Hank Aaron, one of the greats of baseball, died today at the 86. His death was announced by the Atlanta Braves.

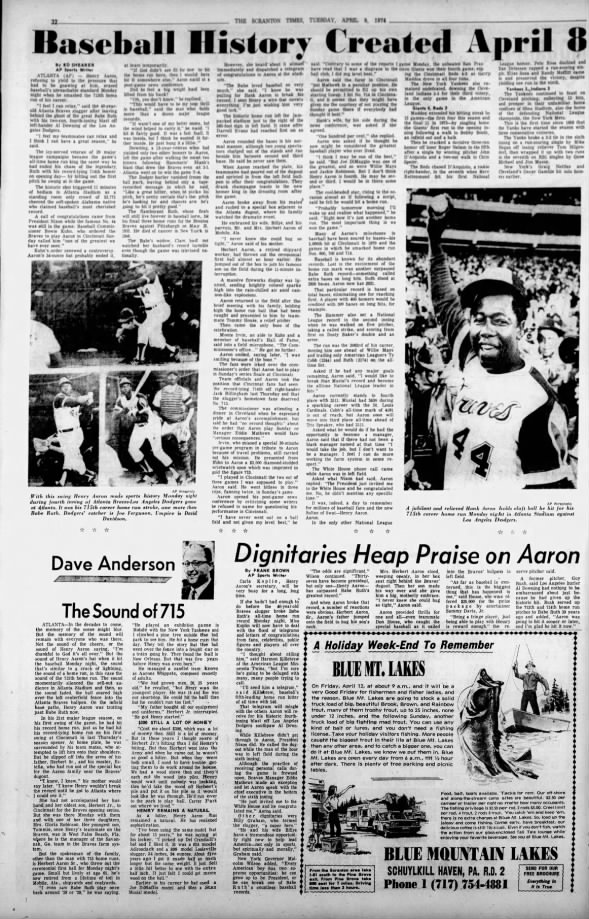

Here are few items from our archives of when Aaron tied and surpassed Babe Ruth’s homerun record and two regional appearances after he had retired from major league baseball.

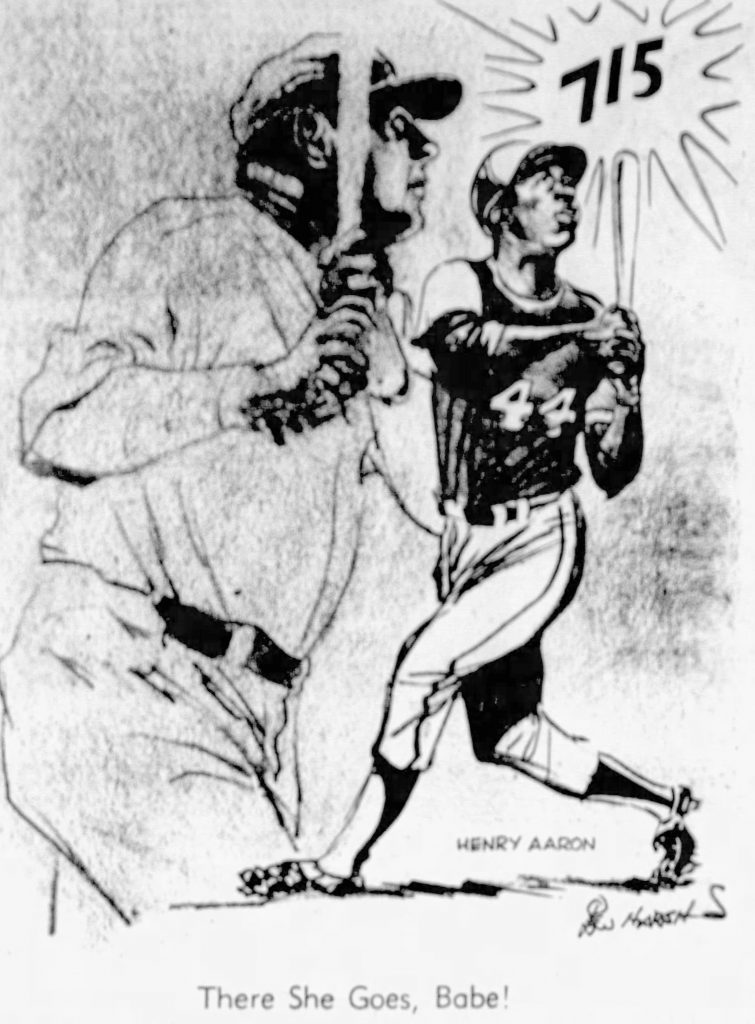

Times’ Cartoonist Lew Harsh marked the moment when Hank Aaron surpassed Babe Ruth’s homerun record on April 8, 1974. The cartoon ran in the Times on April 9, 1974. TIMES-TRIBUNE ARCHIVES

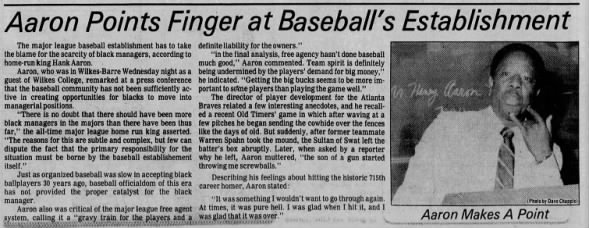

On Nov. 5, 1980, Aaron spoke at Wilkes College (now Wilkes University) as part of the school’s Concert and Lecture series. He talked about major league baseball and its relationship with black players.

Here is an article about his visit from the Nov. 6, 1980 edition of the Citizens’ Voice –

On April 24, 1998, Aaron was the final speaker in Bloomsburg University’s Provost’s Lecture Series. He spoke about his time in baseball and about the prejudices and injustices that black people endure.

Below is a column written by Times’ sports writer Randy Yanoshak about Aaron’s lecture at the university.

Aaron Hammers Away

By Randy Yanoshack, Scranton Times, April 25, 1998

Baseball’s home run king fights prejudice with the same intensity he brought to the baseball field.

BLOOMSBURG – Hank Aaron couldn’t wait to pick up the newspaper Sept. 24, 1957, eager to see a picture of his Milwaukee Braves teammates carrying him off the field after his 11th-inning home run sent them into the World Series.

Looking to relive the overwhelming feelings he enjoyed the night before, Aaron instead was overwhelmed himself, silenced, by the photo he saw alongside his: A black teen-age girl trying to walk up the stairs of Little Rock (Ark.) Central High while a throng of whites surrounded her, trying to keep her from integrating the previously segregated school.

It made me sick, Aaron said Friday. The same day Aaron, a black man, was able to enjoy the adulation of an adoring mostly white public, the prejudice of a nation reared its most ugly head, reminding him just how racially divided the United States was.

Aaron, 64, still hammers today, but now his bat is his mind, his motivation is his conscience, the balls he swings at prejudice, inequality and injustice. Forty-four years since he broke into Major League Baseball with the Braves and 24 since he broke Babe Ruths career home run record, Aaron remains in the national spotlight.

Aarons prodigious ability made him an American icon, both adored and reviled, depending on racial preference. He used that position as a social soapbox from which to attack the injustices blacks had to endure.

Aaron brought his Chasing a Dream speech to Bloomsburg University as the final speaker in the schools 1997-98 Provosts Lecture Series, encouraging the people in attendance to persevere and achieve whatever goals they might have set.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Aarons life serves as a model for chasing dreams. Born in 1934 in a poor neighborhood in Mobile, Ala., Aaron developed his ability swinging a broomstick handle at soda bottle caps and eventually signed in 1952 with the Indianapolis Clowns, a traveling black team.

Three months later, Aaron signed with the Boston Braves, and after Bobby Thomson broke his ankle during spring training in 1954 Aaron found himself the Braves left fielder.

That same year, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the historic Brown v. Board of Education case, striking down the separate but equal doctrine and paving the way for racial integration of public schools.

By the time the Braves beat

the New York Yankees to win the 1957 World Series, Rosa Parks had become the Mother of the Civil Rights Movement, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to quell the disorder surrounding the integration of the Little Rock schools.

And so Aaron found himself the center of attention on the baseball field but helpless to do much off of it. He was invited to Mobile City Hall to narrate the film of the Braves World Series victory but wasn’t even allowed to bring his father. While driving to Florida for spring training the following year, he was forced off the road by a truck full of whites spouting racial epithets.

THE CHASE

Nearly two decades later, as Aaron was closing upon Ruth’s 714 major league home runs, the racist monster reared its head again. His daughter couldn’t leave her college campus. His sons had to be put in a private school. Aaron had to register in several hotels on the road. All of this because of the constant death threats that found their way through the mail.

On the doorstep of breaking what was thought to be an unassailable record, Aaron prayed for the day The Chase would be over I didn’t have the kind of good feeling about the whole thing like I should have, he said. On April 8, 1974, the sixth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.s assassination, Aaron finally hit No. 715.

When I started playing baseball, Jackie Robinson had just broken the color line, Aaron said. People were sitting on their ideas of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, and they weren’t about to let someone come along. So along came a black player, and here I am challenging the most prestigious record in all of sport.

Now Aaron is a senior vice president with the Atlanta Braves, a vice president with CNN, a member of the boards of directors of Stone Mountain Park, Atlanta Technical Institute and Mutual Federal Savings Bank. He is the co-founder of the Hank Aaron Chasing the Dream Foundation, which provides scholarships for young students.

On the field and off, former President Jimmy Carter said, Hank Aaron represented America at its very best.

Aaron’s 755 home runs stand as about the most untouchable record there is a player would have to hit 40 home runs a year for 19 seasons and still Aaron chases a dream of his own.

He fought before to help integrate baseball and in so doing helped open racist eyes all across America. Now he’s helping others chase their dreams. His six lessons:

- To be the best, be who you really are.

- Give your best because the other guy will.

- Overcome doubt.

- Build success from failure.

- The real game is played beyond the ballfield.

- Inclusion make us stronger; exclusion makes us weaker.

Brian Fulton has been the librarian at The Times-Tribune for the past 15 years. On his blog, Historically Hip, he writes about the great concerts, plays/musicals and celebrity happenings that have taken place throughout NEPA. He is also the co-host of the local history podcast, Historically Hip. He competed and was crowned grand champion on an episode of NPR quiz show “Ask Me Another.” Contact: bfulton@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9140; or @TTPagesPast