BY THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

(EDITOR’S NOTE: “Apollo 11: An AP Special Anniversary Edition,” available in paperback and e-book exclusively on Amazon.com , chronicles America’s journey to the moon. The following is an excerpt from Chapter 12.)

Footprints on the Moon

There was always the moon, and with it, unwritten history. Perhaps the story of Creation itself.

Always the moon, staring out of everyone’s sky. Nothing has so captured the eye and mind of man. She stands, as always, large on the horizon, shrinks in her zenith. On hot muggy nights, she flames as orange as the sun rising from the ocean. On blue summer days, her ghostly crescent haunts the daytime sky. She is a pristine silver ball in the clear desert night, small and alone. She conspires with the sun to order the tides of earth’s oceans. Yet the simple cycle of her passage keeps time with the metabolism of mice and fiddler crabs. The sun gives man day and night. The moon gives him weeks and months. So many things tick to the lunar clock. What makes the grunion run? What times the rise of human fertility? What brings the rock crab ashore to feed? What alone eclipses the sun? The moon. The moon. The moon.

July, 1969. The moon was no longer a total mystery. As Neil Armstrong said, Apollo 11 would not be a flight into the unknown. The moon had been measured, compared and poked at. She was more a small planet than a moon, the largest of 32 moons that shadow the nine planets of the solar system. She measured 2,160 miles in diameter, 6,790 miles around the waist. She was less dense than earth. Even though she was one-fourth the size of earth, she had only 1/100th the mass. Her gravity was one-sixth as strong as earth gravity. A 150-pound earthling would weigh only 25 pounds on the moon. She was a lady of extremes. Her day was 14 earth-days long. Under the beam of sun1 and the emptiness of shadow, her temperatures ranged from 243 degrees above to 279 degrees below zero.

For all the small physical facts, there were larger questions that persisted. How did it all begin? There were three prime theories: that the moon erupted out of the earth, thrown off by centrifugal force when the earth was spinning faster; that both bodies formed at the same time, condensing out of the primordial gases of creation; that the moon was a wandering planet captured by earth’s gravity. Daughter? Sister? Captive wife?

Those questions remained unanswered as Apollo 11 readied for flight. They were part of the reason for going.

Thus in July, 1969, as always, the moon, strange foreign body in earth’s sky. Against the new image of her bleak craters and mountain ranges the world considered three men?_?Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins.

On the eve of history, perhaps men do not sleep well, or perhaps they are not meant to. Before they slept Saturday night, their rest period was delayed an hour-and-a-half because of a pesky communications problem, finally tracked down. They were awakened at 7:02 a.m. Sunday, Armstrong with five-and-a-half hours sleep, Collins with six, Aldrin with five. It was the shortest rest period of the flight. They spent half an hour on breakfast. Mission Control beamed up the latest on their families, and the morning news. Aldrin was told his son had a visit to the space center with an uncle.

Then it was time to get down to business. Aldrin was the first into the Eagle at 9:20 a.m. Almost an hour later, Armstrong slipped through the tunnel to join him. From then on, they were Eagle. Collins was Columbia. At 12: 32 p.m., they pushed a button that extended the landing legs of Eagle.

Thus did Columbia and Eagle, still linked together, arrive at this incredible time and place, out of sight and out of radio contact with earth on their 13th orbit of the moon. Some 100 hours had passed since they had left their home planet. Now they were 240,000 miles away from it, about to commit themselves to history. Behind the moon, Collins pressed a simple button. Latches clicked open. Springs gave Eagle a gentle shove. On earth they waited for word. Finally the radio signal came through. It was Armstrong’s voice crackling with static. “The Eagle has wings,” he said.

Now briefly they flew formation together, Collins looking over the weird little ship Columbia had borne this far. “Looks like you’ve got a mighty good looking flying machine there, Eagle,” he said, “despite the fact you’re upside down.” ”Somebody’s upside down,” replied Eagle. Less than half an hour later, Collins gave Columbia a spurt of rocket power and dashed some two miles ahead, allowing Eagle flying room. “See you later,” he said. Eagle was on its own.

Again, they passed behind the moon, to that point in orbit where major changes are made, again out of sight of earth and out of radio contact. Armstrong and Aldrin tilted their little ship so that the rocket faced the direction of flight. When they emerged from behind the lunar shadow, the earth heard Armstrong say, “The burn was on time.” Collins confirmed, “Listen babe, everything is going just swimmingly.” The descent to the moon’s surface had begun.

Eagle flew the long, looping arc, riding its tail of rocket fire like a brake, cutting into its 3,700 miles per hour speed.

“Current altitude about 46,000 feet,” reported Mission Control. “Everything’s looking good here.”

Eagle: “Our position check downrange shows us to be a little off.”

Mission Control: “You are to continue powered descent. It’s looking good. Everything is looking good here.”

There was total silence in Mission Control, except for the reassuring voice of the cap com, the business-like reports over the engineering and flight dynamics channels. “Two minutes 20 seconds, and everything looking good,” reported Mission Control. “I’m getting a little fluctuation,” said Eagle. “Looking good,” said Mission Control. “Shows us to be a little long,” persisted Eagle. “You are go to continue powered descent,” insisted Mission Control. “You’re looking good.”

“Got the earth right out our front window,” reported Eagle. The guidance computer on board was showing some variations. “You’re looking great, Eagle, you’re looking great,” Mission control reassured. “You’re go for landing.”

“Roger, understand,” said Eagle. “Go for landing, 3,000 feet . . . 2,000 feet . . . Okay, it looks like it’s holding.”

Armstrong’s voice was clear, and as brisk as a stock market report. But his heart rate was running some 40 beats a minute higher than normal. Now some thing happened to send it to 156 beats a minute, but his voice never betrayed it. He saw the landing site below strewn with boulders. He overrode the automatic landing stem. grasping the rocket controls in his right hand, skimming over the littered field, searching out a clear spot: “540 feet . . . 400 feet, coming down nicely . . . 200 feet . . . 100 feet . . . 75 feet, still looking good, drifting to the right a little . . .”

At 40 feet billows of dust kicked up by the rocket rose around the craft. “Okay . . . engines stopped.”

“Houston,” said Armstrong tentatively. A long pause. Then: “Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

“Roger, Tranquillity,” sighed Mission Control. “We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again.”

The time was 4:18p.m. Cape Kennedy time, Sunday, July 20, 1969. Man had landed on the moon.

In Mission Control, nearly 100 space agency experts jammed the viewing room, literally looking over the shoulders of the flight controllers sitting behind their console on the floor below. Among them were John Glenn, Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan from Apollo 10, Jim McDivitt and Walt Cunningham from Apollo 7. “It’s probably a good thing Armstrong doesn’t know what’s going on here on earth,” said Cunningham. “Neil’s the calmest guy on the communications loop.” It wasn’t a time to be calm. All of the flights, all of the men had led to this moment. Flight director Eugene Kranz slapped his console in delight. Behind him everyone was cheering, applauding. Kranz suddenly realized that discipline had broken down. “All right everyone,” he called out. “Get settled down.” The day wasn’t over yet. There were grander moments in store.

In the White House, President Nixon watched televised reports with Frank Borman. The last 22 seconds, he said, was more like half an hour. When he caught his breath he sent the astronauts his congratulations. “It was,” he said, “one of the greatest moments of our time.”

The last minute difficulties were explained by Buzz Aldrin: “That may have seemed like a very long final phase. The auto targeting was taking us right into a football-field sized crater. There’s a large number of big boulders and rocks for about one or two crater diameters around it. And it required us to . . . fly in manually over the rock field to find a reasonably good area.”

Armstrong noted: “You might be interested to know that I don’t think we noticed any difficulty at all in adapting to one-sixth gravity. It seems immediately natural to move in this environment.”

Ahead, he said, was “a relatively level plain, cratered with a fairly large number of craters of the five-to-50-foot variety, and some ridges, small, 20-30 feet high. I would guess. And literally thousands of little one- and two-foot craters around the area. We see some angular rocks several hundred feet in front of us that are probably two feet in size and have angular edges. There is a hill in view just about on the ground track ahead of us. Difficult to estimate, but might be a half a mile or a mile.” ”Be advised,” said Mission Control, “there are lots of smiling faces here, and all around the world.”

“There are two up here also,” replied Armstrong.

“Don’t forget the one up here,” called down Collins on his lonely patrol. Then he added his compliments: “Tranquillity Base, you guys did a fantastic job.”

“Just keep that orbiting base up there for us,” Armstrong replied.

The first duties were to check out the spacecraft. That done, Armstrong and Aldrin concentrated on describing sights no one had ever seen before. “Out of the hatch,” Aldrin said, ‘Tm looking at the earth, big and round and beautiful.” The sun played games with the color of the lunar rocks around them. “Almost every variety of rock you could find,” Aldrin said, looking out the window. “The color varies, depending on how you’re looking at it. Doesn’t appear to be much of a general color at all.”

Eagle stood some four miles beyond its planned landing site. It was also on a slight tilt, but not enough to endanger takeoff. “The guys that said we wouldn’t be able to tell precisely where we are are the winners today,” Armstrong said. “We were a little busy worrying about program alarms and things like that in the part of the descent where we would normally be picking out our landing spot.”

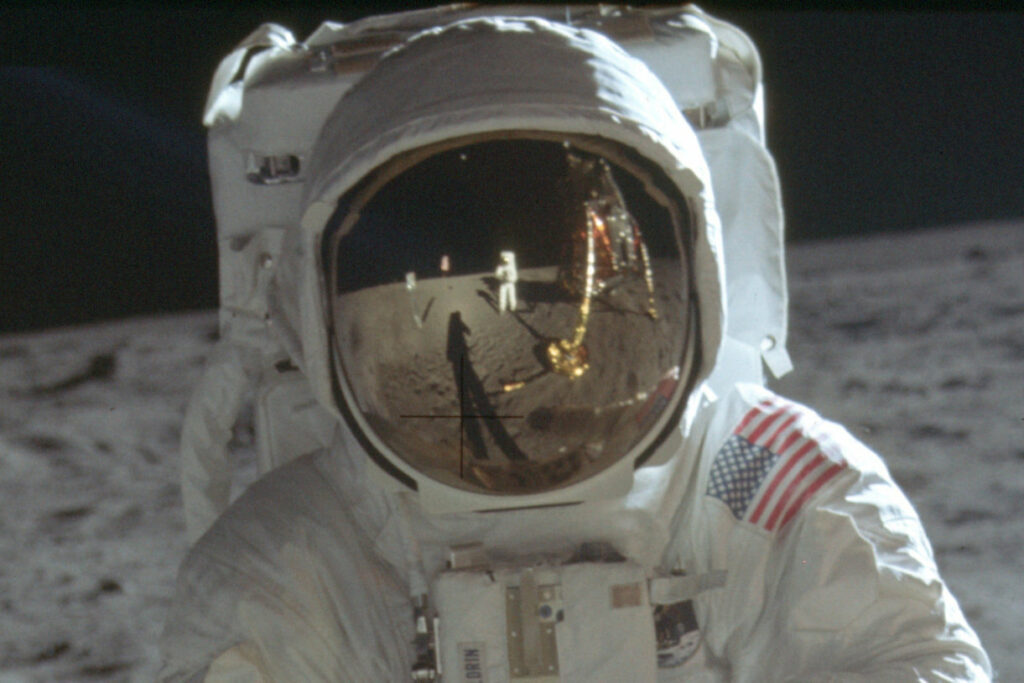

Slowly, they bled the pressure from their spacecraft, letting oxygen out, vacuum in. At 10:40 p.m., Armstrong reported, “The hatch is coming open.” Then, following Aldrin’s instructions, he began to back out onto the porch of the spacecraft, taking care that his suit did not catch or snag in the narrow opening. It was slow going. His 185-pound suit, weighing only some 30 pounds in lunar gravity, was more a hindrance because of its bulk than its weight. Suddenly he was standing on the porch of Eagle, beginning the tentative steps down the nine rungs of the ladder. On the way he pulled a lanyard releasing an equipment shelf and a television camera. Now, on screens all over the earth, you could see the stark shadows, and there, swinging, searching, a boot, Armstrong’s boot. Bit by bit, the whole man appeared. Now, off the last rung, onto the saucer-like footpad. Then, cautiously again, unsure of what was below it, he stepped with his left foot, a size 9½ foot in a clumsy, awkward step. He pressed the lunar surface at 10:56 p.m. His first words were, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” For 20 minutes he walked alone on the alien soil of the moon before Buzz Aldrin followed the same backward route down the ladder to join him. Aldrin looked around and his first words were, “Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. A magnificent desolation.”

Armstrong walked cautiously at first, almost in a shuffle, then with growing confidence. He found the footpads of Eagle had pushed only an inch or two into the lunar soil after a four-foot drop. His own foot, he guessed, pressed in only a fraction of an inch. But he could see his footprints in the dusty surface.

At 11:42 p.m. Armstrong and Aldrin unfurled the Stars and Stripes and erected the rod that ran along the top to keep the flag taut in the airless, windless atmosphere of the moon. Aldrin stood back and saluted. Armstrong stood at attention. Only minutes before, the spacecraft commander from Ohio stood at the side of Eagle reading the plaque affixed there in a steady voice to a listening world. “Here man first set foot on the moon, July, 1969,” Armstrong read. “We came in peace for all mankind.”

From the Oval Room at the White House came President Nixon’s voice beamed by telephone and radio across 240,000 empty miles. “I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of what you have done for every American,” he said. “This has to be the proudest day of our lives. For people all over the world, I am sure that they too join with Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is. Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man’s world. As you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquillity it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to earth. For one priceless moment in the whole history of man all of the people on this earth are truly one. One in their pride in w at you have done, one in our prayers that you will return safely to earth.”

Said Neil Armstrong, “It is a great honor and privilege for us to be here representing not only the United States but men of peaceable nations with an interest and a curiosity and a vision for the future.”

In the daring minutes that followed, Aldrin loped across the lunar panorama before the eye of the television camera set up now to survey the Eagle and the men of the Eagle. Both men collected soil and rock samples, set up a metal foil shade to catch the subatomic particles blown through space by the sun’s solar wind. They also set up a seismometer to measure tremors in the lunar crust, and a mirror-like device to reflect laser light back to earth and help measure the distance to the moon to an accuracy of six inches.

They packed up everything that had to go in big white suitcase like boxes, the rock, the core samples, the bags of dirt, the foil that faced the solar wind. The seismometer, the mirror, the flag remained behind. At 1:11 a.m., Monday, July 21, 1969, they closed the hatch of Eagle behind them.

Within six hours, Armstrong and Aldrin were sitting with Collins again in the relative comfort of Columbia. There had been a little trouble docking, but nothing serious. The astronauts actually made the transfer to the mother ship some two hours early. Eagle was cast away, to remain in space as long as its orbit of the moon would last. Eventually it too would crash to the lunar surface. Just 11 hours after they left the moon, they fired Columbia’s engine for two-and-a-half minutes and drew a bead on the planet earth. Armstrong and Aldrin were tired, and Mission Control ordered up some sleep.

The trip back to earth was quiet and restful, if not quick. With hardly a problem, Columbia flashed through earth’s sky and splashed down in warm Polynesian waters of the Pacific at 12:50 p.m. Thursday, July 24, eight days, three hours and 18 minutes after it took wing at Cape Kennedy, Fla. It landed just nine miles from the aircraft carrier Hornet and the eyes of President Nixon, on hand to greet the astronauts even if he could not shake their hands. They immediately went into the elaborate quarantine system in which they would remain until August 11, to protect the earth from any possible contamination from germs on the moon. The President faced the three men through a glass window in an isolation van, flanked by a Marine honor guard. All stood at attention as the Navy band struck up with “The Star Spangled Banner.” The President then proclaimed, “This is the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation.”

“As a result of what you have done,” he said, “the world has never been closer together.” He invited them to a state dinner in Los Angeles on August 13. “Will you come?” he asked. “We’ll do anything you say, Mr. President,” Neil Armstrong answered. The three faces in the window were fresh and smiling broadly. Collins had grown a moustache on the flight. There was one moment of irony after the astronauts took their only open steps on the carrier, a 10-foot walk to the van from the helicopter that picked them up. Just after the door of the isolation van closed, a scientist in a short-sleeved yellow shirt quickly sprayed the pathway with disinfectant. It had to be the strangest hero’s welcome ever.

Three earthlings were put in isolation during those harried days following Apollo 11’s return. First, a photographic technician touched a pack of moon film and got black moon dust on his hands. Then, two men working with the lunar rocks with their gloved hands inside a small vacuum chamber became contaminated when the gloves cracked open. The astronauts remained healthy, a trifle bored perhaps, but healthy in isolation.

The experiments they left behind and the rocks they brought with them were already beginning to speak of the moon’s history. The seismometer recorded what was either an earthquake or the impact of a meteor somewhere on the moon. And a scientist said that the pieces of moon under study were “like an Aladdin’s lamp. Rub them with the right instruments and they will tell you the secrets of the universe.”

The adventure of space was also an Aladdin’s lamp of sorts. It revealed once more that man’s greatest deeds often arise from his strangest motives. A cold war between nations had given mankind a new planet to walk on.