“You’re an idiot.”

That’s what you’re thinking. I know it. I think that, too. Field of Dreams is rather universally beloved among most sports fans, young and old. It holds a special place in the American sports psyche. It’s the quintessential love letter to baseball, and many screenwriters and actors have tried to make that movie in the past and will again in the future without so much as brushing past the success. I’ve covered a handful of Penn State games at Kinnick Stadium in Iowa, and a few times, I’ve taken the nearly two-hour drive from Cedar Rapids to Dyersville — in a time crunch, in bad weather, for reasons I can’t fathom — just to spend 20 minutes at an empty baseball diamond in the middle of a cornfield. Is this Iowa? No, it’s Heaven.

That’s what you’re thinking. I know it. I think that, too. Field of Dreams is rather universally beloved among most sports fans, young and old. It holds a special place in the American sports psyche. It’s the quintessential love letter to baseball, and many screenwriters and actors have tried to make that movie in the past and will again in the future without so much as brushing past the success. I’ve covered a handful of Penn State games at Kinnick Stadium in Iowa, and a few times, I’ve taken the nearly two-hour drive from Cedar Rapids to Dyersville — in a time crunch, in bad weather, for reasons I can’t fathom — just to spend 20 minutes at an empty baseball diamond in the middle of a cornfield. Is this Iowa? No, it’s Heaven.

There’s just something about Field of Dreams that gets into you and stays with you.

And yet, as I write those words, I wonder if I am underrating where it belongs on this list. I think you can argue it as a top 5 bad, disappointing, frustrating sports movie. I just…I couldn’t live with myself if I did. After all, as part of our 10 best sports movies list that published recently, our resident movie critic Joe Barres ranked it No. 1. I actually ranked Field of Dreams at No. 10 on my own personal “best” list.

Yes, this is a great movie and a bad one. It’s possible to be both, and Field of Dreams proves that better than most.

For the first half of my life, Field of Dreams would have ranked as my favorite sports movie, and that’s my fault. I got caught up in the storyline. In “The Voice.” In Kevin Costner’s character, Ray Kinsella, blindly and faithfully following a passion. In Terrence Mann’s stirring speech, the words of which resonated so much with me, I memorized them as a kid. (My hidden talents, to this day, remain being able to recite the “People will come…” speech and all the lyrics of “Ice, Ice Baby.”) In the look on Costner’s face in that mesmerizing closing scene, when he realizes the voices weren’t leading him to Shoeless Joe Jackson and the 1919 Black Sox, but to his father, there in the flesh on a sparkling summer night when a game of catch between a father and a son made the world perfect. That scene brought me to tears back then, as a pre-teen. And it does today as a middle-aged father.

Unlike that scene though, this movie was far from perfect. I could ignore that, if the imperfections didn’t come as the result of laziness.

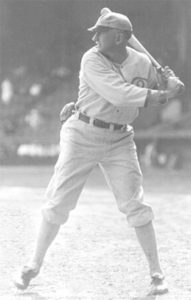

Proof that legendary slugger Shoeless Joe Jackson hit left-handed during his career that ran from 1908-20. In the movie, he was portrayed as a right-handed hitter and lefty thrower by Ray Liotta. In reality, he batted left and threw right.

When I was a teenager, I had a pretty good idea of what Shoeless Joe Jackson was all about because of this movie. And then, I realized I was led astray. Jackson was one of the best left-handed hitters in the early part of the 1900s — Costner even had a line in the movie in which he, correctly, told his on-screen daughter, Karin, that Babe Ruth copied his swing. But in the movie, Jackson was played by Ray Liotta, who batted…right-handed?

A couple of camera tricks and some editing magic — it’s the movies, after all — could have portrayed Liotta hitting left-handed and given a far more historically accurate look at one of the main characters in the film and one of the most intriguing in the game’s history.

I have talked to some fans of the movie who have shrugged that off as an oversight, but here’s what I keep coming back to: If I don’t believe that’s Shoeless Joe wandering aimlessly out on that “lawn” in the middle of the cornfield — and since he’s hitting right-handed, I don’t — The Voice loses credibility. And I have to believe The Voice, that if he builds it, they will come, that there is a pain that needs to be eased. I have to believe, as a viewer, those are not just the 1919 Chicago White Sox, but that they’re ghosts.

I know this movie was made about seven decades after the 1919 scandal, but almost everything about the Black Sox in the movie seems wrong, with just a little bit of research on that team. There’s a scene where first baseman Chick Gandil and pitcher Eddie Cicotte get into a bit of an argument during a practice that completely blows the credibility of that group of guys being the White Sox. Jackson tracks down a fly ball on a dead sprint, the first baseman Gandil calls him a show off, and the pitcher Cicotte tells him to “stick it in his ear.”

“If you’d have run like that against Detroit, I’d have won 20 games that year,” Cicotte yelled.

“For Pete’s sake, Cicotte, that was 68 years ago. Give it up,” Gandil shot back.

Great lines. Because of that, I’ll overlook the fact that Cicotte won 20 or more just twice in his career, and that the only time he didn’t win 20 and got even close to doing so — he won 18 in 1913 — Gandil wasn’t on his team. So there’s no way a momentary lack of hustle on Gandil’s part ever cost Eddie Cicotte a 20-win season.

But, that’s the sort of thing I expect to nit-pick in a movie.

What I don’t expect is teammates who have been forever linked to mispronounced each other’s names. The correct pronunciations of both their names aren’t easy to decipher with a quick read — Gandil (GAN-dul) and Cicotte (SEE-kot) — but they do have a prominent place in baseball history. A phone call to practically any baseball historian would have confirmed proper pronunciations, but in that give-and-take, Gandil pronounced Cicotte incorrectly (suh-CO-tee) and Cicotte pronounced Gandil incorrectly (gan-DILL).

A young Archie Graham, played by Frank Whaley, immediately recognized three players he could not possibly have known existed as he entered the Field of Dreams.

I love the Moonlight Graham character. Burt Lancaster is incredible in one of the final roles of his incredible career. The scene where the young Archie Graham races off the field to help dislodge the chunk of hot dog from a choking Karin’s throat, fully understanding and OK with the fact that he’d never get to play again, remains powerful decades after it was filmed. But the real Moonlight Graham was born in 1877. The one big-league game he played in was on June 29, 1905. But when Ray and Terrence brought him to that field in Iowa for the first time as a youngster, the three players he immediately recognized were “Smoky” Joe Wood, Mel Ott and Gil Hodges.

Ott was born four years after Graham made his debut; Hodges, nearly two decades later. Wood didn’t make his major league debut until 1908. There’s just no way a young Archie Graham — who incidentally, was a lefty hitter in real life and a righty in the movie — would have known who any of those players were.

Again, you have to think they’re ghosts. A baseball historian probably doesn’t see them as such, and I’m not certain how you can overlook every unnecessary pratfall in the writing and still consider this film on the level of Rocky or A League of Their Own or Bull Durham or For Love Of The Game.

I do — more accurately, I try — because I want to. The story is that good. The work of the main characters, especially Costner and James Earl Jones, are that good. The message and the sentiment and the soul of that movie has never been matched by another baseball movie. But the small details that aren’t so small, it’s amazing to think about how many of them production got wrong. Pretty much all of them, really, to the point where it’s worth wondering if it was intentional.

I rank this on the best and worst lists, because it’s both. It’s both perfect and an absolute wreck. It’s inspired, and it’s terrifically lazy. I love it, and I hate it.

Donnie Collins has been a member of The Times-Tribune sports staff for nearly 20 years and has been the Penn State football beat writer for Times-Shamrock Newspapers since 2004. The Penn State Football Blog covers Nittany Lions, Big Ten and big-time college football news from Beaver Stadium to the practice field, the bowl game to National Letter of Intent Signing Day. Contact: dcollins@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5368; @DonnieCollinsTT