BY MOIRA MACDONALD, THE SEATTLE TIMES

Reading knows no season. But fall always feels like an opportunity to really settle in with a book, as the days get shorter and the winds cooler. Here are 10 new titles that I recently curled up with; some of them were authors previously unknown to me; others were old favorites whose latest works I have happily anticipated. All had one thing in common: I couldn’t put them down. Happy fall!

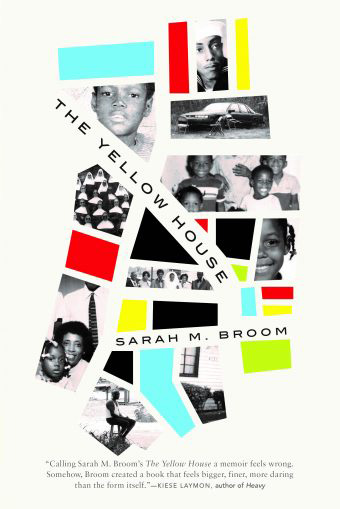

‘The Yellow House’

By Sarah M. Broom (Grove Press, $26)

“The Yellow House was witness to our lives,” writes Sarah M. Broom in her remarkable memoir. “When it fell down, something in me burst.”

Many years in the making — Broom notes in the acknowledgments that she signed a deal to write it in 2005 — “The Yellow House” is the beautifully written story of a place, and of the lives that flowed in and out of it like a river. In 1961, Broom’s mother, Ivory Mae, then a very young widow with small children, bought a weary, modest shotgun house on Wilson Avenue in New Orleans East for $3,200; money from her late husband’s insurance policy. She remarried and raised a total of 12 children and stepchildren in the house over the years; the youngest was Sarah, who grew up gazing around the neighborhood and the city with a writer’s eye.

That narrow house at 4121 Wilson no longer stands; badly damaged by the floods that followed Hurricane Katrina (“Water will find a way into anything, even a stone if you give it time”), it was demolished by the city. But it lives in these pages — in the jostle of children in its rooms, in the stories of an ever-shifting mosaic of neighbors, in the portrait of a part of New Orleans that’s far from tourists (“Walkers here did not stroll”), and in the vivid, poetic voice of a woman learning the meaning of home. “Houses provide a frame that bears us up,” Broom muses, on her childhood home’s destruction. “Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house.”

‘Who Are You, Calvin Bledsoe?’

By Brock Clarke (Algonquin, $26.95)

Brock Clarke’s new novel owes an affectionate debt (one the author acknowledges in an endnote) to Graham Greene’s “Travels with My Aunt”; it’s the story of a lost, middle-aged man whose life gets an upheaval thanks to the arrival of his previously unknown aunt, who whisks him off on a trip to Europe. That man, Calvin Bledsoe (he was named for his mother’s favorite theologian), works as a blogger in the pellet-stove industry, has an ex-wife named Dawn who isn’t very nice, and in the book’s opening scenes has become a 49-year-old orphan after his mother dies in a bizarre accident. Enter, at the funeral, Aunt Beatrice, who has a missing front tooth and a way of sweeping her nephew into adventure, whether he wants to or not.

Clarke, author of “An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England,” has a playful gift with words: Aunt Beatrice “sat at the wheel, fuming. For the first time, I fully understood that verb. It was as though her anger was a gas, and I could smell the fumes.” The book has the feel of a manic pile-on — there are perhaps a couple too many madcap characters and hairpin-turn plot twists — but enjoyably so. At its heart is a man looking for a life a little bigger than the one he’s got — and finally daring to find it.

‘Marley’

By Jon Clinch (Atria Books, $27; on sale Oct. 8)

“Marley was dead, to begin with,” is the famous opening sentence from Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” efficiently dispensing with Ebenezer Scrooge’s former business partner (the flesh-and-blood version of him, anyway; he turns up as a ghost later). Now Marley gets a whole novel, from a skilled author who’s entered the backstory-of-literary-characters realm previously: His debut, 2007’s “Finn,” told the backstory of Huckleberry Finn’s father.

And it’s a good one; told in alternating chapters from the perspectives of Marley and a younger, less bitter Scrooge and ranging from 1787 (when the two meet at the appropriately named Professor Drabb’s Academy for Boys, filled with boys who “looked like old men long denied nourishment”) to Marley’s deathbed in 1836. Clinch has fun with Dickensian names, but mostly this is a tragic tale of a young man slowly hardening into stone, and of a familiar character’s outline being filled in with new, darker colors. “Five-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, rising from his little bed with the strains of some symphony bursting within his brain, was never more thrilled by the spontaneous act of creation than is Scrooge by these enchanting numbers,” Clinch writes, of Ebenezer at work. “The realities they represent — casks of rum, bolts of cloth, the hides of enslaved men — are nothing to him. He cares only for their music.”

‘Dominicana’

By Angie Cruz (Flatiron Books, $26.99)

It’s been a 14-year wait for Angie Cruz’s latest novel (her most recent work was 2005’s “Let It Rain Coffee”), and “Dominicana,” a coming-of-age story of a young immigrant from the Dominican Republic, has a richness that comes from long simmering. In its early pages, it’s 1965, and 15-year-old Ana leaves her rural home — “ … where we live, there’s nothing but dark. Not a house for at least a mile. And the electricity always in some kind of mood.” — to marry the vaguely dangerous-seeming Juan, who is twice her age and drinks a lot. Ana, in her heartbreaking innocence, imagines that her New York life with Juan will be glamorous, full of shopping and parties and dancing in nightclubs. It is, as the reader guesses before Ana does, not like that at all.

Told in first person, in an unadorned voice both childlike and wise, “Dominicana” takes us inside the mind of its very young narrator. We experience that lonely Washington Heights apartment, which smells “at best, like wet cardboard, at worst like something dead,” with her — and travel in her mind, as Cruz elegantly shows us how Ana, whenever she closes her eyes, is home again. And a small miracle happens in the book’s pages; not quite a happy ending, but the emergence of character who wasn’t there before. By the novel’s end, it’s Ana but not Ana, a woman bravely setting forth on a new life, finding and conquering America on her own newly learned terms, and facing a future as hopeful as an infant’s bright eyes.

‘Twenty-One Truths About Love’

By Matthew Dicks (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99)

This book was a wild card that I plucked off a pile — Dicks has written three previous novels, including the bestseller “Memoirs of an Imaginary Friend,” but I wasn’t familiar with any of them — and it’s definitely High Concept. It’s the story of a regular guy named Dan facing trouble at work (he owns a bookstore that’s rapidly draining money), in his marriage (he can’t shake an obsession with his wife Jill’s first husband, who is dead), and his soon-to-be-expanding family (the arrival of their first child is imminent). And it is told, entirely, in lists. As in: to-do lists, goal lists, things-I-learned-today lists, things-spoken-by-coworkers-today lists, reasons-why lists, etc. (For the record, I have nobly resisted the urge to format the previous sentence as a list.)

And darned if the gimmick doesn’t work, at least for a while. Dan is both a sad sack and a charmer: We learn that he bought the bookstore because he hoped it “would make me less ordinary”; that he dislikes Ethan Hawke, “people who talk about alcohol like it’s an interesting topic” and Etch A Sketches; and that he thinks of himself as “an unfunny David Sedaris.” And while things run out of steam midway through — this 341-page novel could stand to be about a third shorter, as the list format increasingly gets tired — I nonetheless persevered to the end, wanting to be sure things would work out OK for Dan, of whom I’d become rather fond. A quick, light read, and an unexpected pleasure.

‘Akin’

By Emma Donoghue (Little, Brown, $28)

The Irish-born writer Emma Donoghue has an uncanny way of writing about children: “Room” (later an Oscar-nominated film) told a story of horror from the innocent voice of a small boy, who saw only what his loving mother let him see; “The Wonder,” her most recent novel, introduced us to an 11-year-old who reportedly hasn’t eaten for months, a quiet angel who nonetheless seems like a very human girl.

The child in “Akin” is a departure for her: a surly preteen New York boy named Michael, who through a series of catastrophes has no one to look after him but an elderly great-uncle, Noah, a retired professor and widower living on the Upper West Side. The two have never met before, but (rather implausibly) head off on Noah’s long-planned visit to his hometown of Nice, France, where he hoped to figure out some stories about his mother’s wartime years.

Much of “Akin” is Michael and Noah struggling to coexist, which at times becomes less than engaging; Michael, a troubled child, acts out a lot, and the childless Noah has no idea how to respond. (It was, he notes, “like traveling with a bag of bananas he had little chance of delivering unbruised.”) And the mystery of Noah’s mother never quite finds its feet. But Donoghue is such a fluid, lovely writer that even her lesser books are a pleasure; I found myself quite caught up in the journey to Nice, hoping against hope that somehow these two could find a way to connect. And, as always, Donoghue’s quite poignant on the idea of home — as both a place and a person. Though Michael and Noah are alien to each other, Noah reflects, they were, “in an odd way, akin.”

‘A Nearly Normal Family’

By M.T. Edvardsson, translated by Rachel Willson-Broyles (Celadon Books, $26.99)

Sometimes, you read a book because you want to have a transformative literary experience. And sometimes, you just want to jump onto a roller coaster and go for a ride, knowing that you won’t take a breath until it’s over. This legal thriller, from a Swedish author making his U.S. publication debut, was another wild card for me; I picked it up and started reading, knowing nothing of its provenance — and went for a ride that didn’t end until quite late that night. Told in three sections — father, daughter, mother — it’s the story of a perfectly ordinary family whose life changed instantly when teenage daughter Stella is arrested and accused of a violent murder. The book races us through the accusations, the legal machinations, the toll on the family, and a carefully doled-out flashback to what really happened on the night in question.

Edvardsson tells much of the story through dialogue: short, punchy talk, the kind you can imagine actors tossing at each other in a sleek and just-good-enough Hollywood film. Stella’s parents are Adam, a pastor, and Ulrika, a lawyer — their professions are key here — and both of them immediately spring to their beloved only child’s defense. Can it ever be wrong, Adam wonders, to protect your own child? Is it possible that your child isn’t the person you think she is? What comes first — your family, or your principles? When “A Nearly Normal Family” is over, you feel a little deflated — like you’ve had a little too much of something that isn’t good for you. But you definitely feel like you’ve been somewhere.

‘The Liar’

By Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, translated by Sondra Silverston (Little, Brown, $27)

“Guilt, when it comes to visit, can choose from any number of routes. It can suddenly appear from behind and sink its talons into your back. It can charge you head-on. But Nofar’s guilt, like a Persian cat, rubbed her legs fleetingly, sat for a brief moment on her lap, and moved onward.”

I slipped into “The Liar” like falling into a velvet milkshake; Israeli author Gundar-Goshen’s writing, as illustrated in the passage above, is rich and delicious. Its story is familiar yet riveting: A teenage girl — an ordinary girl, one who works in an ice-cream shop and worries about pimples and wishes she were part of the popular clique at school — tells a lie; one that turns out to have big consequences.

While Gundar-Goshen paces it like a thriller, you read “The Liar” for its playfulness — a girl’s laugh is “round and orange, like apricots”; summer “came to the city, had its merry, sweaty way with it” — and for its wisdom about truth and lies and guilt. Nofar, “drowning in her ordinariness,” needs the lie to make her bigger, brighter, but she fears being found out. “Children always find out. Perhaps, like whales, they possess a kind of sonar that calculates the distance between the story and the facts. The word ‘liar’ is whispered, then spoken, then shouted across the yard. In the end, it is hung around the child’s neck, like a collar.”

‘Heaven, My Home’

By Attica Locke (Mulholland Books, $27)

Last year, Attica Locke won the prestigious Edgar Award (honoring the best in crime fiction) for “Bluebird, Bluebird,” an intoxicating read that marked the debut of Darren Mathews, a black Texas Ranger with a complicated past and a love/hate relationship with his home state. Now, not soon enough, Mathews is back in “Heaven, My Home,” and things aren’t any easier for him: His marriage, to lawyer wife Lisa, continues to be troubled; his not-especially-maternal mother is blackmailing him, for reasons having to do with the crime explored in “Bluebird, Bluebird”; he drinks more than he should; and his lieutenant wants him to investigate a missing child in a rural area in a vast lake — whose family has ties to criminal white supremacists.

Like its predecessor, “Heaven, My Home” is a nuanced, moody and artful tale, centered on a flawed yet utterly real hero whose actions often aren’t heroic. Locke deftly weaves a story thick with characters and conflicting motivations, in language that’s sometimes startlingly lovely. Around that island on that enormous dark lake is a ring of cypress trees, “their trunks skirted so that they appeared like shy dancers at a church social, leaving enough space for God between them …” And Mathews, making his way through the complex thicket of his life, thinks poignantly about the idea of home in the language of blues, which gives this book its melancholy rhythms. “(E)ven in the house where he’d grown up, home was always a reach back in time, glassed as it was in memory. It was still an idea he couldn’t exactly touch. Fodo could sometimes reach it, a pot of peas and ham hocks on the stove. Stories too. But music did it every time. Texas blues were the way home.”

‘The Grammarians’

By Cathleen Schine (Sarah Crichton Books/FSB, $27)

I have, in my own life, the great and unusual pleasure of a close friendship with a pair of identical twins (hi, Katy and Amy!), so I was intrigued by the premise of Cathleen Schine’s latest, “The Grammarians,” about a pair of redheaded, identical twin sisters who share a love of language and grammar. Laurel and Daphne grow up as “two little Professor Higginses,” obsessed with words and “My Fair Lady” and speaking their own special twin language. As adults, they make their way to Manhattan in the 1980s: Daphne becomes a grammar columnist known as the People’s Pedant; Laurel is a teacher who finds her way, like coming home, to becoming a writer.

Written with Schine’s trademark sly sweetness (her books always feel, to me, like Nora Ephron movies), “The Grammarians” is a pleasant meander through two not-quite-conjoined lives. (“My sister is me if I were different,” concludes Daphne, accurately.) What makes it delicious is its playfulness with language: the definitions from Samuel Johnson’s “A Dictionary of the English Language” that open every chapter; the young twins figuring out what words they liked best (among those collected by Daphne: fugacious, oxters, aposiopesis, turgid); the sparkle of the conversations. And I paused for a while over Laurel’s description of her young daughter’s development, saying she wanted to be present “to hear Charlotte pulling the world toward her, word by word.”