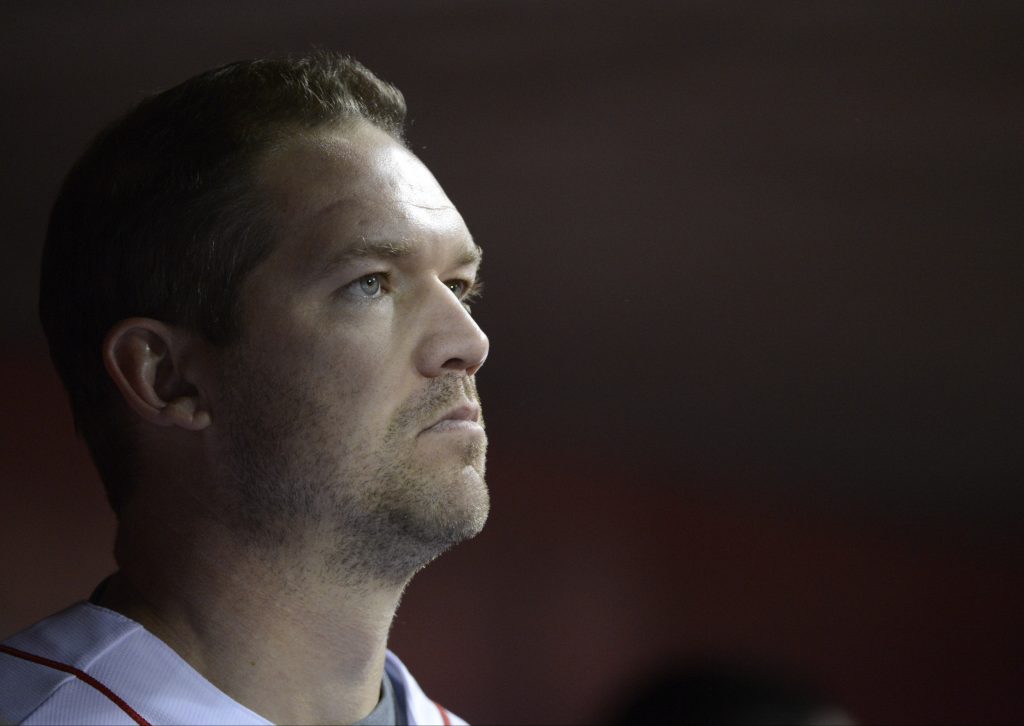

No question, 2019 was a great season for Scott Rolen.

Indiana won the Big Ten regular-season baseball championship, after all. That was Rolen’s job, to

help the Hoosiers do that as their director of player development.

The one-time Red Barons and Phillies standout wasn’t employed last year to pick grounders at the hot corner, or to be a solid middle-of-the-order run producer, as he was for a good portion of his 17 major league seasons. Hasn’t been since 2012, in his defense.

But last year, somehow, he became a much better baseball player.

How do I know? Because that’s what the Baseball Hall of Fame voters are telling us.

According to balloting information tabulated online by the incomparable Hall of Fame ballot tracker Ryan Thibodaux, Rolen is hovering just above 50 percent support among voters who have announced their selections as of late Wednesday afternoon. A player needs to be selected on 75 percent of the submitted ballots to earn induction, so Rolen probably isn’t a threat to earn election this year. But big picture, his numbers in the 2020 voting are a big deal.

Rolen is in his third year on the ballot, and he never made more than a spirited flirtation with getting 20 percent of the total vote. In 2018 and 2019, Rolen got 116 Hall of Fame votes, combined. If he stays on his current pace, he can get 200 or more this year alone.

What possibly could have changed?

We knew 2020 would likely be the first year a player who suited up for Scranton/Wilkes-Barre got to deliver an induction speech in Cooperstown, because Derek Jeter is a lock. Current voting indicates there’s a solid chance for two, since Curt Schilling sits at around 80 percent. Maybe, there even will be a third sneaking in, with Roger Clemens a few tenths of a point above the minimum. Rolen is making a compelling case to someday be the fourth.

This column isn’t going to debate the merits of Rolen’s candidacy. It’s to ask this question: Should a player be counted among the best to ever play the game if he needs so much time to build a consensus?

Inconsistent values

Six years ago, just one out of 10 voters thought Larry Walker was Hall of Fame worthy.

Eighteen players in 2014 voting received more votes than the former Rockies slugger, who has nearly 85 percent of announced votes this year and is on track for induction. Twelve of them have since been inducted into the Hall of Fame, and if Barry Bonds, Clemens and Schilling get in, that number will shoot to 15.

But that summer, just three players — Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine and Frank Thomas — were inducted.

Guys like Mike Piazza, Craig Biggio, Jeff Bagwell, Mike Mussina and Edgar Martinez all had to wait even though they were inducted with relative ease in future voting. For what it’s worth, 16 players received more votes than Rolen in 2018, when he got just 43 in his first year on the ballot.

Bottom line is, you’re either a Hall of Famer when you’re first eligible for induction, or you’re not. But the voting process doesn’t make that likely, or even possible.

Vote for more

Voters are asked to pick no more than 10 players per ballot, which is the big problem here. They often complain about feeling constrained by the process, leaving players off their ballots for whom they’d otherwise vote. You also have voters who will select 10 players no matter what, which makes players on the ballot longer more attractive as the years pass.

Being a first-ballot Hall of Famer is a special, but when you’re talking about honoring the best to ever play, there should only be first-ballot Hall of Famers. The voting process should be changed to increase the amount of first-ballot Hall members and reduce the amount of time players are on the ballot.

Doing so would be relatively simple: Eliminate the cap on the number of players a voter can select in a given year; five years between retirement and eligibility is plenty of time to debate a candidate’s merits, anyway. Any player who gets 75 percent of the vote — whether it’s one or 15 — is inducted. Any player who gets 50 percent can stay on the ballot a second year, and they can get a third year if they get 60 percent in their second go-round. Everybody else is out, their induction at the mercy of the veterans committee down the road.

Induction should be reserved for the very best of the best, the no-doubters who consistently have overwhelming support. It shouldn’t be about a years-long parsing of numbers, spirited internet fan campaigns or the most creative argument that can be backed by obscure metrics.

Baseball greatness shouldn’t be that difficult to judge, after all. You know it when you see it.

Donnie Collins has been a member of The Times-Tribune sports staff for nearly 20 years and has been the Penn State football beat writer for Times-Shamrock Newspapers since 2004. The Penn State Football Blog covers Nittany Lions, Big Ten and big-time college football news from Beaver Stadium to the practice field, the bowl game to National Letter of Intent Signing Day. Contact: dcollins@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5368; @DonnieCollinsTT