BY KENNETH TURAN, LOS ANGELES TIMES

BY KENNETH TURAN, LOS ANGELES TIMES

Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman” sounds like more of the same from a director we know well, someone we’ve been on a cinematic journey with for our entire viewing lives.

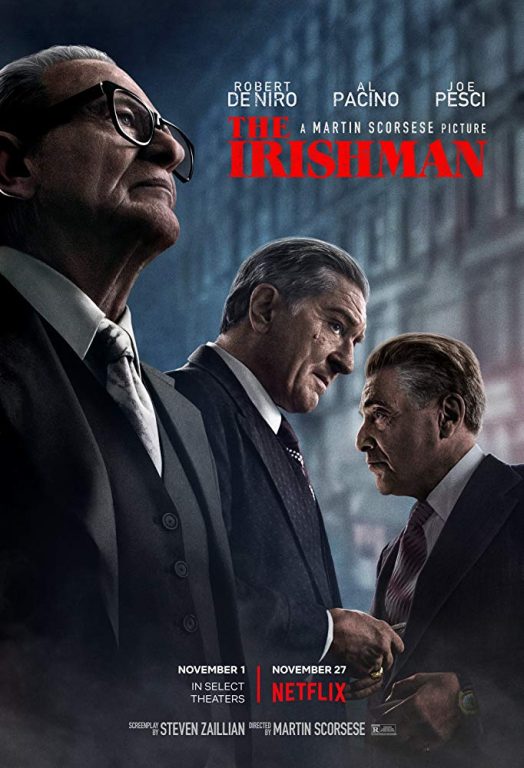

Yes, at 3 1/2 hours, it’s arguably longer than it needs to be. Yes, its possibly true story of the life and crimes of a Mafia hit man who claimed he killed labor leader Jimmy Hoffa has been called not credible and worse. And yes, it’s the umpteenth revisiting of the Italian American organized-crime milieu starring actors Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci, all directed by a man who also has been there before.

But, astonishingly, instead of business as usual, “The Irishman” is a revelation, as intoxicating a film as the year has seen, allowing Scorsese to use his expected mastery of all elements of filmmaking to ends we did not see coming.

Instead of the high-energy, borderline celebratory atmosphere that clung to films like “Goodfellas” and “Casino,” this is an elegiac, brooding gangster film that casts a mournful spell, that intentionally drains its gangland doings of glamour just as Rodrigo Prieto’s exceptional cinematography gradually drains the color out of its look.

A Mafia story that has more in common tonally with Scorsese’s “The Age of Innocence” than his “Gangs of New York,” “Irishman” brings to mind another late-career classic, John Ford’s “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence,” where the great director of westerns used icons he created to undermine a mythology he’d brought into being.

“When you get to my age,” the 76-year-old Scorsese said in a DGA Quarterly conversation, “you get a little slower, a little more contemplative and meditative,” and this turns out to be all to the good.

Rather than highlight the high life, “Irishman” focuses on regrets, on the confusion and even despair of a man near the end of his days trying to make sense of how he ended up where he did, trying to understand how he betrayed the people he cared about, all set against a broader tapestry of the dark side of 20th century American history.

The story of that man, Frank Sheeran (De Niro), the rare Irishman in La Cosa Nostra’s employ, and his relationship with the mentors in his life, Mafia don Russell Bufalino (Pesci) and International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Hoffa (Pacino), wouldn’t be the film it is without the master class in nuanced acting that trio provides.

While De Niro and Pacino movingly build on what they’ve done before, Pesci, previously a study in manic behavior, is especially impressive because he strikes out in an unexpected direction as an understated man who demonstrates he’s in charge by never raising his voice.

Because these actors have to play characters who start out decades younger than their chronological ages, “The Irishman” benefits from expensive computer-generated de-aging as well as the help of a movement analyst who reminded them how younger people move.

As good as this trio is, an equal strength of “The Irishman” is how well it’s acted across the board in a story so wide-ranging it lists more than 160 roles.

Casting director Ellen Lewis has filled each part with precision and care, using both expected players like Harvey Keitel, Ray Romano and Bobby Cannavale (all especially good) and people new to the gangland universe, like Anna Paquin in the key role of one of Sheeran’s daughters who becomes the film’s moral center.

Another key weapon in “The Irishman’s” arsenal is Oscar-winning screenwriter Steven Zaillian, who brings both gravity and essential humanity to this violent saga.

More than that, Zaillian effectively orchestrates an extensive alternate American history that posits mob involvement in everything from John F. Kennedy’s election to the bankrolling of Las Vegas.

Zaillian has crafted a script with real feeling for the allusive, almost blank-verse quality of crimeland dialogue, the unconscious Zen poetry of wise guys saying things like “tell him it is what it is” and “it says what it says.”

Working from Charles Brandt’s book “I Heard You Paint Houses” (apparently gangland slang for being a hit man), Zaillian came up with an intricate, three-level structure to the film.

It starts with a dazzling tracking shot (eerily similar to the celebrated one in “Goodfellas”) that prowls like Nemesis not through the exotic Copacabana nightclub but a pedestrian assisted-living facility.

Its quarry in the film’s 2002 starting point is Sheeran, with the then-82-year-old sitting in a wheelchair and talking about his past to an unseen interrogator, or maybe even to himself.

This triggers two different strands of flashbacks: an expansive one about the entirety of Sheeran’s mobbed-up career, working first for Russell Bufalino and then for Jimmy Hoffa, and a more focused reflection on what went down in the day’s leading up to and including the disappearance and death of Hoffa on July 30, 1982.

As “The Irishman” toggles among these three elements, it becomes completely involving without being in any kind of a rush. Masterfully edited as per usual by Thelma Schoonmaker, it is, like “Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood,” somewhat anecdotal in nature, but the surpassing skills and artistry Scorsese and his veteran team have accumulated over half a century of filmmaking pull us in and hold us absolutely despite the film’s unusual length.

Like many earlier Scorsese films, gangland murders are a major theme of the set-pieces, but even the re-creations of celebrated Mafia hits like the deaths of Albert Anastasia and Joey Gallo are treated matter-of-factly, like they are no big deal.

In the same vein is a fascinating technique the filmmakers have come up with to further deglamorize the proceedings. Probably a dozen times after a key mob figure is introduced, the frame will freeze and text will pop up onscreen precisely detailing how he died: “shot three times in an alley,” “nail bomb under his porch,” “shot eight times in the head in a parking lot.” An enviable way of life this is not.

Because of the cost of the essential de-aging technology, the budget of “The Irishman” went well north of $150 million, which proved too rich for Hollywood’s blood. Netflix ended up picking up the tab, which, perhaps fittingly, created a melancholy situation of its own.

The streaming giant is owed enormous thanks for stepping up and making a work so unforgettable, but it is sad that, after only a month in theaters, this landmark film — a tribute to the unrivaled power of the theatrical experience — will go to smaller screens so much earlier than it otherwise would. The old order changeth, yielding place to the new, but that is not necessarily the best of news.

‘The Irishman’

- Rating: R, for pervasive language and strong violence

- Running time: 3 hours, 30 minutes