BY PAUL GOLIAS

Ray Clarke’s name will be ever synonymous with the Huber Breaker.

Generations to come will include fathers telling their children, “He’s the guy who came close to saving the breaker.’’

Ray humbly sidesteps the accolades, citing the team effort over 24 years to preserve and protect the historic anthracite processing facility.

“We tried, oh Lord how we tried,’’ Clarke said in an interview that explored his gut-wrenching efforts, from pulling weeds on the walkway to the anthracite miners’ monument to packaging barbecued chickens, sold to pay the electric bill at the park.

Clarke showed his dedication to the cause and the park by pulling weeds (alongside his wife, Jane) but he was a dreamer, too. The dreams were large scale, too.

Of Ray Clarke’s many ideas for a Huber Breaker historic site, the most unique would have been installation of a plexiglass walkway directly over the shaft at the Huber Colliery.

The shaft was more than 200 feet in depth. A cage, lowered and raised by cables, carried miners and equipment to the lower levels of the mine. Miners and laborers would then walk underground to the faces of the workings. Holes would be drilled, dynamite sticks inserted and coal would be blasted. Anthracite was then shoveled into small coal cars.

In the pre-locomotive days, mules pulled loaded cars to either slopes or shafts. The Huber Colliery had both.

Clarke thought it would be wonderful for people to peer down the shaft, lighted to whatever depth the water level would allow.

“Imagine kids having the opportunity to look down a mine shaft,’’ Clarke beamed.

Ray’s glass bridge idea has merit. A 10-foot wide glass bridge called Skywalk extends 70 feet out over the rim of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Visitors can peer through the glass platform 4,000 feet to the floor of the canyon. It is a great view of one of the world’s Seven Natural Wonders.

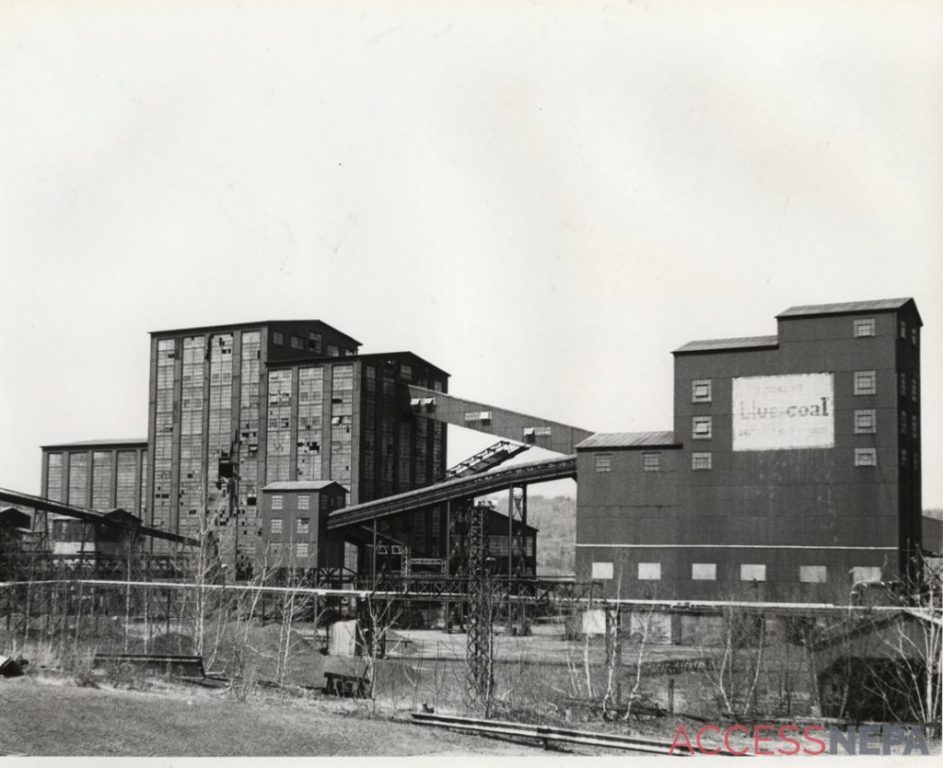

SUBMITTED PHOTO

The Huber Breaker in Ashley was the last remaining coal breaker in the anthracite coal region of Luzerne and Lackawanna counties. It was demolished in 2014.

“I was there,’’ Clarke said, “in my stocking feet!’’ He still sees buses loaded with school kids, coming to the Huber Skywalk to look down into a coal mine.

Ray’s “big picture’’ view, one shared by Huber Breaker Society colleagues over the years, included a preserved breaker, the miners’ park and monument, walking trails, kiosks telling the anthracite mining story, the still-emerging coal and railroad era artifacts, a museum, education center, Steamtown train excursions to Ashley from Scranton, the Ashley Planes heritage park and the Delaware & Lehigh Corridor hiking trail through Ashley.

Even if the cost factor precluded restoring the breaker interior, Clarke said, the breaker itself could have been preserved. A former Iron Workers union member (Local 489), Clarke had lined up iron workers to repair the breaker’s facade, “the roof, the (metal) skin and the windows,’’ he said.

The key problem: The Huber Society could not secure ownership. The society did own 3.1 acres donated by Earth Conservancy which took over some 14,000 acres of Blue Coal Corporation land in 1992, but the breaker and 26 acres of land in Ashley were owned by No. 1 Contracting Co., or Al Roman.

For years, Roman promised he would donate the breaker to the society. Clarke now reveals that Roman, who died in December 2015, wanted to do a land swap with Luzerne County That did not materialize and Roman went bankrupt, eventually losing the breaker and land in a U.S. Bankruptcy Court sale to Paselo Logistics, Philadelphia.

The tragic outcome of that sale, to anthracite historians, was the razing of the breaker in 2014 and sale of its steel for scrap value.

DAVE SCHERBENCO / ACCESS NEPA

The grounds of the Huber Breaker as they appeared in 2009.

The breaker is gone, but the Anthracite Miners’ Memorial Park lives on, albeit now owned by Ashley Borough as the Huber Breaker Preservation Society ponders its future, from its name to its mission.

A lokie that once hauled mine cars at Wanamie and elsewhere has been saved and it sits on a section of track in the park, awaiting a protective pavilion and a coal-laden mine car. Kids will have the opportunity to see something of the mining era, if not a breaker.

Ray Clarke was born Feb. 28, 1934, in Ashley, one of eight children of Patrick and Ellen Nealon Clarke. His father worked at Sugar Notch’s No. 9 colliery until breaking a leg in an accident; thereafter he served as custodian at Ashley High School from which Ray graduated.

Ray helped his brother, Joe, deliver newspapers in the breaker neighborhood. Because Joe had a bicycle, he did South Main Street, leaving Ray to climb steps in miners’ boarding houses, and deliver to stores and barrooms.

Following a two-year stint in the Army, as a paratrooper in the 11th Airborne, Ray married Jane in 1956. They had eight children also, four of whom have passed away.

A trip by Ray and Jane to Ireland in 1979 led to the decision to open the gift shop, and flowers were added to the inventory and became the shop’s centerpiece item. Ray said he had “walked the beams’’ as an iron worker and “heights did not bother me,’’ but he enjoyed the Clarke’s Imported Gifts & Floral years.

The Huber society was formed in 1990. Early leaders included John Jablowski, a councilman and later mayor of Ashley; the late Paul Zavada, an accountant, and George Lehman, who operated the Newtown Cafe with his wife, Nancy.

Clarke said many people deserve credit for launching the society and trying to save the breaker. A feasibility study was done and society members, including college professor Dr. Anthony Mussari, tried vainly to get Roman to donate or even sell the breaker.

DAVE SCHERBENCO / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Ray Clarke stands at the Huber Breaker Memorial site on Tuesday, Oct. 13, 2020.

The late Bob Janosov, a history professor at Luzerne County Community College and a member of the Pennsylvania Historical Commission, helped secure a $90,000 grant toward preserving the breaker, but Roman remained an issue. The funding was lost.

Clarke became chairman of the society board and treasurer in 2006. He stepped down in February 2019, after 13-plus years, he said. George Lehman is chairman pending decisions on the future of the organization.

Clarke gives high marks to state Sen. John Yudichak, state Rep. Eddie Day Pashinski and former state Rep. Kevin Blaum as strong supporters of the breaker cause.

“I was the only guy with free time. No one else wanted it,’’ Clarke said of the chairmanship. But, he persevered, with the aid of new board members and volunteers, including Steve Biernacki, Pat Kennedy, Bill Landmesser, Don Kane and Leo Czereck. Bill Best served as society president for most of Clarke’s tenure. Best arranged many mining and railroad-related speakers to spark public interest in the society’s work.

But Ray Clarke will be remembered as the guy who sat outside the bank selling T-shirts and chicken dinner tickets, striving to keep the preservation society afloat as many hoped the dreams would one day become reality.