This story was orginially published in the Times-Tribune on Nov. 18, 2015.

Everhart break-in still a mystery

Publication date: 11/18/2015 Page: 01

Byline: DAVID SINGLETON

City police received notification of a possible burglary at the Everhart Museum at 2:32 a.m. A city patrolman rolled up to the building two minutes later.

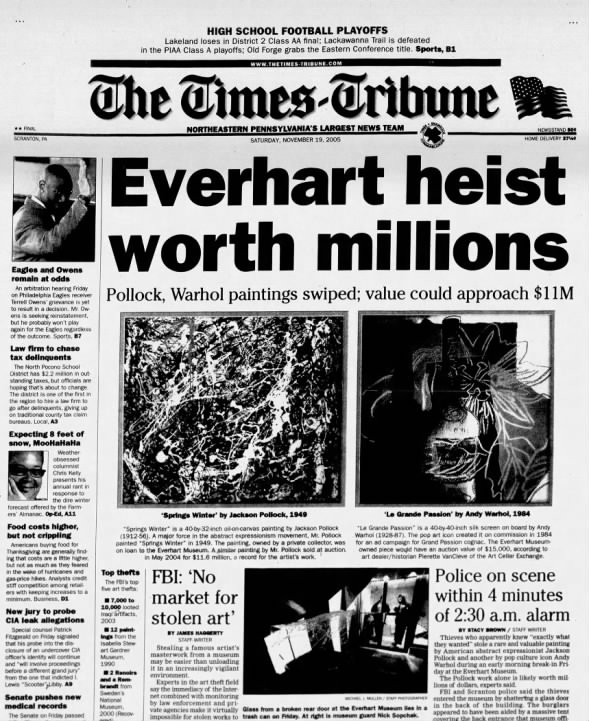

By then, the intruders were gone. Gone, too, were the two pieces of art that police immediately concluded had been the pre-selected targets: a 1949 painting, “Winter in Springs,” by abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, and a 1984 silkscreen print, “Le Grande Passion,” by pop culture icon Andy Warhol.

The day was Nov. 18, 2005.

On today’s 10th anniversary of the theft that stunned the museum and reverberated through the international art world, the crime is unsolved, the artwork unrecovered and many questions surrounding the break-in still unanswered.

Aside from the raw whodunit itself, the most intriguing mystery swirls around the enigmatic “Winter in Springs” and can be summed up in three words: real or fake? Depending on the answer, a heist that was unquestionably worth tens of thousands of dollars could potentially be worth tens of millions.

Ed McMullen, the Everhart curator when “Winter in Springs” owner Arthur Byron Phillips loaned the painting to the museum, finds the theft no less puzzling now than it was when Mr. Phillips quizzed him afterward about his take on the break-in. He told Mr. Phillips what he also would tell the FBI.

“It was speculation, but I thought it was either just some kids, a smash and grab, and his painting is still under some kid’s bed up in Dunmore perhaps, or it was a planned, professional operation, and it’s hanging in some wealthy art collector’s basement,” Mr. McMullen said.

“I mean, what else are you going to think about it?”

Shattered glass

The days leading up to that Friday in November had been busy ones for the Everhart.

The museum’s annual fundraising gala — the Everhart Ball — was scheduled the following night, with hundreds of patrons expected.

“Winter in Springs” and “Le Grande Passion” occupied spaces on separate walls in the second-floor exhibition hall, just two among the several pieces of art displayed there. An exhibit of Pennsylvania impressionist paintings on loan from a museum in Bucks County filled a nearby gallery.

Behind the Everhart, large tents were set up outside the double glass doors at the museum’s back entrance in preparation for Saturday’s festivities.

Investigators later said the tents provided cover as the thieves broke through the back doors and entered the building. Once inside, they tripped the museum’s security system.

Everhart officials acknowledged several days after the break-in that museum employees got the initial notification of the alarm. City police were called after that.

Scranton Detective Todd Spinosi, who was part of the early investigation before the FBI took over, said officers entered the tent at the back entrance and noticed a ladder — apparently used during the tent setup — through one of the doors. Their first thought was it had accidentally fallen and shattered the glass.

“Then they go in through that first door, which is smashed out, and there is a second, interior door,” Detective Spinosi said. “That’s smashed out, too, and there is another ladder.”

He said museum officials checked the building and confirmed only two items missing: the Pollock and the Warhol. Nothing else was disturbed.

Within hours, city police confirmed something else. The museum’s security cameras were not operational — not that it would have made a difference. Museum officials said the camera system was not configured to record.

Authenticity questioned

Experts pegged the value of the Everhart-owned “Le Grande Passion” at about $15,000. The 40-inch by 40-inch silkscreen had been donated to the museum and had a documented provenance.

“Winter in Springs,” a 40- by 32-inch oil-on-canvas, had a more complicated and ultimately more problematic history that called its authenticity into question.

The Everhart received the painting in 2002 from Mr. Phillips, a successful Scranton-born artist whose work the museum exhibited early in his career. Mr. Phillips, who died in 2008, loaned “Winter in Springs” to the Everhart on an anonymous basis, and he was not publicly identified as the owner until three months after the break-in.

Even during the decades prior when the painting hung in obscurity in the Hill Section home of Mr. Phillips’ mother, people who knew him said he consistently maintained he obtained the work directly from Mr. Pollock.

The artist said he first met Mr. Pollock at age 14 during a visit to East Hampton, New York, where the famed expressionist lived and worked and where Mr. Phillips would later have a home.

Mr. Pollock offered to sell him “Winter in Springs” in 1951 or 1952. Mr. Phillips said his mother actually purchased the painting, paying between $800 and $900 after haggling with Mr. Pollock over the price.

Mr. Phillips never had the painting appraised, and he never insured it. He told The Times-Tribune in a 2006 interview the cost of insuring the work would have been prohibitive. He also worried that revealing he had the Pollock or any of several other valuable paintings in his personal collection would make him a target for thieves.

Helen A. Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in East Hampton, said the issue — both at the time of the theft and now 10 years later — is “Winter in Springs” does not appear in Mr. Pollock’s catalogue raisonne. The comprehensive inventory of the artist’s work was first compiled in 1970s and then updated in the 1990s.

Ms. Harrison, who knew Mr. Phillips, said he told her the same story he told others about how he came into possession of the painting. The account, while plausible, is also impossible to verify, she said.

“You can’t take someone’s word for it because a lot of people with ulterior motives — and I’m not saying he had one — make up some pretty interesting tales,” she said.

At this point, she said, the only way to determine whether “Winter in Springs” is a real Pollock would be to subject the painting to rigorous authentication process that would include physical examination by experts and scientific analysis.

“There really is no way to say unless it is examined, and since it is kind of missing in action, that is not going to happen,” Ms. Harrison said.

Several experts noted after the break-in that “Winter in Springs,” if genuine, would be comparable to a similar painting by Mr. Pollock that sold at a 2004 auction at Christie’s in New York for $11.6 million. At the time, it was the most ever paid for a Pollock piece.

However, in the decade since, that figure has been eclipsed at least six times, led by the $58.4 million paid for a 1948 painting by Mr. Pollock at Christie’s in 2013. Just last week, another Pollock painting from 1949 sold at Sotheby’s in New York for $22.9 million.

Red flags

The questions about the authenticity of “Winter in Springs” raised red flags as the FBI’s Philadelphia-based National Art Crime Team took the lead in the investigation.

Some investigators suspected Mr. Phillips forged the painting or had someone else forge it and then presented it to the Everhart as a genuine Pollock in an attempt to enhance its cachet, possibly as a prelude to trying to sell the piece.

Mr. Phillips’ inability to authenticate “Winter in Springs” also prompted insurance executive Brian J. Murray, whose company provided coverage for the Everhart collection, to flatly brand the painting a fake.

Murray Insurance eventually paid $100,000 to the Everhart for the loss of “Le Grande Passion” based on an independent appraisal, but no claim was ever paid for “Winter in Springs.” Mr. Murray was sentenced to state prison in 2011 for insurance fraud unrelated to the Everhart theft.

In February 2006, the Everhart issued a statement in support of Mr. Phillips, saying it believed he made a good faith loan of the painting “as an authentic Jackson Pollock despite suggestions to the contrary.”

“Until that time when (the painting) is recovered, all arguments for and against its authenticity are exercises in speculation and are a disservice to both Mr. Phillips and the Everhart,” the statement said.

Mr. McMullen, who left his curator position at the Everhart a few months before the break-in, said the theft and its aftermath took a toll on Mr. Phillips.

“It was a sad, sad thing that Arthur’s integrity and honesty were questioned at that time,” Mr. McMullen said. “It broke his heart.”

Although he was an eccentric, Mr. Phillips was also a respected artist and serious collector who would have been repulsed by the very notion of passing off a forged work of art as genuine, Mr. McMullen said.

“Here you have a remarkable artist in his own right, a very successful man, a multimillionaire, an avid art collector,” he said. “All of those things would point to the fact that (“Winter in Springs”) was authentic. I suppose it couldn’t be, but I’d bet my life that that painting is real.”

Joe Palumbo, who acted as Everhart’s spokesman after the break-in, falls into the same camp. While there is “always that chance” the painting was a fake, he said, he tends to believe it was genuine.

“Arthur did a lot of odd things, but I just don’t think he’d make it up. He really had no reason to,” Mr. Palumbo said. “He was a very, very successful artist — in fact, one of the most successful artists around, and I don’t just mean in Scranton, Pennsylvania. His work is all over. He would do a portrait for somebody, and it might be $100,000. He was at that level.”

Case closed

Both “Winter in Springs” and “Le Grande Passion” are still listed on the FBI’s stolen art database. The agency maintains the database mostly for public awareness, and the Pollock’s inclusion does not mean the FBI takes a position on its authenticity, Special Agent Jake Archer said.

“We don’t have sufficient information either way,” said Mr. Archer, who works out of the FBI Philadelphia office and is one of 14 agents nationwide assigned to the National Art Crime Team.

As for the Everhart case, it is considered closed, although the FBI will still pursue any solid leads it gets, he said.

“We will certainly review any credible information,” Mr. Archer said.

In the decade since the break-in, the Everhart has received no additional information about who might have committed the crime or the fate of the artwork.

“No clue,” Amy Everett, director of development and marketing, said last week.

Stolen artwork turns up occasionally and Mr. McMullen said he would like to see the Pollock in particular recovered and authenticated if only to provide a measure of redemption for Mr. Phillips.

“I’m not sure why — I’m no expert or anything like that,” he said. “But I’m certain they would find it to be real.”

Contact the writer: dsingleton@timesshamrock.com

Brian Fulton has been the librarian at The Times-Tribune for the past 15 years. On his blog, Historically Hip, he writes about the great concerts, plays/musicals and celebrity happenings that have taken place throughout NEPA. He is also the co-host of the local history podcast, Historically Hip. He competed and was crowned grand champion on an episode of NPR quiz show “Ask Me Another.” Contact: bfulton@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9140; or @TTPagesPast