For nearly 100 years, a member of the Reilly family has ridden the rails in a multitude of jobs aboard trains.

Reillys have served as conductors, union leaders and engineers since the mid- to late-1920s, when patriarch Frank Sr. joined the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western lines as a locomotive engineer, and began what would become a long line of descendents with railroading in their blood.

But on July 5, the storied family legacy came to a close when 61-year-old Mike Reilly, a conductor for New Jersey Transit, waved goodbye to his career and friends gathered as he stepped off an engine in Dover, New Jersey, signaling his retirement after 41 years.

On a recent afternoon in Dunmore, two generations of Reillys gathered to reflect on the traditions and lessons railroading has held for their loved ones, through good times and bad.

“It’s a tough life,” admitted Pat Reilly, 66, a former general chairman of the United Transportation Union, and Mike’s older brother, who retired in 2013 after 42 years.

“You can never plan events with your family. On the railroad, you either had good wives or were divorced,” the Dunmore resident explained.

Job calls often came in the evenings with little notice to get on board, and kept the men of the family away for long stretches of time, frequently at odd hours. Turning down a job could mean losing work for days, and so dedicated providers endeavored to do whatever was necessary to take on the assignments, sometimes to the detriment of their loved ones at home.

But the pay was good, and especially for young men just starting out in life, it offered discipline and great earning potential in exchange for their commitment.

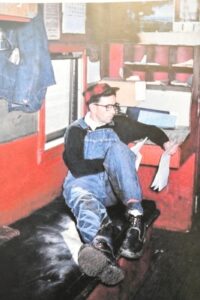

Submitted Photo

Frank Reilly Jr. sits in a caboose.

For the Reillys, the primary example was set with Frank Sr., who encouraged his sons, Jack and the late Frank Jr. — and their first cousins, Jack and Joe Reilly — to join the profession.

“I took the job to pacify (my dad) when I was 18,” said 76-year-old Jack Reilly, who retired in 2003 after more than 42 years and who served as a passenger conductor for NJ Transit and a conductor for Erie Lackawanna.

“As I got older, it became my life,” the Mount Bethel resident added. “I understood the job. And I have friends for 50-some years because of it. The railroad was a great job. I enjoyed it and have no regrets.”

Long before his own retirement — and indeed his own start — Jack Reilly started the tradition of riding a family member’s final excursion when, while still in elementary school, he accompanied his father for his last run between Hoboken and Montclair, New Jersey. He repeated the task for his brother, Frank Jr., on his last run, and years later, his nephew — Frank’s eldest son, Pat — returned the favor.

Much to their mother Mary’s chagrin, all three of Frank Jr.’s sons held careers in the industry. (Only their sister, Mary Ellen, respected her wishes by becoming a teacher.)

“My mother wanted everyone to go to college because of the long hours (in railroading),” Pat Reilly said. “When my summer job in Hoboken lasted four years, a friend intervened and said to her, ‘There’s good money, and there’s worse things.’”

His brother, Mike, did in fact attend Lackawanna Junior College on a basketball scholarship for a year, but school did not feel like the right fit for him. When he climbed aboard the trains at age 20, he found the pay for being on-call to be better than what his peers were earning, and so he stayed on. An added perk, he noted, was the freedom of not having a boss looking over his shoulder every minute of his shift.

Still, Mary Reilly was determined to sway her last son from following in their footsteps.

“On my end, being the youngest, I was told I’d do something different,” said Brian Reilly, 50, little brother to Pat and Mike. “I worked in sales at a plastic company, and when Mike got me my job, my mother cried. At the time, I had no kids and was single, and I quickly fell in love with it. I loved the people. And coming after (my brothers and uncle) with the name, everybody knew who they were. I had an easier path than others.”

From 1994 to 2009, Brian Reilly worked for railroads including NJ Transit, and the Dunmore resident remains adjacent to the business in his current role as a human performance specialist for the Federal Railroad Administration.

Nepotism was considered a good thing by those outside the family, Pat Reilly pointed out, because if there was a problem with one Reilly, supervisors would go to another one to straighten him out. On the other hand, each successive Reilly was lucky to have had someone more experienced to look up to.

“We’re lucky we were hired out years ago, especially in a place like Scranton, and learned from the old-timers, because they were a wealth of knowledge,” Pat Reilly said. “We had time to just absorb.”

Submitted Photo

Mike Reilly Jr. marks his retirement from the railroad industry as he steps off an engine in Dover, N.J., on July 5, 2019.

Each of the Reillys dabbled in different positions, from caboose riders to supervisory roles, and all worked on both passenger and freight trains and with various companies.

“It’s been good to our family. It’s a family-securing job, which is hard to come by these days, but it’s a different lifestyle,” Brian Reilly said. “If not for the railroad, I might never have left Scranton. But I lived in California. I travel all over the country. I get to see some great places.”

Working on trains instilled certain characteristics in the Reillys. They’re all sticklers for punctuality. They have little patience for slacking off on the job (“There’s no way to fake the work ethic. It’s easy to spot people who don’t do the work,” Brian Reilly said). And they all have a great awareness and appreciation for personal safety, especially after catastrophic experiences aboard trains.

In his career, Jack Reilly lived through derailments, including one with a coal train that tipped over so far when extreme heat bent the tracks, that by the time the engine stopped, he could reach out a window and touch dirt. He also has been around with seven deaths, including a man who looked into his eyes just before purposely stepping into the path of train moving at 70 mph to kill himself just before Christmas.

“At the end of my career, I was mentor to young guys, and I would tell them, ‘We don’t use Band-Aids, we use body bags,’ ” he recalled.

Pat Reilly still occasionally serves as a consultant in investigating accidents, and he was part of a team that handled a double fatality in Florida when a train hit a school bus, which resulted in additional safety legislation in 32 states to prevent another such tragedy with kids.

But the positive memories of careers on the rails outshine the difficult ones. Each of the Reillys acknowledged a brotherhood with his colleagues that extended well beyond the familial bloodline. It’s a camaraderie they’ve all held on to, even after their lives moved off the tracks, so to say, and a bond so strong that retirements were emotional and difficult.

“In my experience, people really had your back,” Brian Reilly said. “And for me, it’s my family. We get together, and it’s what we talk about.”

“I’m proud to say Reillys always had a good name in railroading,” his brother Pat said, adding that he believes he knows how his late father would have felt about his sons carrying on the line of work.

“At first, he wouldn’t have liked it, but at the end, seeing all we did, he’d be proud,” he said.

Meet the Reillys

- The family traditions of railroading began with Frank Sr., who joined the industry in the mid- to late-1920s.

- His sons, Jack and Frank Jr., and nephews, Jack and Joe, followed in his footsteps.

- Frank Jr.’s three sons, Pat, Mike and Brian Reilly, became the third generation of railroaders when they all took on careers aboard trains, too.

Patrice Wilding is a 13-year employee of the Lifestyles Dept. at The Times-Tribune, where she worked her way up from a clerk to a web video producer to a full-time reporter, writer and copy editor. An Olyphant native, she graduated from Mid Valley Secondary Center and earned a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies with concentration in media arts, political science and communications from Wesley College, Dover, Delaware. She lives in Clarks Summit with her husband, Justin, and their son, Johnny. Contact: pwilding@timesshamrock.com; 570-348-9100 x5369; @pwildingTT