BY CHRISTOPHER BORRELLI, CHICAGO TRIBUNE

A perfect gift book is not for reading. Not now. You don’t want to give someone a book, watch them flip through monochromatic text, put it aside with a flat smile then promise to let you know what they think — five days, six months, nine years, from now? Do this right and they’ll curl into the pages, blocking you out immediately. Which isn’t to say avoid giving book books this holiday — books that tell stories, rely on literature, letters and sentences — but rather, a perfect gift book offers a bit more, a personal connection, a history, a quirk, a tasteful box biding together a complete something or other, or just a shape or size so unusual the person receiving the gift has no choice but to bond with it.

This needn’t get expensive.

A couple of times I’ve given my daughter a book from British publisher Folio Society, which offers some affordable keepsakes of classics like “Anne of Green Gables” (in the $50-ish range). She can’t read yet but she stares at the illustrations (created exclusively for Folio editions), and my hope is she owns these books for generations, carrying them through life. Which is the trajectory of the perfect gift book — it sinks into someone’s personal woodwork. But to achieve this, you need to pair the right book to the right person. That’s the tough part.

To help, what follows are some favorite recent gift books, paired to an ideal recipient:

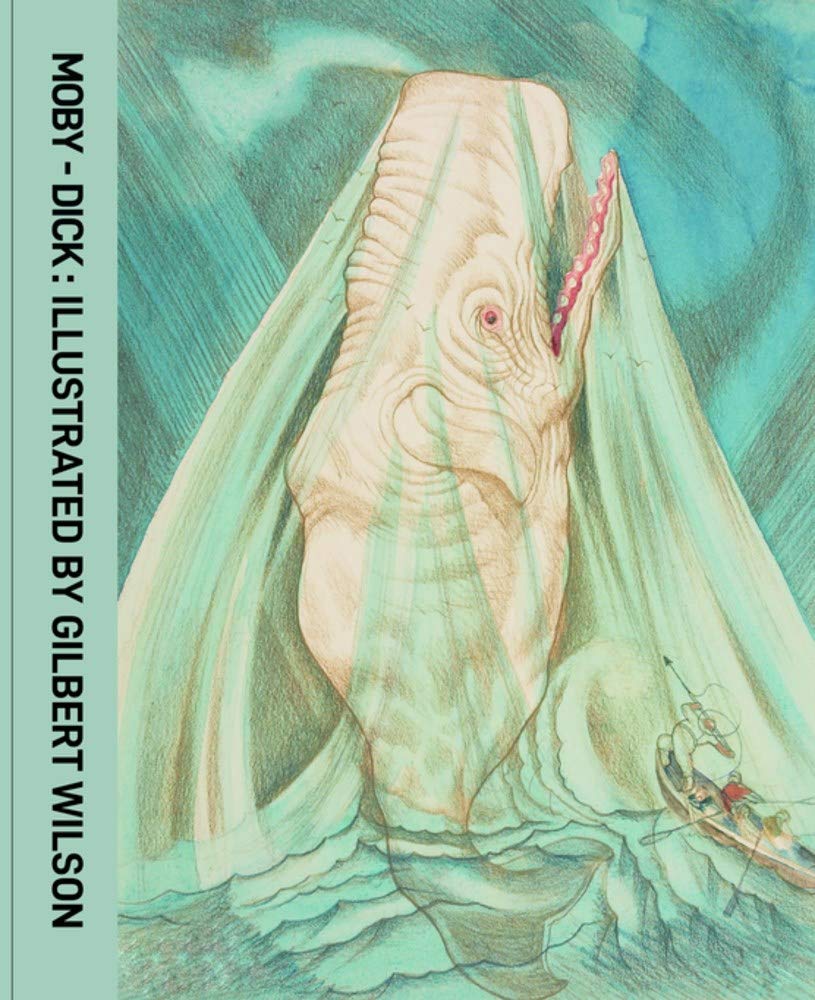

For the Cousin Who Swears She’ll Read Moby-Dick This Year: “Moby-Dick: Illustrated by Gilbert Wilson” ($60, Hat & Beard). A largely forgotten Indiana painter (best remembered for his Indiana University murals), Wilson was never satisfied with Rockwell Kent’s woodcuts of Melville’s classic. So, as shown in these obsessive pages, he spent a lifetime re-imagining the book, planning an opera, even working on the 1956 John Huston adaptation. Most of that work would remain personal and became obscure. But this book, filled with Wilson’s haunted Diego Rivera-like illustrations (and lots of white space, perfect for the 19th century-literature adverse), is a generous corrective.

HAT & BEARD PRESS / TNS

“Moby-Dick: Illustrated” by Gilbert Wilson

For the Friend Who Really Needs to Stop Checking Instagram: “Ballerina Project” ($40, Chronicle) traces 25 years (some on— Instagram, where it’s a must-follow) of grace and inspiration from Dane Shitagi, who has been photographing ballerinas against backdrops like city beaches and machine shops and subway stations. The book doesn’t offer much beyond the images themselves, but is consistently lovely.

For the Literary-Minded Movie Aficionado: This slender, pocket-sized edition of Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning screenplay for “Get Out” ($19.95, Inventory Press) has 15 pages of his annotated thoughts on scene after scene, including the script of an alt-ending. Putting it in context, an excellent essay from black-horror historian Tananarive Due. More unexpectedly revealing: “The Hollywood Book Club: Reading With the Stars” ($16.95, Chronicle), about 100 pages of images of movie stars just reading. Some of the portraits are promotional (Gregory Peck reading “To Kill a Mockingbird”) but then there’s actors breaking up on-set tedium with a good book, Sammy Davis Jr. at poolside with a paperback, James Dean at an Indiana kitchen table reading poetry.

For the Contemporary Art Monster With an Eye on History: Performance art is notoriously hard to pin down, yet “member: Pope.L: 1978-2001” ($40, MoMA), the catalog for a new retrospective of William Pope.L at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, makes a furious, unsettling case that a book of interviews and essays might do the trick. The University of Chicago associate professor has crawled for blocks, buried his body in holes and generally provoked (the book itself has a small physical hole at its center), all laid bare with unexpected clarity. On the cover of “Great Women Artists” ($59.95, Phaidon), “Women” is crossed out, a nod to the dueling need to both celebrate female artists and erase labels. It’s an addicting resource of a doorstop. The weight is on artists from the recent past, but then, the fact that this is a fairly thorough survey of important women artists (dating back centuries, allowing each a big piece of art and critical profile) and the whole thing runs 445 pages, provides its own critique.

For the Architecture Junkie Sick of Hearing About Frank Lloyd Wright: “Midwest Architecture Journeys” ($40, Belt) is the ho-hum title for this vibrant, funny and consistently interesting road trip through the built environment of the Midwest. Yes, you get Louis Sullivan — but mostly Louis Sullivan in central Ohio — along with essays (from assorted critics, historians and journalists) on the Hobbit-like homes of Lake Michigan, the legacy of Midwest Futurism, an appreciation of grain silos, the parking lots of Flint. (Unlike a lot of coffee table books, you will actually find yourself reading this.)

For the Melancholy Time Traveler: “Holiday: The Best Travel Magazine That Ever Was” (Rizzoli, $85) — full of socialites, periodicals and midcentury intellectuals — can feel like an elegy for a lost America, the magazine business itself, the days of public smoking. It’s also a salute to a magazine that, in the decades after World War II, implored Americans to see the world not as full of experiences. It landed Joan Didion and E.B. White, photographers Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. It covered the exotic voyage and staycation alike. This giant engrossing book doubles nearly as a portrait of a nation discovering itself. The same is largely true of “Midcentury Memories: The Anonymous Project” (Taschen, $60) , which takes candid, amateur photos of everyday life from the postwar era and, without identifying places or names (hence the title), delivers a cradle-to-the-grave study of ordinary (albeit mostly white) people, as seen at backyard pools, on prom night, watching TV and attending funerals.

For the Fashion Philosopher: The large catalog for the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago’s recent blockbuster “Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech” ($65, MCA) can look at times as if it’s as much of a put-on as the show was itself. We get a “prototype” of an IKEA-receipt rug from the Chicago artist and fashion designer (really a picture of an IKEA receipt), then a comically thorough cataloging of all the hard drives (and digital files) that Abloh turned over for the MCA to draw from. But it’s also a portrait of an artist (like Kanye West, his longtime collaborator) seeing potential everywhere. Which was Bill Cunningham’s whole deal. The photographer, whose decades of shooting often prosaic street fashions for the New York Times gets a rich history in “Bill Cunningham on the Street: Five Decades of Iconic Photography” ($65, Potter) . There’s lots of chuckles — down-filled quilted evening wear, commuters stepping into knee-high puddles — but the larger mission of enshrining every trend and micro-trend (while simultaneously reminding us of the inward-looking lonesomeness of his subjects) receives its due.

For the New Yorker Subscriber Needing to Toss Out Some Old Issues: “The Lives of the Artists: Collected Profiles” ($125, Phaidon) blows past the typical updating of old editions. In this case, art critic Calvin Tomkins’ 2008 collection of art-world profiles is expanded from its original 10 pieces to more than 80, then spread across six volumes and held in a box. It lacks visuals (entirely), but as a study of longtime critic (Tomkins is now in his 90s, and the most recent piece here was published this year), it’s unmatched.

For the Wiki-Phobic: As you might expect from a title like “The Newish Jewish Encyclopedia: From Abraham to Zabar’s and Everything in Between” ($36, Artisan), there’s little here that’s orthodox. Which doesn’t mean it’s slight. Vera Nabokov gets her own entry, but then so does Alicia Silverstone. Bagels are described as “one of the moss controversial Ashkenazi American foods”; while Barbra Streisand is the “most famous, powerful and influential Jewish Woman to have ever lived, including every woman mentioned in the Bible.” There’s a cultural explanation for the difference between interrupting and “cooperative overlapping,” and an argument for Mr. Spock as the most Jewish of “Star Trek” characters. It’s all fun, often heady stuff.

For the Aspiring Literary Hoarder: It’s not hard to find books on books, but like any self-reflective medium, it’s harder to find preaching that carries beyond the chorus. Remarkably, “The Lost Books of Jane Austen” ($35, Johns Hopkins) by Janine Barchas — a University of Texas English professor and Austen scholar — finds something fresh to say about the exhaustedly-mined author. It’s a visual study of Austen’s publishing history that, in many ways, provides a wider history of how early popular novels traveled across borders and class. (Among the finds, exclusive hotel editions of “Pride and Prejudice,” used unceremoniously as a coaster.) A few of those covers appear in “The Penguin Classics Book” ($40, Penguin), a country-by-country, decade-by-decade look at the covers of that venerable paperback publishing line. Many more are found in “Biblio-Style: How We Live At Home With Books” ($35, Potter), which is frankly book porn — but of the nicest kind, a guilt-free peek at personal libraries of authors, collectors and booksellers that range from cluttered to even more cluttered.

For the Serious Pop-Culture Archivist: “Marvel: The Golden Age 1939-1949” ($225, Folio) is a splurge of a gift, and only for the devoted. Not a history of the publisher, not a tie-in to the movies. This is the comics — coffee-table size reproductions of 1940s appearances of Captain American and pals. Marvel was Timely then; the art and writing is notches below here it stands today. But this is the DNA of our current superhero obsessions, lovingly reproduced. Similarly, despite the title, “It’s Garry Shandling’s Book” ($40, Random House) is not the thing itself. It’s not a lost autobiography or even the biography the comedian will eventually receive. (Its author, filmmaker Judd Apatow, already made a masterful four-hour-plus Shandling documentary.) This is an archive dump, and a moving one. There’s testimonials from his funeral; Post-Its of encouragement he wrote to himself; a thank-you letter to George Carlin; and the text of his very first joke: “I was born in Chicago, Illinois. Then when I was two years old, my parents moved to Arizona — I wish they would have told me.”