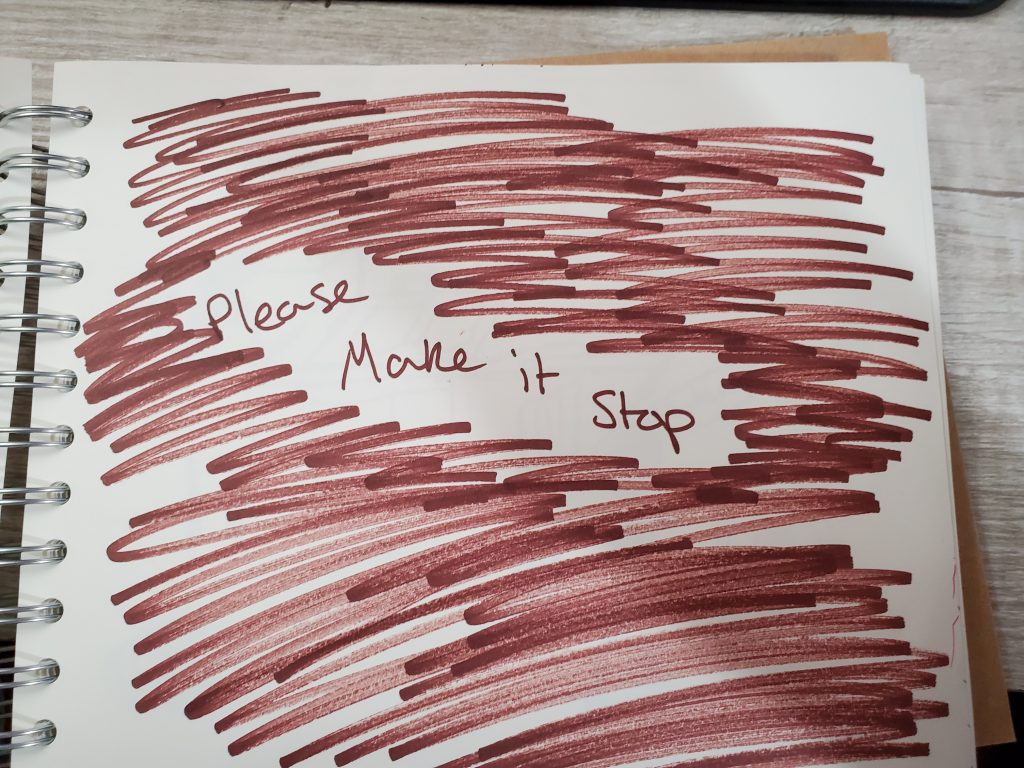

I eventually got to a point where I realized I had three options: lie to the doctor and tell him my suicidal thoughts were gone so I could leave, keep medicating myself until I was so numb I turned into a zombie or figure out my own therapy using the coping skills my therapist taught me.

Choosing the latter, I grabbed a Sharpie and started writing and drawing, beginning with my earliest negative memories. One by one, they came out on the paper. Every time a traumatic memory came up and I drew it, the feeling would go away. This is what got me out of the hospital.

After that, I continued therapy and worked on my issues. I still draw, which helps me turn my feelings into something tangible so my therapist can more easily see exactly what I remember. Then, we can talk about and start processing it.

Recently, my therapist reminded me of how far I have come. Only a few months have passed since my hospitalization, and I have never been that bad again. I have come off the medication they gave me and found healthier outlets for coping.

Trauma never goes away, but the goal isn’t to get rid of or hide it — it’s to come to terms with it so the emotions no longer control you. It comes down to accepting that the trauma occurred, giving yourself some empathy and compassion, and forgiving yourself because it wasn’t your fault.

I forgive myself. It wasn’t my fault. And that’s OK.

A Tunkhannock native, Erica Smith is a 28-year-old disabled veteran, dog mom, transgender woman and graduate of Marywood University, where she earned dual bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and physician assistant studies with minors in history, astronomy and bioethics plus an honors citation. She is a feminist philosopher and a bioethicist (certificate level) who is pursuing a master’s degree in clinical mental health counseling at Marywood and has written two graduate-level theses, “Ethical Medical Treatment for Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria” and “An Ethical Analysis of the Mental Healthcare System Treatment of Gender Dysphoric Patients.” As an advocate for LGBTQIA++ people in Northeast Pennsylvania, she has spoken at events and tries to educate and start conversations on the topic. Additionally, Smith is a volunteer firefighter/EMT and loves reading, playing with her dog, playing video games, building computers, drawing, journaling and spending time with her Christian women’s group, Delight. Contact her at ssgsmith51@gmail.com.