PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

“I Am C-3PO: The Inside Story” by Anthony Daniels

BY CHRISTOPHER BORRELLI, CHICAGO TRIBUNE

RESTON, Va. — This place, all sterile office complexes and managed greens, looks like it was built yesterday. To be exact, it was built in 1964, but that sounds ancient. “A little cold around here, if you ask me,” said Anthony Daniels, who has spent most of life as a robot. He was here a few weeks ago for a small film festival that was giving him an award; he was here because he has played C-3PO, the fussy gold droid of “Star Wars” fame, for more than 40 years, and being a “Star Wars” character carries a responsibility.

So he marches in a parade to the festival’s opening-night screening of the first “Star Wars” film, flanked by Stormtroopers, a Kylo, a Darth, a Boba, a few Imperials and some Jedi. There’s a healthy turn-out, but on a Thursday afternoon, far from a crush of fans. He holds a plastered expression of delight, though he’s seen it before — many times before.

He lingers outside the theater for half an hour, taking pictures and signing autographs, complimenting costumes and leaving every fan with a bit of his bottled-up alter-ego. A middle-aged woman approaches and she grabs his hands and recounts the way her troubled brother once wanted his “Star Wars” action figures arranged on their family’s living-room mantle just so, making sure C-3PO stood at the center. And then she sobs.

“It’s OK,” Daniels says softly, “it’s a lovely story.”

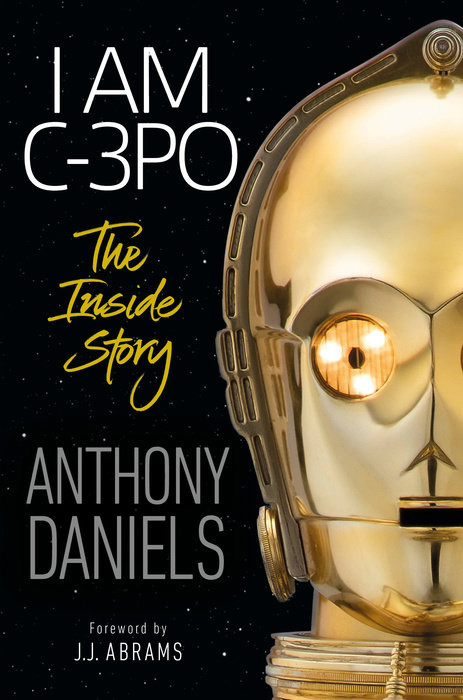

Tearful fans have happened before, too. And yet he’s here because of the award (a lifetime achievement from the Washington West Film Festival), and because he has a new memoir to promote, “I Am C-3PO: The Inside Story,” and because for decades Daniels has been a one-man ambassador for a franchise so ingrained in our cultural DNA, it only makes sense to call it a franchise if we also call the Grimms’ Fairy Tales a franchise. Daniels opens “Star Wars” exhibitions and speaks at conventions, MCs “Star Wars” concerts and product unveilings. In fact, since the 1977 original, only Daniels has been inside the C-3PO costume and voiced the character — and not only in the movies, but in the animated series, on “Donnie & Marie,” at the Oscars, on “Sesame Street,” for video games, anti-smoking PSAs, Underoos commercials, amusement park rides. “One reason people employ me (as C-3PO) is not only because I can perform the character, but I know what is right for him. In that way, he is as real as the last time you saw him.”

It’s a remarkable, and largely unsung, feat of performance: Though Daniels didn’t create C-3PO — that would be George Lucas — one man, and just one, who is now 73, has remained the steward and literal embodiment of the role he originated when he was 30.

Which can mean many things. At this festival, it meant a touch of quality control. He was introducing “Star Wars,” but even that simple introduction, of a film he’s seen countless times, its dialogue drilled into its brain, meant that Daniels paced backstage beforehand, writing, rewriting and memorizing a few lines many others would have simply winged by now.

And that night, when C-3PO strode across the screen and Daniels watched himself for the six billionth time and light danced on his face, he didn’t resemble an actor in love with himself. His expression was full of puzzlement and wonder, as if he was being reminded once again that he is part of something very dear to many people and he should not take a moment like this, even at a small film festival in Virginia, for granted. It is, after all, a complicated thing, to have your character recognized instantly, across the globe daily, for several generations, while being mostly unseen and unknown yourself.

The next morning, with a dollop of C-3PO’s familiar complaining in his English voice, Daniels mentioned to me that J.J. Abrams, the director of the next “Star Wars” film, “The Rise of Skywalker,” had been texting him incessantly, asking him to use his iPhone and voice a few lines. The film opens on Dec. 20, but the tweaking continues.

Daniels groaned playfully: “He’s driving me nuts! He’s just like ‘Can you do this line?’ Sometimes it’s other lines. I said, I’m busy, I’ll do it tomorrow. Then he goes into a sulk!”

Daniels looks and sounds a lot like C-3PO, sort of the way that dog owners and their dogs often merge: He’s trim, prim and nicely postured, with a crisp London accent, his words are exacting and his movements come across in a slightly haltering, self-conscious manner. The man is a human madeleine cookie. He is a Proustian manifestation of any “Star Wars”-filled childhood. When I mention we spent a few hours together in 2009, while he was in Chicago hosting “Star Wars: In Concert” at the United Center, he says, “I’d forgotten, I’d forgotten,” and what floods back at that moment is this: I’m seven years old, sitting in a movie theater, watching the first “Star Wars” for the ninth time and C-3PO is on the Death Star, remembering he has a transmitter to call Luke, saying in these same tones: “I’d forgotten, I’d forgotten.”

“You know, while I’m doing 3PO in a new film,” Daniels said. “I do begin to sound and behave like him. I notice I can get jerky, and a bit precise — I have to try and watch it.”

He didn’t always feel that fondness.

Indeed, that affection awoke only recently, about a decade ago, after 30 years with Lucasfilm. His memoir begins with the “Star Wars: In Concert” tour that took him through Chicago, which he says was the first time he truly understood the devotion to the series: Night after night, he looked out into sold-out arenas and watched the faces, and “they got something I never got. You could feel warmth, affection, energy. I began to recognize they collectively owned something that I didn’t own. I was in it, but I didn’t own it, and that really warmed me toward this whole thing. Sir Alec Guinness (who played Obi-Wan Kenobi and famously held a long ambivalence about his role in “Star Wars”) never had the opportunity to get to that state of acquiescence. And he really had done other stuff!”

Daniels, however, maintained a long simmering animosity to the series, “because of my original dismissal, if you will. It had been a slap in the face that took many years to disappear.”

This “dismissal,” which forms the sometimes lonesome spine of the book, is less a formal rejection than a suspicion that Daniels had felt in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, when the “Star Wars” Industrial Complex was first humming along and devouring pop culture. Because he was essentially faceless, because his body was hidden behind a mask and a gold robot costume, he believed that he was being written out of the glory bestowed on the series. He believed that he had been made a literal cog in the machinery of a cultural phenomenon.

That hurt, “it’s still there,” he told me, “but it’s since been colored by other things that have made all of this nicer.” Then he added with a smile, “If you work for 20 years at Lucasfilm you get an award, and it’s a gold R2 and 3PO or something. I think 3PO is clutching a tub of popcorn. I’ve worked there on and off for more than 40 years — nada.”

“I Am C-3PO” is not exactly a tell-all — indeed, “Star Wars” fans won’t find a lot of new stuff here — but rather, it’s much more interesting, select notes from the margins of a cultural happening, as told by a man submerged inside a sweaty, stiff uncomfortable robot, with his nose running. On Kenny Baker, the actor who was occasionally inside the R2-D2 suit (and died in 2016), Daniels writes coolly: “He appeared at countless conventions and the fans loved him. Sadly, our off-screen history prevented me from feeling the same.” He recounts Lucas hating his initial performance (“Well, I … err … never thought of Threepio being a British butler”) and he recalls the production of the maligned prequels as bullying, inconsiderate and “industrial,” with “a sense of an oppressive management ethos coming from above.”

Daniels writes (without a ghost writer, he noted) about what it was like being devoured, more or less, by C-3PO, though not always unpleasantly. The book is somewhat about how an actor develops an intense ownership over a character. Daniels carries a gold Sharpie for autographs. He describes a “Star Wars” art exhibition where he noticed the C-3PO costume was missing pieces around his connecting joints, and so, Daniels scrounged up some wires, and when no one was watching, unhooked the glass case and added the wires to the gaps in the costume and spruced up the display.

Daniels was one of the first actors cast for the original “Star Wars,” in 1975. He was primarily a stage actor, skilled in the “isolation techniques” of mime; by coincidence, when Lucas hired him, he was playing Guildenstern in Tom Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” another peripheral figure at the margins of a larger epic.

“But without ‘Star Wars,’ without 3PO, I would have had a completely different life,” he said. “I am only now beginning to admit in public, I was a very mediocre actor. Average, to say the least. Wanting to act is not the same thing as being good, and I lucked out.”

And yet, I said, in a way, it’s a role that transcends traditional acting. Whether he was a good or a bad C-3PO hardly matters. He was C-3PO, he gave the droid a reality, end of argument.

He said this is probably true, that “it occurs to me maybe 3PO was my refuge, from being negated in other ways.” So, naturally, over the years, he became a student of, and often friends with, other actors who had spent similar careers submerged inside of an unusual artifice. People like the Australian comedian Barry Humphries, who at 85 remains inseparable from his boisterous housewife/journalist/talk show host Dame Edna; and the puppeteer Caroll Spinney, who stood inside of the Big Bird costume from 1969 until his retirement last year. (Comparably, Chewbacca has been played by two different actors, Peter Mayhew, who died in April at 74, and now, the young Finnish actor and basketball player Joonas Suotamo.)

Acting entirely inside a robot was so confusing at first that, on the set of the first “Star Wars” film, as a somewhat light-hearted reminder, Daniels handed out matchbooks to the cast and crew that reminded them “3PO is Human!” He said it wasn’t about insecurity, “but on a set people get on with their jobs and when you’re standing in the middle of everything (in the C-3PO suit) and people are walking around you,” it’s natural to develop a tinge of unease.

Decades later, after a string of recent “Star Wars” movies in which his character was played more as ornamental nostalgia than a character, he said C-3PO “is there with the gang again” in the upcoming “Rise of Skywalker.” Asked if he was surprised when C-3PO became the tear-jerker centerpiece of the film’s popular trailer — saying he was looking at his friends “one last time” — Daniels looks wistful. “Oh, yes,” he said, “a trailer can pick out anything it wants and that’s one of the seminal scenes (in the film). What I love was it was (shown) exactly as it was done. … It was a touching moment on the set, despite all the clutter around.”

He says, at 73, “there are not that many years left” for him to do the character. He doesn’t want C-3PO “shoved into (any proposed future installments) as a figurine,” but then he adds the ageless C-3PO is pretty good as connecting tissue between the original films and a new series, “so I would be there to do it — I think his days in the offshoots are far from over.”

In the meantime, after decades of C-3PO cereal and PEZ dispensers and soap bars, he is only now finally receiving a small percentage of the sales of any C-3PO-related merchandise.

Like, what, .000002 percent?

“How many 0\u2032s is that?” he asked.

Unlike a Mark Hamill or Harrison Ford, it’s not Daniel’s actual likeness on those action figures and bedsheets, it’s C-3PO’s likeness. So what he receives now “feels more like a gesture — but at least they recognize I have some part in people buying this item. I sort of minded I wasn’t given anything (in the earlier days of the series), but that was par for the course. Now it doesn’t really make a difference. I’m comfortable. My wife and I lead a very modest life. I don’t have to keep up with anybody. We own two tiny cars. We don’t collect anything, I don’t enjoy buying clothes. I wear a watch that costs 25 quid. And as long as I have comfort and warmth and can travel on the nice part of an airplane I can’t think of anything else I need. But there are times, when negotiating a fee for something, when a producer or someone may say to me, ‘Anthony, it’s only a one-day job,’ or ‘It’s just five minutes.’ To which I say, ‘Well, in those five minutes, you’re paying for 40 years of C-3PO.’”