BY LAURIE HERTZEL, MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

In 1969, when he was 22 years old and slogging through the jungles of Vietnam, land mines in front of him, snipers behind him, Tim O’Brien was certain every day that he was going to die.

He wrote only a few letters home because “I didn’t know how to put a good face on it all, and I didn’t want to lie,” he said in a recent telephone interview from his home in Austin, Texas. He did some other writing in Vietnam, publishing a couple of harrowing dispatches in the Minneapolis Tribune and keeping a notebook, “little scribbling notes about stuff. Most of them got mildewy and wet and disintegrated. But I did have a couple of readable pages when I came home.”

Those pages became part of his first memoir, “If I Die in a Combat Zone,” published in 1975 and steeped in death and dread. He wrote in the book’s afterword that it was intended to read like “a document of the sort that might be discovered on the corpse of a young PFC, a Minnesota boy, a boy freshly slaughtered in Quang Ngai Province in the year 1969.”

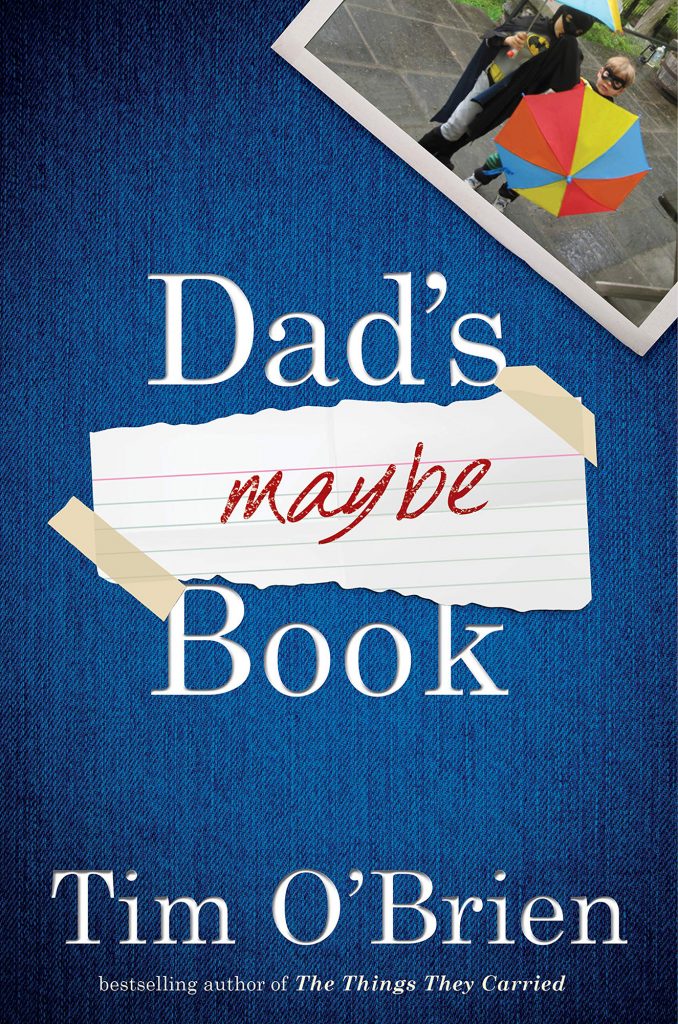

Now 50 years and seven novels later, O’Brien has written a second memoir — one that is, again, suffused with awareness of his own mortality. The new memoir, which has the cheerful, slightly goofy title “Dad’s Maybe Book,” is, like the first one, written as though it will be read posthumously — in this case, by his sons, Timmy, 16, and Tad, 14.

O’Brien is 73, and although he is in good health, he knows he will not live long enough to witness much of his children’s lives. This book is meant to keep him alive in their minds after he is gone; it’s packed with stories, memories, suggestions, reading assignments, a few family snapshots and a little advice.

This preoccupation with his own death is familiar ground for him.

AMAZON / SUBMITTED PHOTO

“Dad’s Maybe Book” by Tim O’Brien

“It reminds me a lot of when I was younger in Vietnam and I thought I was going to die and resigned myself to it,” he said. “I went through it when I was young, and now I’m going through it for good.

“We all have to face our own mortality. For me the problem is having these two young kids who one day are not going to have a father, and that’s not good. So I’m doing what I can through this book, saying to them things that I would say if they were 21, or 31.”

For most of his life, O’Brien did not want children. His own childhood wasn’t particularly happy — his father was often drunk, and his parents quarreled frequently, late-night shouting matches that started with cruel words and ended, he said, with days of brittle silence.

And O’Brien — the author of nine books, including 1990’s “The Things They Carried” and the National Book Award-winning “Going After Cacciato” (1978), both set during the Vietnam War — was protective of his time, requiring 10 or 12 hours each day of quiet and solitude in which to write.

“A father’s chief duty is to be present,” he said, and he didn’t think that if he had children he would be present. And so 20 years ago when his girlfriend, Meredith, broached the topic of children, O’Brien said no.

The two broke up. And then they got back together, just to talk. They opened up about their lousy childhoods, and their hopes for the future. “I realized I wanted a happy family life, too,” O’Brien said.

They married. They had Timmy and Tad. And O’Brien was present. But he also stopped writing.

Pingpong and memories

O’Brien’s last book, a novel called “July, July,” came out in 2002. Timmy was born a year later. Tad came along two years later. By then, O’Brien was 60. For the next eight or nine years, he hardly wrote at all. He was very busy, he said, “not being an author.”

He was busy changing diapers, ferrying his boys to school, driving them to games, reading to them, telling them stories, playing pingpong and football and basketball.

The age gap weighed on him from the beginning. “I feel like my days are numbered with my kids,” he said. “And with each passing hour, time gets less. I feel in the remaining time I want to compress all the love I can.”

In 2004, he started jotting down notes to his sons — letters and reading suggestions and memories. He had not intended this very personal collection of scraps and thoughts to become a book, but his younger son thought otherwise. “Tad said, ‘You should make this a book. Maybe other kids would like to read it, other parents.’ And it was then that I sort of thought, maybe, maybe. It was always maybe.”

“Dad’s Maybe Book,” named by Tad (who asked his dad if he might get royalty payments for the title) is at times a profound and moving remembrance of O’Brien’s childhood in Worthington, Minn., his service in Vietnam and his thoughts on writing and writers (primarily Ernest Hemingway). At other times it is a tender and hilarious recounting of the first years of his sons’ childhoods — childhoods that O’Brien is determined will be as different from his own as possible.

His town sent him to war

O’Brien was born in Austin, Minn., and a few years later moved with his family to Worthington, the Turkey Capital of the World, where his father sold insurance.

“My dad was just a great guy, well-read and sophisticated in ways you do not expect of someone living in Worthington, Minnesota,” O’Brien said. “He had a great sense of humor. He loved children — children really loved him. All my friends thought he was the best guy on Earth. I wasn’t sure he liked me very much, probably because he was drunk a lot. I idolized him, but I was also a little afraid of him.”

His memories of Worthington, he writes in the new book, “are colored as much by what went on with my father — his increasing bitterness, the midnight quarrels with my mother, the silent suppers, the vodka bottles hidden away in the garage and basement — as by anything having to do with the town itself. I began to hate the place. … The water tower overlooking Centennial Park seemed censorious and unforgiving. The Gobbler Cafe on Main Street, with its crowd of Sunday diners freshly invigorated by church bells, seemed to hum with rebuke.”

And then in 1968, shortly after O’Brien graduated from Macalester College in St. Paul, Worthington sent him to war.

In those years before the draft lottery, hometown draft boards decided which young men would be drafted. Draft boards had a quota to meet and not a lot of oversight. According to the U.S. government Selective Service website, “there were instances when personal relationships and favoritism played a part in deciding who would be drafted.”

O’Brien has no idea why he was drafted and others from Worthington weren’t, but personal relationships and favoritism sound plausible to him.

“I was eligible, and I was chosen,” he said. “I never found out the mechanics of how they decided who would go. I know a lot of people weren’t drafted who were eligible. My dad thought back then it was probably because we were not native to Worthington, but that’s pure speculation.”

O’Brien was opposed to the war, and he writes bitterly in “Dad’s Maybe Book” about being drafted. “One father chose another father’s son to go off to the other side of our planet and kill people and maybe die,” he writes. “How monstrous, I’d once thought. How monstrous, I still thought. Circle the name of your own darling son. Circle your own name.”

But O’Brien’s name was circled, and during basic training in Washington state he contemplated slipping over the border to Vancouver, contemplated starting a new life in Sweden. In the end, he said, he was too cowardly — his father was a World War II vet, his mother had been a WAVE, the town of Worthington was small, and he could not bring himself to defy and disappoint them all.

“It’s one of the bitter ironies of my life that something I despised so much and terrified me so much made me a writer, made me have to write,” he said. “It’s kind of ironic that the worst thing that ever happened to me determined a lot of the rest of my life.”

When he returned from Vietnam, O’Brien worked briefly for the Met Council in the Twin Cities and then headed north. “I decided the war really was still in my throat,” he said. “I can’t say I was dreaming or panicked or desperate; I don’t think I had post-traumatic stress syndrome.

“I think I was bewildered. Why am I still alive? It seemed impossible that I could have done the stuff I did and still be living.

“And all the memories of the dead people and the wounded and the guys without legs — it just seemed shocking. Why, why was I there? And I just quit the job and took off for Madeline Island, where I just slept on the beach. Listened to the radio in my car. I can’t say I was in any great pain. I was mainly just bewildered.”

At night he scooped out a shallow trench on the sandy beach for his sleeping bag. “I’m still scooping out a trench each night,” he writes. “The trench is how I get by. In imagination, after the lights go out, I transform my bed into a shallow hole in the earth. I string barbed wire, emplace machine guns, put out the claymore and trip flares. … Some people lock their doors at night. I lock the doors in my head.”

Writing at 3 a.m.

“Dad’s Maybe Book” opens when Timmy is a newborn, but it does not progress chronologically from there.

“Memory does not work chronologically. Never has and never will,” O’Brien said. “There’s my dad when he’s a young man, there’s my dad in his coffin, there’s my dad throwing me a baseball, there’s my dad drunk, there’s my dad being funny. It’s not chronological, and it’s probably why I’ve never written a linear book — I don’t know how to do it because my brain doesn’t work in a linear fashion.”

Because of this episodic structure, the themes of “Dad’s Maybe Book” are braided together and repeated over and over. His love for his sons; his complicated feelings for his father; his grief at the knowledge that he will not live to see his boys become men; his abhorrence of war; his sense of his own mortality.

Despite these dark themes, O’Brien said, he doesn’t think about the war constantly, nor does he dwell on death. “I think, like all of us, we forget it. I forget it,” he said. “I don’t think about it every instant.”

He wrote the book mostly in the middle of the night, getting up at 3 a.m. to work.

“The world is quiet, you’re close to your dreams, you’ve just gotten out of bed, you can work in your underwear,” he said. “It was really a productive time. Not only that, it was a mysterious kind of wonderful feeling, so many thoughts that bounced through my head, those early-morning thoughts.”

Now that the book is finished, he continues to get up at 3 a.m., continues to listen to those thoughts.

“I must say, just this morning, early on — I’d had an idea that I’d written maybe 20 pages on, 15 years ago,” he said. “But I got stuck on: Why write it? What passion do I have for this story? And I didn’t know the answer to it and so sensibly I stopped.

“But this morning, 3 in the morning, I’m doing dishes, an idea came to me. And I’m going to probably see where it takes me.”