BY ERIN NISSLEY, STAFF WRITER

As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise in Pennsylvania and across the world, some lifelong locals might recall other pandemics that swept the region over the last century-plus.

Most are familiar with the Spanish flu that swept Scranton in 1918, sickening thousands and killing hundreds. As the number of cases grew, city officials issued orders to close schools, saloons and theaters and canceled public meetings. Weeks later, Dr. S.P. Longstreet, Scranton’s public health director, halted the sale of alcohol and beer at all restaurants and hotels in the city. Thousands of homes were quarantined, and several large buildings, including the 13th Regiment Armory, were turned into emergency hospitals to treat the cases.

The flu wasn’t our area’s only brush with outbreaks of contagion.

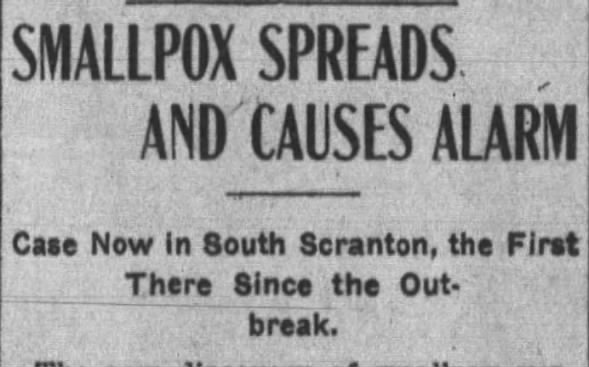

Smallpox

The region’s first recorded brush with smallpox — a contagious, often deadly disease whose main symptoms included rash and fever — came in 1777. The first case was traced back to a Wilkes-Barre man who became infected in Philadelphia. It was not clear exactly how many died.

A bigger outbreak struck in 1903, according to a May 16, 1971, Scranton Times column by Edward J. Gerrity. Officials shut down schools, churches, theaters and other public spaces and had them fumigated to help stop the spread. In addition, public health officials began an ambitious campaign to vaccinate Northeast Pennsylvania youth to halt the disease.

“Hospitals threw open emergency centers where teams of medical men and nurses labored to throw a protective measure over thousands of youngsters,” Gerrity wrote. “One of the busiest hospitals was Hahnemann, where for several days there were long lines of students (waiting) to get inoculations.”

Meanwhile, Taylor physician John W. Houser led the efforts to treat smallpox patients locally. An emergency hospital opened on West Mountain to accept smallpox patients.

Smallpox outbreaks, although not as widespread or as deadly, hit Northeast Pennsylvania again in 1919 and 1947.

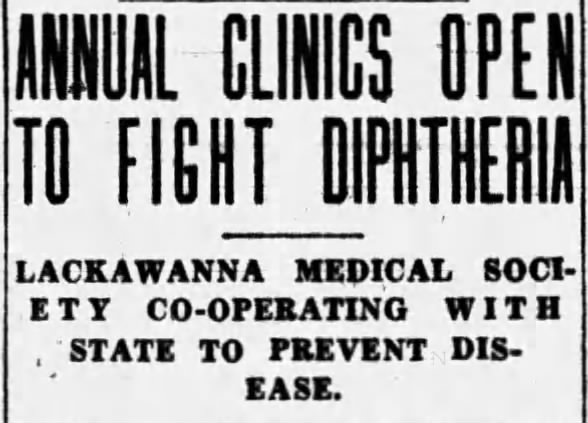

Diphtheria

Several outbreaks of diphtheria hit the city in the 18th century.

Bacteria that cause diphtheria can attach to the lining of the respiratory system, causing weakness, sore throat, fever and swollen glands. If the bacteria get into the blood stream, they can damage the heart, nerves and kidneys.

The first recorded diphtheria outbreak hit Jermyn in January 1946, according to Scranton Times articles.

By Jan. 4, three children had died, all of them under the age of 9. Schools were closed and fumigated, and health officials told parents to keep their children quarantined.

“This is the worst epidemic here in many years, and 20 cases have already been reported,” the Jan. 4 article read.

A similar outbreak occurred in 1944, mostly focused on residents at the Friendship House, 200 Adams Ave. At the time, the facility served as an orphanage/foster home, as well as a home for the elderly.

“Ten new cases of diphtheria” among patients at the home, “and one among employees of the institution were reported by Health Department authorities today as administration officials, armed with a $5,000 emergency appropriation voted by council … rushed plans for the expansion of facilities at the Municipal Hospital on East Mountain,” an Oct. 31, 1944, Scranton Times article reported.

Over the next several days, diphtheria ripped through the Friendship House, infecting a total of 26 residents and employees by Nov. 1, 1944, a Scranton Times article reported. That included a 4-year-old who died; the newspaper reported the little girl was also suffering from pneumonia. Most of the rest of the diphtheria cases from the Friendship House were considered mild.

Several other cases were reported in and around Scranton, too, straining the resources of the Municipal Hospital, according to the article.

“The diphtheria situation here today attracted the attention of major officials of the State Department of Public Health at Harrisburg,” the story reported.

Dr. J. Moore Campbell, deputy secretary of health, remarked that Scranton’s situation was unusual and the number of cases “much too high for today, when we don’t have much of the disease,” according to the story. “He pointed out that in 1943, only 464 cases of diphtheria were reported in Pennsylvania’s 67 counties.”

By Nov. 3, 1944, health officials declared the diphtheria danger in Scranton was waning.

Next week, Local History will take a look at other outbreaks in the region’s history, including typhoid fever and measles.

Typhoid Fever

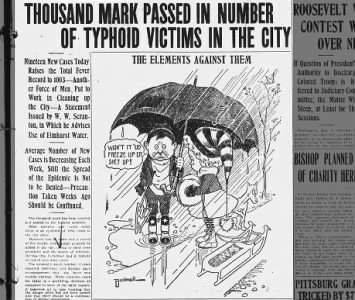

Tue, Jan 8, 1907 – 1 · The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Tue, Jan 8, 1907 – 1 · The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

As typhoid fever ripped through Scranton in the early 20th century, no one could agree on what was causing it or even if there was an epidemic.

But 27-year-old Alice O’Halloran, a recent graduate of Philadelphia General Hospital, can be credited with helping the city get a handle on the number of cases.

With the growing number of cases of the coronavirus here in Northeast Pennsylvania and around the globe, Local History is taking a look back at other pandemics that swept the region. Last week’s column focused on Spanish flu, smallpox and diphtheria. This week, we’ll look at typhoid and the measles.

Door to door

The Scranton Times was instrumental in publicizing a typhoid fever epidemic that began around December 1906, according to a column published March 23, 1967.

The city’s water supply was blamed for spreading the disease, characterized by a high fever, weakness, abdominal pain and cramping, mild vomiting and a skin rash. The head of Scranton Gas & Water Co., W.W. Scranton, denied any problems with the water. Even so, health department officials ordered a cleanup of the city’s watershed.

A city official also denied an epidemic was even occurring, according to the 1967 column. After The Scranton Times published a story quoting a West Scranton pharmacist “that, from the type of medicine many local doctors were prescribing for patients taken suddenly ill, he was led to believe that there were many cases of typhoid fever here,” the city’s director of public health “entered a strong denial, saying that only two cases … had been reported in a month,” the column recounted.

Then-Mayor J. Benjamin Dimmick contacted the state commissioner of public health, who sent O’Halloran to Scranton to take over nursing services in the city. She threw herself into solving the public health crisis, working 18- and 20-hour days to get ahead of the illness.

“She and several other nurses sent here (by the state) joined with nurses in the Scranton area in setting up an organization,” the column reported. “The city was divided into districts and Miss O’Halloran visited practically every home where there was sickness.”

By the time the epidemic wound down, in February 1907, Scranton had 1,141 reported cases of typhoid fever, 108 of which proved fatal.

O’Halloran went on to serve as chief of the state health department’s nursing services. On subsequent visits to Scranton, she recalled how much faith Dimmick placed in her.

Several other typhoid fever epidemics swept the region in the early 1900s. But as a vaccine against it became more common and the cleanliness of water sources improved, those outbreaks became less and less common.

‘Epidemic of measles’

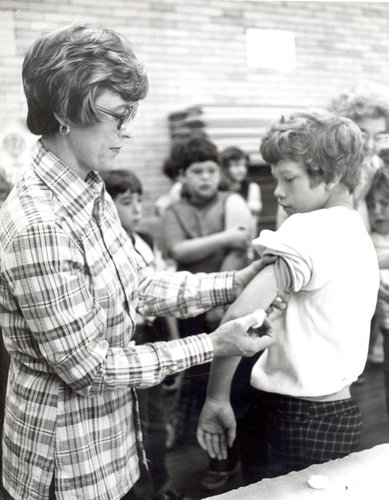

- TIMES-TRIBUNE ARCHIVES Jeff Leas receives some encouraging words from Helen Fawcett, medical clerk, before receiving a measles inoculation at Willard Elementary in June 1977.

- TIMES-TRIBUNE ARCHIVES Mildred Winger, school nurse, prepares to give a student at Willard Elementary a measles inoculation in June 1977.

- TIMES-TRIBUNE ARCHIVES Helen Fawcett swabs the shoulder of one of the children receiving a measles inoculation at Willard Elementary in June 1977.

- TIMES-TRIBUNE ARCHIVES Principals conducting the measles inoculation program at Willard Elementary in June 1977, from left: Mildred Winger; Dr. Josephine Favin; John Farrell, state department of health; and Eleanor Walsh, supervisor of nurses in Scranton schools.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, The Scranton Times wrote nearly identical articles just about every February — measles had returned to the region.

One, published Feb. 4, 1935, reported “an epidemic of measles is raging in the city at the present time and has taken scores of school children from their classrooms.”

Although it reached every school in Scranton, causing a daily increase of cases, Dr. Arthur E. Davis, the city’s director of public health, said the disease “appears to be of a very mild type” and cautioned residents against panic. By the end of the month, the number of measles cases had risen to 415, although experts said the actual number may have been double that.

The highly contagious disease causes fever, cough, runny nose and a rash. It can cause pneumonia and swelling of the brain and is especially fatal to children.

But by the mid-1960s, public health officials believed measles was on the run, thanks to a vaccine developed in 1963.

A Scranton Times article published June 28, 1969, reported that 25 million children had received the measles vaccine since 1964. In 1968, the Lackawanna County Medical Society began a “measles survey to determine whether a mass immunization program may be warranted.”

As schools began requiring immunizations and doctors began educating patients on the benefits of immunization, measles cases dwindled.

ERIN L. NISSLEY is an assistant metro editor at The Times-Tribune. She has lived in the area for more than a decade.

Contact the writer: (localhistory@timesshamrock.com

Brian Fulton has been the librarian at The Times-Tribune for the past 15 years. On his blog, Historically Hip, he writes about the great concerts, plays/musicals and celebrity happenings that have taken place throughout NEPA. He is also the co-host of the local history podcast, Historically Hip. He competed and was crowned grand champion on an episode of NPR quiz show “Ask Me Another.” Contact: bfulton@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9140; or @TTPagesPast